Clique aqui para Português

The Lagoa-Barra Expressway separates the favela of Rocinha, located in Rio de Janeiro’s South Zone, from the adjacent, wealthy neighborhood of São Conrado. The noisy two-lane motorway begins in the Miami-like Barra da Tijuca strip, running through São Conrado, alongside Rocinha, and eventually underneath Rocinha’s hillside in the Zuzu Angel tunnel before popping out into the neighborhood of Gávea. Also known as the Autostrada Engenheiro Fernando Mac Dowell, the motorway’s 1971 construction was fundamental to many other contemporary developments in the area, including sidewalks, new buildings, and the current waterfront area. But while it drove demographic and economic growth in Barra da Tijuca and São Conrado, it also became a physical barrier, preventing Rocinha residents from entering the two affluent bairros: a border separating the favelas from the rich.

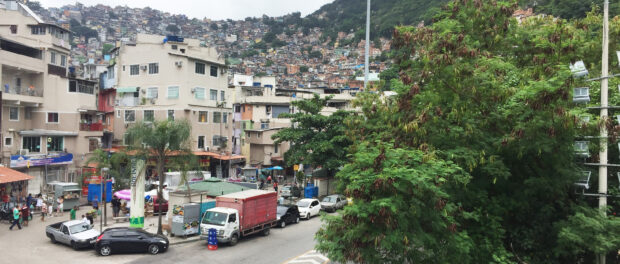

Living on the southwest side of the road—the São Conrado side—means having access to better infrastructure, sanitation, and opportunities. It means having a yearly income almost 12 times higher than that of the residents of Rocinha, a 5-minute walk away. It means living in tall residential buildings overlooking the ocean, as opposed to the irregular texture of low-brick houses that cover the morro. Much as São Conrado and Rocinha residents share a metro station (tellingly named “São Conrado”) exiting on the São Conrado side means walking some of the most expensive streets in all of Rio de Janeiro: the neighborhood even has its own shopping mall and golf club. Residents of the Rocinha side lack access to basic sanitation and facilities.

The Lagoa-Barra expressway is an example of an urban barrier: an obstacle that prevents easy movement and defines two separate spaces. Though in urban studies, the term “urban barrier” may refer to different types of physical barriers found in urban environments or that are part of urban life, they share the characteristic of limiting access to part of a city for a given group of residents. In her article Planning the City Against Barriers: Enhancing the Role of Public Spaces, architect and professor Aleksandra Sas-Bojarska of Gdansk University of Technology writes that our “contemporary cities are being fragmented by a growing number of technical barriers like roads, railways, infrastructural objects, that generate a variety of problems of different nature.” Among those problems, there are functional disadvantages, inequality in accessing the same opportunities that cities offer, and minority segregation. In this way, urban barriers contain and define social inequality. They separate people. As a result, residents can have completely different experiences of the same city.

The OECD study Divided Cities: Understanding Intra-Urban Inequalities shows that spatial segregation and physical barriers contribute to perpetuating existing social and economic inequality. For example, those who live in neighborhoods disconnected from public transportation tend to have lower incomes because they have more limited access to job opportunities compared to residents of more connected neighborhoods. The study, undertaken by the OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities’ Paolo Veneri, demonstrates a clear and positive association between income segregation and city characteristics such as size, income level, and urban planning. In fact, how cities are built and structured influences residents’ access to other people, common resources, and other important features of the city. According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: “urban environments, infrastructures, facilities and services can impede or enable, perpetuating exclusion or fostering participation and inclusion of all members of society.”

In Rio de Janeiro, urban barriers are a central aspect of city life. Lower- and upper-class neighborhoods reside jarringly close to each other and yet remain entirely separated. Despite Rocinha’s extreme proximity to the two affluent neighborhoods of Gávea and São Conrado, residents are keenly aware of the presence of boundaries: they often say that people live “inside” or “outside” the favela as if a real border divided them from the rest of Rio.

City planning and urban interventions can be precious tools in overcoming physical as well as internalized barriers. They can also be testaments to existing inequalities and perpetuate the status quo. A pedestrian overpass has for decades been fundamental to connecting Rocinha and São Conrado, over the Lagoa-Barra Expressway. In 2010, the 60-meter passarela was upgraded with a design by the renowned Carioca architect Oscar Niemeyer, costing R$15 million (today US$3.2 million). The overpass connects the community to a sports center complex.

The curvy and majestic shape of the passarela is recognizable from afar, acting to some as an incisive symbol of integration, visually inviting passers-by to cross into the community. To others, however, it is a symbol of misused public resources. Rather than investing in critical services like sewerage in the favela, funds were used on the community’s edges to make passing by more bearable to those on the Lagoa-Barra Expressway, they argue.

The Niemeyer overpass was one of several upgrading projects that took place in Rocinha as part of the PAC (Growth Acceleration Program) program launched in 2007, which aimed to accelerate Brazil’s growth through investments in construction, sanitation, and transportation projects. Lauded early-on for its construction of public works in Rocinha and other favelas, the PAC drew criticism for ignoring more fundamental sewerage and infrastructure works before it was finally abandoned with changes to national leadership and as the country plunged into its post 2015 recession.

Other PAC public works purportedly intended to foster connectivity have floundered or drawn widespread criticism for their focus on high-visibility, tourist-friendly works. Now-defunct cable cars in the favelas of Morro da Providência and Complexo do Alemão stand as a testament to the woes of top-down city planning; residents fought tooth and nail against similar cable car plans for Rocinha.

To achieve an inclusive city, urban policy must commit to social integration as a fundamental tool for tackling Rio de Janeiro’s challenges, recognizing the power of favelas as part of the city’s development and not something to be walled off. Deconstructing urban barriers through urban design is fundamental to guaranteeing favela residents their right to the city, ensuring integration and equality.

Camilla Piccolo holds a Master’s Degree in Architecture and Landscape Architecture from Kingston University and a degree in Architecture and Architectural and Building Sciences/Technology from Politecnico di Milano.