This is our latest article on the new coronavirus as it impacts Rio de Janeiro’s favelas. It is also part of the debate promoted by RioOnWatch about media narratives and representations concerning favelas in Rio de Janeiro. After reading, if you’re interested in learning more, participate in our live debate, May 21, in Portuguese by signing up here.

Since March, the Covid-19 pandemic has generated a massive need for information and previously unheard-of production of news around the world. The spread of the disease, protective measures, emergency policies, critical situations in health systems, and the collateral damage of physical isolation are among just a few of the countless topics to covered.

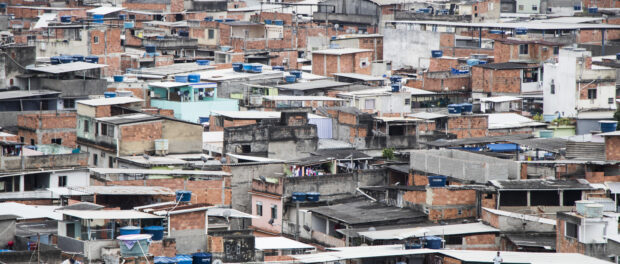

The arrival of the virus in Brazil’s favelas has in turn generated a great volume of articles covering the potential impact—sadly now a reality—of the disease in the peripheries of Brazil. Unfortunately, as is customary in coverage of favelas, even in the context of the pandemic, counterproductive coverage and problematic journalistic practices persist.

Although many stories have justly covered impending situations and community organizing efforts, emphasizing local solutions without perpetuating unjust stigmas, numerous others continue committing common mistakes of reporting on favelas. In this article, community journalists and international observers highlight seven mistakes being made by mainstream press covering Covid-19 in favelas, both in their narratives and in their journalistic practices, in the hopes of halting their reproduction.

1. Falling for the Same Old Mistake: Sensationalism

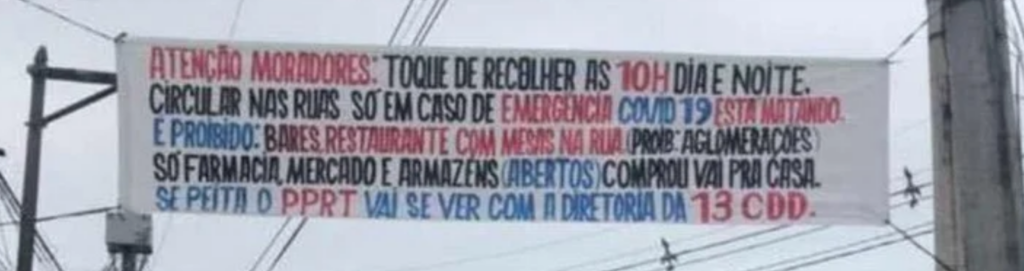

Violence in the favelas has long been the primary theme covered by mainstream media, crystallizing an already stigmatized image. Even the coronavirus crisis doesn’t seem to have discouraged certain channels from continuing to circulate the same sensationalist ideas, at times based on very little evidence. In particular, during the pandemic, and even while community organizations responded to the crisis with incredible readiness, several Brazilian and international media outlets decided to focus, in the third week of quarantine, on reports of drug traffickers imposing curfews in certain communities. This superficial news item served no social function, using up readers’ time and energy at a time when reading and sharing quality information was critical to saving lives. There is no ethical justification for this focus during such a critical week. Such negligence, as is commonly the case in coverage of favelas, is carelessly “justified” only by media outlets’ desires for clicks and profit.

Although it is a sad truth for some communities in Rio, the actions of armed civil groups (and it is important to note that there are far fewer reports of the same phenomenon in areas controlled by rogue police militias, including cases of militias preventing isolation measures), are a single element within a rich, complex, and much more important story: community mobilization in the face of State neglect. By casting a stigmatizing spotlight on such a minor element at a time when favela resilience and protagonism should be the primary story, the media’s bias when it comes to favelas is even further unmasked.

2. Romanticizing Confinement

In reporting about lifestyle adaptations in times of physical isolation, some journalists have focused on stories of those who have managed to deal with the situation well, without mentioning the difficulties experienced by the great majority of people. If some are making use of isolation to devote themselves to their families, rediscover simple pleasures, and take care of themselves, in reality, for many more in our society, the greatest concern during quarantine is that of surviving hunger, fear, promiscuity, domestic violence, and feelings of hopelessness.

This narrative of quarantine as quality time for reflection and a special moment to do things that are important to you is relayed by the middle- and upper-classes whose comfortable living conditions and concerns have nothing to do with those in the favelas. To romanticize confinement for these groups in turn, wherever they are, is to divert attention away from the urgent and fundamental needs we are experiencing as a society. If the pandemic is teaching us one thing, it is that everybody is intricately interconnected.

It isn’t a question of hiding that confinement can be a source of creativity for some and that there are many activities being developed to stay fit and look after one’s mental health despite social isolation, but reports should not create inappropriate narratives in praise of confinement.

3. Idolizing Community Organizers without Denouncing the Lack of Public Services

Since the onset of the Covid-19 crisis, many community groups have organized themselves to circulate information about preventing infection, collect donations, distribute hygiene kits and food packages to families in need, and more recently, sew masks, install community sinks and clean neighborhoods. These aid initiatives and organizing efforts, undertaken by and for the community, have become increasingly visible in the media, which is good for showing local agency and leadership and their efficacy and capacity, but not at the cost of failing to recall that a lack of public services and State negligence stands at the core of favela vulnerability. Community volunteers are forced to take the reigns because elected officials fail to fulfill their responsibilities.

In depicting these activists as heroes, the media normalizes and idealizes this transfer of responsibility. But the admiration is misplaced if it is not followed by demands for guarantees of rights, respect, and dignity. It diverts attention that should be focused on denouncing the lack of effective measures on the part of authorities rather than congratulating those who fill the void in as much as possible. The role of the media shouldn’t be to cast a complacent, even condescending, glance, but to show that these actions are no substitute for the State. We need both elements in articles about local initiatives: recognition of the fight, self-management, and resistance that favelas have built historically as well as recognition of the absence of rights that forces communities to organize themselves and forces community organizers to put themselves at risk on the front lines.

4. Not Covering, or Covering Superficially, Domestic Violence

Very little media coverage has examined the damaging social effects made worse by social isolation, such as episodes of domestic violence. Except for a few exceptions in the form of editorials in independent, thematic, or institutional publications, the production of contextualized and focused news specifically on this type of violence is rare or superficial. However, the disruptive impacts of this violence on the physical, sexual, reproductive, and mental health of women, children, and adolescents, including the LGBTQA+ population are immense and even more so now that running away is not an option.

The mainstream media began to echo the problem again only after an official declaration, in this case, that of António Guterres, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, who requested measures to combat the growing issue. However, the majority of coverage gave only a reproduction of Guterres’ words and the UN’s conclusions, with little thought to the internalized disruptions resulting from social isolation, such as anxiety, depression, suicidal thoughts, and aggression on the part of violent husbands and boyfriends. The coverage also lacks historical perspective on other moments of societal crisis that have impacted the economy and politics: epidemics have, historically, brought an increase in violence against women, as was the case with Ebola in Africa and cholera in Haiti. There are also very few articles that mention or analyze the existence of a mere 21 24-hour police stations specialized in protecting women in the whole country. Of these, only the state of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro have police stations outside their capitals.

Once again, the most common narratives reproduce the idea that the role of victims is always to protect themselves through various approaches, without placing enough blame on the aggressors. There are also very few articles intensifying the debate around the need for anti-sexist educational policies to counteract dominant attitudes and hold men responsible for taking the initiative in preventing violent acts at home in the context of the pandemic. There have been even fewer articles on the stress resulting from overloading women with domestic work and caring for family members who belong to high-risk groups.

5. Not Paying Favela Journalists for Contributions and Using People’s Images Without Permission

During the pandemic, even more so than usual, very few journalists have ventured into favelas. Their work, therefore, is largely based on local sources. Many residents end up carrying out the role of fixer or producing content that is used directly by the media. Despite the established partnership and the exchange of quality content, it is essential that services and teams from big communication networks, be it TV, print, or news outlets and agencies, pay for the support they receive and for the use of content produced by local communicators.

Even though relationships of exchange are fundamental at this time, due to economic questions of survival, the reproduction of content should start to be paid for by the big networks. It is also a way to help and support to the actions of communicators and favela journalists and their families. (Important: this guidance does not refer to interviews carried out with residents as sources of information.)

Just because we are in times of crisis, does not mean that the usual principles of journalism, like image rights, can break down. And yet, we have heard a number of reports of lack of professionalism and respect in this domain. For example, in March, a social project in City of God was contacted by two freelance photojournalists with the supposed intention of photographing families from the favela in order to help. But they weren’t clear about the real intentions of the photos, which ended up being sold to several different communication service providers, even appearing on the covers of two national newspapers and on TV. Those interviewed didn’t imagine that they would have their pictures exposed in this way. One pregnant woman who was interviewed was particularly affected, as many people judged and insulted her on the social media pages of the newspaper Extra. She felt violated and explained that she didn’t give permission for her picture to be used by all the outlets.

6. Lack of Investigation or Imprecise Information

When favelas are the subject, it is easy to find poorly researched articles in mainstream media, many of which contain insufficient information and even use fake images or data, as happened in a case in Acari. Quality research is necessary when it comes to subjects about the favelas, just as when information comes out about any other place, perhaps even more so. Having reliable sources is fundamental. It is necessary to look for local associations, residents, community leaders, journalists that live in the area, to access sites and social media networks and favela collectives, and, in this way, look for and collect quality information.

Moreover, it is fundamental that this information be accessible. It is of no use to want to inform favelas and then use words like “lockdown” or “home office.” Not just favela residents, but the majority of the Brazilian population doesn’t understand these terms. It is not enough for information to be disseminated, it must also be clear, direct, and accessible.

7. Lack of Empathy

Articles tallying favela deaths from coronavirus multiply every day, coldly pointing to each favela resident as just another statistic, when they should be celebrating the stories of these people, as is done for residents of affluent areas. It is fundamental to have a more human perspective, but without violating the privacy of victims and their families.

We recognize that getting this delicate balance right—combining empathy with rigor, without reproducing stigmas or romanticizing—is difficult, and that it is made even more difficult by the pandemic and the urgency demanded by major outlets. But the current crisis requires, more than ever, quality journalism.

This article was written collectively. It is signed by communicators Bia Carvalho, Carla Souza, Fábio Leon, Gracilene Firmino, Jota Marques, Tatiana Lima, Thábara Garcia, and Thaís Cavalcante.