This is our latest article on Covid-19 and its impacts on favelas and in the series of Teach-Ins on Covid-19 in favelas.

On April 20, Catalytic Communities (CatComm),* through its Sustainable Favela Network (SFN) and RioOnWatch projects, invited five community leaders and communicators—who are successfully confronting the Covid-19 pandemic in their favelas across Rio and São Paulo—to participate in an interactive live teach-in: ‘How to Talk about Coronavirus in Favelas?’ In total, 55 favela leaders and allies attended the Zoom session.

The special guests were: communicator Gizele Martins, representing the Maré Covid-19 Mobilization Front in Maré in the North Zone; environmental agent Geiza de Andrade from Vila Kennedy‘s Covid-19 Crisis Cabinet in the West Zone; communicator Rafael Oliveira of the Favela Vertical media collective in Gardênia Azul, West Zone; popular educator Ilaci Oliveira from the Transvida Cooperative waste-picker collective in Vila Cruzeiro, North Zone; and Gilson Rodrigues, president of the residents’ association of Paraisópolis in São Paulo and coordinator of the G10 Favelas organization.

The event was designed to address the difficulties and demands that have arisen among community organizers in the Sustainable Favela Network in their responses to the coronavirus crisis in their communities. The five speakers talked about strategies that are working in their favelas to provide information, communicate, and organize communities in the face of the pandemic.

The panel members all share deep experience in social work and local communication and were able to quickly adapt this knowledge and apply it to realize a community organizing strategy in response to Covid-19. Through the crisis, leaders in the areas of culture, communication, education, labor, and the environment, among others, have all redirected their priorities to focus on preventing and mitigating the impacts of Covid-19. In the absence of the State, as has been the case for so long, it is once again civil society in the favelas that is at the forefront of defending and guaranteeing people’s rights.

Shared Priorities: Inform, Collect Materials, Help

In the early days of the crisis, the priority was the same: to communicate and disseminate information to residents about the arrival of Covid-19 in Brazil and, consequently, in the favelas. In addition to communicating via community media, social networks, and WhatsApp, the speakers explained that to reach the entire local population, it was necessary to use cars with megaphones, informative banners in the street, and posters in local businesses.

During the teach-in, Gizele Martins—from the Maré Mobilization Front, established in early March in response to the crisis—said that for communication to be effective, one must use simple and direct messages. She explained that messages took the following forms: “The best hospitals that should be used are such-and-such. The number of dead and infected in the community is such-and-such. We recommend that anyone who can stay at home should stay at home. Stay at home, resident! Help your neighbor if you can. Collaborate with soap and water,” and she added: “In addition to prevention and hygiene, we also started talking about domestic violence, because we were seeing an increase due to people living in isolation.”

According to Martins, “the car with the megaphones was the most effective tool,” despite also being the most expensive communication strategy. The weekly cost is R$600 (US$103). Martins clarified that the decisions of the Maré Mobilization Front follow a very clear logic. “We decided to use this [form of] communication because we understand what works in our favela,” she said.

A few days after the first physical isolation measures were put in place, organizers identified the issue of food scarcity, which arose in part because of the new lack of daily income for many workers. Thus, organizers needed to concentrate efforts on supplying products to meet basic and urgent needs, such as water, food, and cooking gas. In addition, they needed to respond to the specific demands of the pandemic, such as propagating the use of masks and the installation of hygiene posts—with soap and water for people to wash their hands—in strategic locations in the community. Especially because there are homeless families living in areas surrounding Maré.

To finance the communication work and distribution of food baskets, many groups created online fundraising campaigns to raise money. At the same time, groups are also receiving physical donations, but it is a process that requires a high level of organization. Geiza de Andrade, from the Vila Kennedy Crisis Cabinet, explained: “We have a community center at the entrance where people who are afraid to enter the favela can leave donations outside, and from there we can distribute the donations to other sites.”

Ilaci Oliveira, from the Transvida Cooperative, which works with waste-pickers in Vila Cruzeiro, in Complexo da Penha, explains that despite their best efforts, the initiative has not been able to meet all the needs of the community. “We started to register people to receive food baskets… We have now registered over 1,800 families, but we haven’t been able to feed them yet.”

Oliveira went on to explain that the R$600 in government aid is not enough for many families. “They are saying: ‘It is not much. You know you can’t look after a family with R$600.’” Vila Cruzeiro has 70,000 residents. Martins also lamented the lack of resources for community communicators, and each and every one of the speakers at the teach-in expressed their concerns about their ability to fundraise, collect and distribute support to all families experiencing urgent needs over the long-term.

Decentralize to Reach More People

The Vila Kennedy Crisis Cabinet was created as a solidarity network, but now encompasses almost one hundred volunteers and partners. Geiza de Andrade is one of them. She highlighted how the work is organized in the community: “We divided Vila Kennedy as if it were a tic-tac-toe game, into nine pieces, with a leader for each part. That’s because inside Vila Kennedy there are several other smaller favelas.” Andrade explained that the community’s topography is another challenge. “There is a flat area and a hillside area, so we divided it into several areas to better cover the entire territory.”

Gilson Rodrigues, president of the residents’ association in the Paraisópolis favela, in São Paulo, and of the national G10 Favelas network, also shared pioneering strategies that have been very effective, garnering his community worldwide recognition. “For every 50 people, we have a volunteer resident who is the president of the street [block captain] and who coordinates 50 families. This person has some specific responsibilities: the first is to find a VP, because if they are absent, someone needs to replace them and organize everything in this process; the street president also helps to make people aware that they should stay at home, they monitor the 50 families through a WhatsApp group—with a particular focus on elderly and vulnerable people—so that an ambulance can be called when necessary,” said Rodrigues. The street president also distributes basic food baskets. “Those who are not at home do not receive a basket,” explained Rodrigues. It is a way to encourage adherence to isolation measures.

Supporting the Sick and the Unemployed

In addition to dividing up responsibilities in the community, the Paraisópolis Committee also organized to support families with people who are ill, for the most serious cases, and even in the event of death. They created two shelters for quarantining residents suspected of being infected with the coronavirus, but who cannot isolate themselves at home without infecting other family members. The shelters, which operate in two public schools, can house up to 260 people (with mild symptoms). The group also hired three ambulances with a 24-hour emergency team: two doctors, three nurses, and two first responders, who stay in the community and attend patients’ homes when necessary. “Because ambulances do not [typically] reach the favela, there is no fast support here,” said Rodrigues, adding that every day their ambulance is called into action.

The Paraisópolis Committee has even planned for how to remove bodies from the highest parts of the favela with minimal risk. “We are being very radical here in our preparation. As crazy as it sounds, these are things we have to think about. We are looking to organize ourselves for the worst.” Rodrigues stressed that the biggest difficulties are economic and that they also result from State neglect. “There are two distinct Brazils: the Brazil of alcohol in gel, the home office, the quarantine, and the Brazil that is going hungry, that is being left to its own devices, that is being ignored.”

The group has developed several methods to financially support parts of the population that are receiving no income, including a campaign called “Adopt A Housekeeper” (Adote Uma Diarista). The campaign registered 1,280 domestic workers who were laid off due to quarantine restrictions. The campaign managed to financially support 750 of the workers, with the rest receiving a hygiene kit and a basic food basket. Rodrigues has analyzed the possibility of extending this campaign to other professions. He stated that it is necessary to “think about how society can organize itself to support people with no income, because [if not] they will go hungry.”

Following the same logic of the favela taking care of its own residents, Rodrigues shared another initiative called the Home Office of Brazil’s Favela Seamstresses. The project distributes sewing machines to seamstresses who can then start generating income by producing masks. He states that “the project should produce more than a million masks in the next period to distribute in the favelas.” The Paraisópolis group also encourages the consumption of commercial products from within the community. “Instead of buying outside the community, we buy inside.”

In addition to being a local activist, Rodrigues is also coordinator at G10 Favelas, a block of social impact leaders and entrepreneurs from ten of Brazil’s largest favelas that have joined forces to fight for economic development and protagonism in favelas. “We have tried to reproduce what we do here [in Paraisópolis], in other parts of Brazil. To create our own public policies since there is no public policy for the country’s favelas,” explained Rodrigues, going on to conclude: “We have worked on a variety of solutions that can be adapted to local contexts.”

Obstacles: Government, Militias and Some Churches

The speakers also shared what obstacles are hindering awareness and aid work within favelas. Geiza de Andrade explained that in Vila Kennedy the influence of the president hindered the efforts of the communicators: “Our work was going well, but after our president’s declaration, we could see a setback in the streets. People who were at home started to feel safer and to go outside.”

The same situation was also noticed in Complexo da Maré. “We need to provide counter-information in response to government announcements. It’s an enormous challenge,” added Martins.

In addition to the negative influence of the federal government, Rafael Oliveira, from Favela Vertical in Gardênia Azul, also revealed the militia’s impacts on the work of communicators in Gardênia Azul. “In moments like these, everything has to be discussed. It is very complicated to enter into dialogue with this kind of authoritarian power,” explained Oliveira. By order of the paramilitaries, for example, the shops in which the militia’s wide range of activities take place have been reopened. They also have received reports that the militia has been coercing residents into requesting the government’s emergency aid and then delivering it directly to them.

Despite these additional barriers, mobilizers in Gardênia Azul have not given up: “We work with technical problems that are not ours, with political problems that we have to address, and we try to double our impact.” However, Oliveira is realistic about the roots of the crisis that affects favelas and the support that community organizers and communicators have been giving families: “It is palliative work that heals some wounds, but it does not save the sick.”

Despite these additional barriers, mobilizers in Gardênia Azul have not given up: “We work with technical problems that are not ours, with political problems that we have to address, and we try to double our impact.” However, Oliveira is realistic about the roots of the crisis that affects favelas and the support that community organizers and communicators have been giving families: “It is palliative work that heals some wounds, but it does not save the sick.”

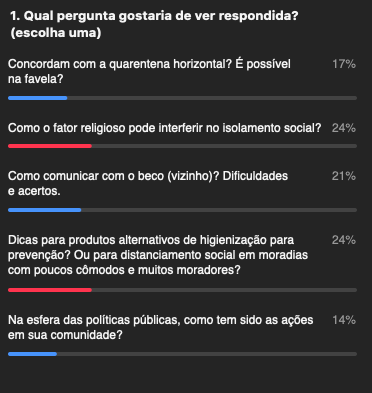

One of the questions that most concerned the virtual audience at the forum was: “How is religion interfering with social isolation?” Unanimously, all speakers agreed that churches have a huge influence on the community. As experiences were shared, it was clear that religion plays a different role across different communities.

In Maré, Martins explained that in the early days, the churches collaborated with the communication work. “They put their own cars on the street, broadcasting evangelical and Catholic songs, and recommending after the songs and prayers that the population stay home,” she said. In São Paulo, Rodrigues explained that “churches [in Paraisópolis] could play a very important role in helping people to stay at home, but instead they have played a different role.” Rodrigues reported that many evangelical churches continue to function normally and “are quite crowded.” Oliveira pointed out that, within the variety of churches that exist in Gardênia Azul, evangelical and protestant churches do not support isolation, but Catholic churches, Spiritist centers, and Afro-Brazilian centers (Umbanda and Candomblé) are collaborating.

Andrade pointed out that, in Vila Kennedy, at first, “evangelical pastors supported the idea of quarantine, closing their churches and streaming online worship,” but she noticed that after the president’s announcements against social isolation measures in favor of the economy, “the small churches started to open, and the other bigger churches are opening, but with restrictions.”

An Exchange to Be Repeated

Other problems specific to favelas, but also related to coping with the consequences of the worldwide coronavirus pandemic, arose from contributions by people watching the teach-in online. Concern around people’s mental health and mental illness, as well as an increase in cases of domestic violence during the period of physical isolation, were topics that were extensively addressed during the “open microphone” portion of the forum. Doubts and concerns were also expressed about the data released by the government—that is, the real number of infections and deaths for both favela residents and the general population.

In this sense, all of the guest speakers are aware that this new struggle is just beginning. The commitment of the community organizers could be summed up by Ilaci Oliveira’s words: “It’s a custom in the favela: if you shout for help, 2,000 other people will come to your home to help you.”

Watch the teach-in in Portuguese here:

*RioOnWatch and the Sustainable Favela Network are initiatives of Catalytic Communities