This is our latest article on the new coronavirus as it impacts Rio de Janeiro’s favelas.

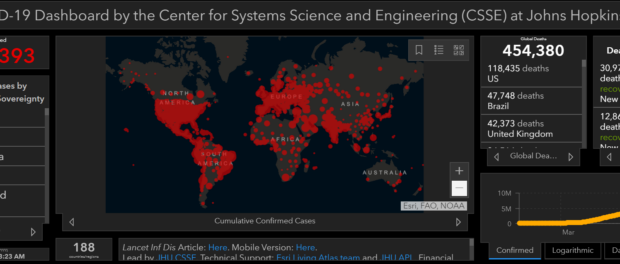

On June 12, Brazil surpassed the United Kingdom, and now holds the world’s second-highest Covid-19 death toll. And yet, amid concerns of widespread underreporting—especially in the favelas and peripheries—Brazil’s true figures may far surpass its official record of over 52,700 deaths and 1.15 million confirmed cases. These concerns have taken on new urgency since the federal government took steps to modify and then restrict the publication of national-level Covid-19 data. The same was also done in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro.

A Brief History of Covid-19 Case and Death Reporting Methodology in Brazil

On June 6, the Ministry of Health tried to fundamentally change Brazil’s case and death reporting methodology. The executive body pulled months of data, removing the total number of confirmed Covid-19 cases and deaths since the pandemic’s onset, leaving only a daily total of new confirmed Covid-19 cases and deaths over the last 24 hours.

Justifying its choice to remove accumulated totals of Covid-19 confirmed cases and deaths, the Ministry of Health said that “[t]he new publishing model for information about Covid-19 will address the current panorama of the disease” because “[i]n the publication, purely, of accumulated cases… it is very difficult to verify changes to regional, state and municipal scenarios.” The removal flew in the face of World Health Organization (WHO) surveillance strategies guidance, obscuring comprehension of the overall progression and evolution of the pandemic.

The Ministry also switched from compiling data of Covid-19 deaths according to the date on which the death was recorded, as is common in the majority of countries, to compiling data of Covid-19 deaths according to the date on which the death occurred. The Ministry reasoned that the switch was necessary because the internationally-accepted system led to the publication of “cases of laboratory results of deaths recorded weeks ago, but that count for the accounts of that day.”

The effect was a net reduction in reported Covid-19 deaths. According to estimates by newspaper Folha de São Paulo, the switch left at least 44% of coronavirus deaths out of official data publications, as Covid-19 confirmation often only becomes available post-mortem. The same analysis also points to political interference, noting that “[t]he government started to talk about changing the publication methodology after Brazil broke consecutive [daily] records for deaths.”

On June 8, Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes ordered the Ministry to return to its previous data publication methods, saying that the “constitutional consecration of publicity and transparency equates to the obligation of the State to provide necessary information to society.”

Although the crisis was short-lived, public response and international backlash underlined the critical importance of the publication of accurate data in Brazil. Changes in reporting methodology shape the information available to health professionals, policy-makers and the general population, altering everyone’s ability to make informed decisions.

The Impacts of Case Definitions on Covid-19 Reporting Methodology

Reporting Covid-19 data starts with case counting. The WHO uses a three-tier system for counting and reporting Covid-19 cases: suspected, probable, and confirmed, with the last tier defined as a “person with laboratory confirmation of Covid-19 infection, irrespective of clinical signs and symptoms.” This is the only tier of the case reporting system that relies on laboratory test results to confirm the presence of the virus and is only one part of the data equation when it comes to providing data for effective policy-making.

For the WHO’s five other definitions (three for suspected cases and two for probable cases), clinical observations of symptoms are required to confirm or deny the possibility or probability of the virus. In the context of the global shortages in testing capacity, the results of clinical observations become critical.

Brazil uses a two-tier system, counting only suspected and confirmed cases. “Confirmed” cases, as the WHO recommends, require laboratory test confirmation. Health professionals and institutions from both public and private sector health units are required to report all suspected and confirmed cases to health authorities. However, in Brazil only confirmed cases are being published on official data dashboards.

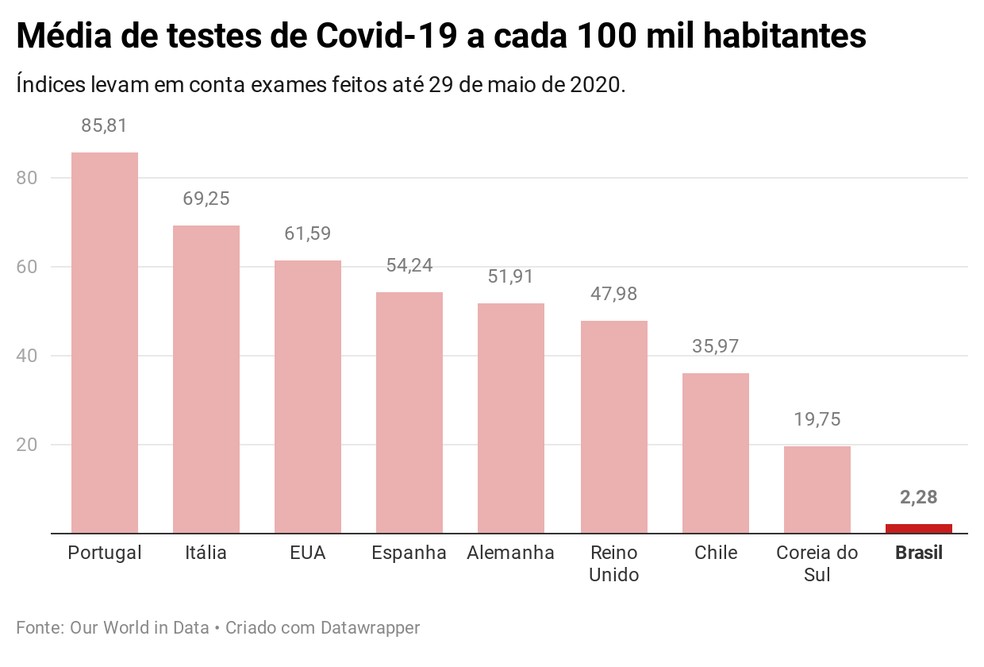

As only confirmed cases are published on official data dashboards, and cases can only be reported as confirmed by laboratory testing, then Brazil’s testing capacity is crucial. However, Brazil has been severely under-testing since the beginning of the pandemic. The WHO recommends that countries conduct sufficient testing such that an average 5% of tests return positive daily—Brazil averages a 36.7% positive rate. That is: only the most dramatic and visible of cases are being tested.

The report also points out that not all laboratories conducting tests are registered in the system from which the Ministry of Health receives test results, meaning that the Ministry is not accessing all available Covid-19 data.

Political Influence in Covid-19 Reporting Methodology

In a recording of an April 22 cabinet meeting, President Jair Bolsonaro told ministers and members of the government to emphasize patient comorbidities when recording Covid-19 deaths so as to decrease the official numbers being published as Covid-19.

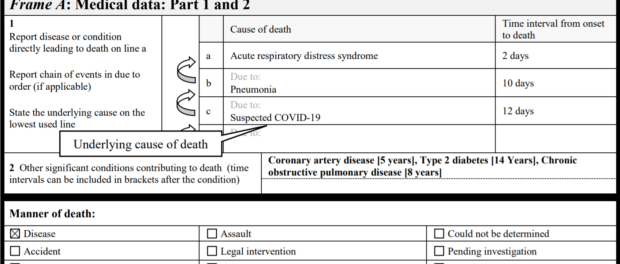

The primary objective of the WHO International Guidelines for Certification and Classification (Coding) of Covid-19 as Cause of Death, is to “identify all deaths due to Covid-19” to facilitate an inclusive system for the practice of registering deaths for official publication:

A death due to Covid-19 is defined for surveillance purposes as a death resulting from a clinically compatible illness, in a probable or confirmed Covid-19 case, unless there is a clear alternative cause of death that cannot be related to Covid disease (e.g. trauma). There should be no period of complete recovery from Covid-19 between illness and death.

The WHO’s reporting system does not allow Covid-19 deaths to be attributed to comorbidities. Rather, it specifies a way of mapping the chain of clinical events to determine the causal sequence leading to death while clearly underlining the underlying cause of death. The system allows the medical history of the patient to be documented as accurately as possible throughout the course of the illness(es). If a patient has comorbidities, the system registers them in a separate section of the form. In these cases, death is always classified as “due to COVID-19.”

In a near-direct translation of the document, Brazil’s Ministry of Health included in its WHO-mimicked guidance a modification to the instructions. The change is relevant to the president’s request that “whoever has the right, the respective ministry” include less deaths due to Covid-19 in official reports. The guidelines state: “If, at the time of filling in the Death Certificate, the cause of death isn’t confirmed as due to Covid-19, but there is a suspicion [it was], the doctor will write down “suspected Covid-19” in part 1 [for cause(s) of death].”

The Brazilian guidelines then explain that the “recommendation for filling-in “suspected Covid-19” is international and aimed at capturing all possible deaths from the illness” but that ultimately, in Brazil:

The confirmation or ruling out of Covid-19 will remain the responsibility of the Municipal and/or State Health Secretariats.

The information that remains after this initial sorting process is then passed on to the Ministry of Health, who themselves “consolidate” the data before publishing it each day. The Ministry of Health does not publish suspected Covid-19 deaths on its official data dashboards, but the sequencing of this kind of data mining demonstrates the range of options available to public authorities in shaping published figures to discount the full impact of the pandemic.

Best Practices from Belgium

In what might be seen as a 180° approach from Brazil, in Belgium, the public health institution Sciensano, in charge of the country’s Covid-19 response, uses a simplified version of the WHO Case definitions for surveillance to allow for the highest rate of reporting to provide the maximum amount of data. Moreover, in Belgium, it is obligatory for health professionals and institutions to declare “all possible cases.” Sciensano then identifies “the number of cases, whether or not confirmed” and “the number of deaths, suspected or confirmed” for their data collection and analysis. Belgium’s approach has been touted as that providing the most accurate accounting of the virus.

Sciensano publishes suspected Covid-19 cases inside and outside hospitals in their official figures. This is because they consider suspected cases as important as confirmed cases. In the absence of full testing, counting suspected cases is the best proxy to approach accuracy. Belgium has sought to avoid underestimating Covid-19 cases and deaths as a primary goal. Sciensano considers it “good standard practice” to record confirmed and suspected cases, following the recommendations of the WHO and the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control.

The result of Belgium’s inclusive counting and reporting methodology is that the country has very high Covid-19 case and death rates for the size of the population. The Prime Minister Sophie Wilmès explains that “Belgium has chosen the greatest transparency in communicating deaths linked to Covid-19.”

In contrast, President Jair Bolsonaro has consistently implied that Brazilian Covid-19 data are inflated. Rather than meet the pandemic with Belgian-style transparency, the government here has opted to flout WHO guidance on Covid-19 surveillance strategies. Amid cries against underreporting, insufficient testing, and their devastating consequences, the federal government continues to manipulate publicly available data in an effort to skew perceptions over its handling of the pandemic.

Government-released data dictates the official representation of the reality experienced by Brazilians to domestic and international observers. In opting to abscond and distort official Covid-19 figures, the Ministry of Health has scrapped public safety, leaving Brazilians at the mercy of a still growing, and increasingly ravaging pandemic.