This is our latest article on the new coronavirus as it impacts Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, and the first ever obituary published on RioOnWatch.

With his college entrance exam preparatory courses suspended due to the Covid-19 pandemic in mid-March, Nilton Gomes Pereira, lovingly known as Diquinho, turned his rooftop into a storage space for donations. The concrete rooftop terrace, or laje, that Diquinho had used to teach everything from Portuguese grammar to sociology to proletariat revolution would instead house food parcels and hygiene kits destined for the families of Complexo do Alemão.

His home, one of a cluster of apartments carved into the Morro da Baiana hill, one of the favelas within the Alemão favela complex, now stands vacant. The 71-year-old passed away on April 14, tragically, most likely to coronavirus, and a gutted public health system.

Asking around the community today, Diquinho is best known for his prep course, his ubiquitous presence at community events, and his fierce defense of working people. A self-described Trotskyist-Leninist, the 50+ year favela resident would rail against oppression by the bourgeoisie, decrying the charade of Brazilian party politics to his dying day.

Far from anachronistic, friends cautioned, he was, in the true sense of the phrase, a member of the old guard: a now-shrinking group of favela revolutionaries who laid the groundwork for today’s modern favela collectives and human rights groups, guaranteeing the very existence of favelas throughout Brazil.

Early Life

Life in the eastern interior of Minas Gerais state exposed Diquinho to questions of class struggle early on. Son to a landless farmer, Diquinho would later recount that the family was forced to move to the nearby city of Caratinga after he turned seven. A landowner had seized a coffee plot cultivated by Diquinho’s father; his father sued for damages, but lost in court.

Though his father soon found work as a stonemason’s assistant in Caratinga, earning enough to cover the children’s primary school, Diquinho’s high school education was cut short when a government scholarship he received lost funding. Even then, Diquinho had already begun to work, laboring at a textile factory before learning typography at age 13. The profession would provide him with sporadic income for the rest of his life.

By the time Diquinho moved with his mother and siblings to Rio de Janeiro in 1967, Brazil’s military dictatorship had already abolished political parties and ratified a new, oppressive constitution. Having ousted President João Goulart in a supposedly temporary coup three years prior, the dictatorship had since made it clear it wasn’t going anywhere. For opposition movements, including the armed 8th October Revolutionary Movement (MR-8), this would mark the beginning of concerted underground resistance. For 18-year-old Diquinho, it was the beginning of a political awakening.

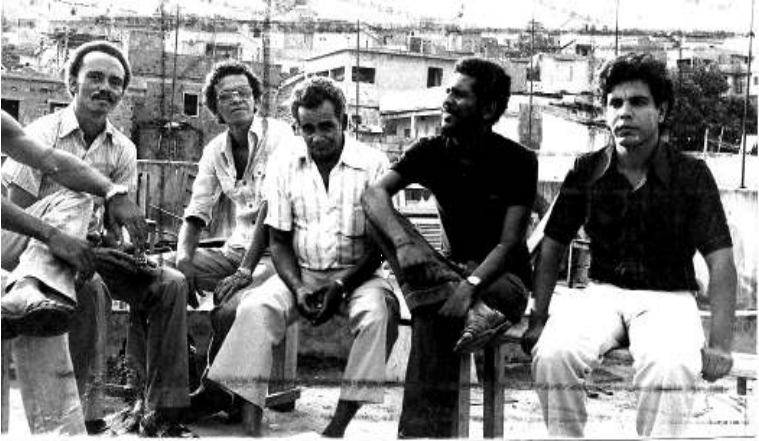

Having settled in the growing neighborhood of Complexo do Alemão with his mother and siblings, Diquinho kept up his typography work and began to attend union meetings, later connecting with members of MR-8. Then in his mid-twenties, Diquinho met with four MR-8 activists studying at the nearby Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). Together, the five worked to found a high school entrance preparatory school for adults. Diquinho, having never completed high school himself, participated in the classes taught by the university students for the next year and a half, diving into the question of political training. He would formally join MR-8 in 1974, participating in the Joaquim de Queiroz (Grota) Residents’ Association the following year. There, at the Grota Residents’ Association, Diquinho squared off with utility companies and the government, fighting for improved sanitation infrastructure and equal energy pricing for the favela. Diquinho’s organizing in Complexo do Alemão soon caught the attention of the Federation of Favelas of the State of Rio de Janeiro (FAFERJ).

Taking Back the FAFERJ

Founded in 1963, FAFERJ (initially the Federation of Favelas of the State of Guanabara, FAFEG) had become an immediate target for the dictatorship. With the imposition of the military government’s Institutional Act 5 in 1968, a measure that gave sweeping powers to the executive, effectively dissolving constitutional guarantees, the State had scaled up its persecution, conducting mass arrests of opposition figures. As torture, forced disappearances and murders became commonplace, FAFERJ lost its legs, falling under the tight control of dictatorship-aligned Governor Antonio Chagas Freitas. The governor’s charitable body, Fundação Leão XIII, had taken the reins of the federation’s internal leadership, using a clientelistic relationship with favela residents’ associations to push for removals rather than favela upgrades.

By the time Diquinho ran for a spot on the FAFERJ directorate in 1979, the Federation had failed to save upwards of 100,000 favela residents from a wave of evictions in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Attempts to remove the highly visible South Zone favela of Vidigal—later blocked by a team of organizers, lawyers, and a crucial visit by Pope John Paul II—were ongoing. Comfortable in his role as Chagas-chosen FAFERJ president, the incumbent Francisco Souza took no efforts to hold mandated elections at the end of his term in 1978. Sensing an opportunity, Diquinho and others moved into position.

A group including the Catholic Church’s newly-formed Favelas Pastoral Committee, MR-8, and the Brazilian Communist Party (PCB) demanded elections for a new directorate to take office in 1979, recruiting community organizer Irineu Guimarães from the North Zone favela of Jacarezinho for president and Diquinho as vice. When the team won handily, a stubborn Souza and Fundação Leão XIII refused to recognize the results, contending their choice, Jonas Rodrigues, would assume the presidency. For the following year and a half, the “two FAFERJs” would square off in the press and in-person, as the state-backed “FAFERJ 1” and opposition-elected “FAFERJ 2” fought for the title of the rightful representative of Rio favelas.

As the public split raged on, the Guimarães-Diquinho team and the Pastoral das Favelas took advantage of FAFERJ 1’s increasingly non-representative and anti-democratic image. Working to found and consolidate favela residents’ associations across the city, focusing on the West Zone favelas and the North Zone area of Leopoldina, Diquinho pushed not only for institutional consolidation, formalizing associations’ basic documentation, but for political awareness-building (conscientização) and democratic engagement.

Emblematic of Diquinho’s work was the case of Morro da Baiana, which, though occupied in 1961, became subject to removal via eminent domain in 1980. In response, in addition to the arduous task of gathering community documentation to prove ownership, Diquinho aided a literal occupation. Summoned on account of his position on the FAFERJ directorate, Diquinho assembled a team of FAFERJ members, a local priest from Olaria’s São Geraldo Church, and Civil Police Delegate Hélio Luz (Luz, later Chief of Rio’s Civil Police, reportedly shooed away a group of Military Police that had arrived without a warrant), camping out overnight along the hillside. He would later help found Morro da Baiana’s residents’ association.

FAFERJ unification, however, would not take place until 1982 with a Chagas-mediated compromise that recognized Guimarães as official FAFERJ president on the condition of maintaining entrenched Fundação Leão XIII control internally. MR-8, seeking to build interclass alliances as Brazil inched its way toward re-democratization, supported the compromise. For Diquinho, still firmly committed to the implementation of socialism, this was too much. He would officially separate from MR-8 shortly after, breaking with the PMDB opposition party and stepping off of the FAFERJ directorate.

He would return three years later when FAFERJ presidential candidate Nahildo Ferreira won the Federation’s 1985 elections with a directorate that included Diquinho as well as burgeoning community organizers Itamar Silva and Eliana Sousa Silva. The group managed to reform the FAFERJ’s statutes, making directorate elections, for the first time, subject to a direct vote by favela residents affiliated with residents’ associations. Diquinho would later form his own FAFERJ ticket in 1988, losing to Guimarães in the federation’s first democratic election.

In the backdrop, in 1982, Leonel Brizola of the Democratic Labor Party (PDT) had become Rio de Janeiro’s first democratically elected governor since 1965. Diquinho, who had made a failed run at Rio state deputy with the PDT in 1986, would later join the Brizola government in its second mandate from 1991 to 1994. Working in the state’s Commission on Land Issues (Comissão de Assuntos Fundiários), Diquinho would again aid favela communities in consolidating ownership documents and protecting themselves from eviction. No favela removals would take place under the government of Brizola or successor Marcello Alencar.

Diquinho entered politics one last time with the election of Hélio Luz as state deputy under the Worker’s Party (PT) in 1998, working in Luz’s cabinet through 2003, and later affiliating himself with the PSOL (Socialism and Liberty Party). The next several years would bring stark disillusionment with both political parties and the favela residents’ associations he had worked so hard to found. Leftist parties, for Diquinho, including the PSOL, had abandoned the revolutionary cause; residents’ associations had either fallen prey to political ends or into the hands of drug traffickers.

For Diquinho, the only remaining hope lay at the grassroots level: in the fight for favela resident demands, the formation of organizing committees, and political training. Thus, when the government of President Luiz Inácio ‘Lula’ da Silva announced R$600 million in public works for Complexo do Alemão under the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC), set to begin in 2008, Diquinho set to work.

Eschewing dialogue with local residents associations, Diquinho worked through a number of existing and newly created committees to develop a pro-positive agenda of resident demands to be included in the PAC works and present them directly to PAC administrators. This included the Popular Council of Complexo do Alemão, a group Diquinho co-founded in 2009; the Committee for the Local Development of the Serra Misericórdia (CDLSM-RJ), a group first created in 2000; and newly formed committees on health and education.

The group’s PAC demands included an overwhelming demand for water connectivity, formal sanitation, and paved roads. Final PAC constructions, despite completing some of the educational and leisure spaces Diquinho had hoped for, also included a wildly expensive and soon-to-be inoperative cable car system. Sanitation, water, and pavement improvements were left undone in wide swathes of Complexo do Alemão.

The event deepened Diquinho’s disappointment in traditional government engagement as well as his conviction in the thought that true change would only come through revolution. Rather than give up hope, Diquinho focused his efforts on educating and training the new generation of Alemão leaders. After co-founding Complexo do Alemão’s Popular Council—based on a similar Rio-wide model at the Pastoral das Favelas—he launched the Council’s college entrance exam course less than a year later. Over the next ten years, he would teach, speak, organize, and protest alongside a new generation of favela leaders.

Training a New Generation

Former students credit Diquinho with their first feelings of political awakening and class consciousness. Diquinho turned his students on to black intellectuals such as Abdias Nascimento and Lélia Gonzalez and regaled them with stories of MR-8’s resistance against the military dictatorship. Members of the Occupy Alemão and Escola Quilombista Dandara de Palmares social projects name Diquinho as key to their founding. Longtime Complexo do Alemão historical organization Raizes em Movimento has committed to keeping his memory alive, emphasizing that Diquinho’s story is one with impacts not just for Alemão or even Rio, but on a national level.

In interviews with RioOnWatch, friends, colleagues, and allies called him “a selfless revolutionary,” “a relic for future generations,” “a true autodidact,” “dedicated,” “relentless in the fight for socialism,” “crucial to the construction of the favela movement in Rio,” a man of “national projections,” and “a great companion.” In his final days, he had railed against the government as well as the wave of attacks on a struggling public health system; in his treatment at public health posts in Alemão and Manguinhos, he received no test for Covid-19.

He would die in his home in Morro da Baiana, in a favela he molded with his own hands, surrounded by the favela youth he had trained and educated. Diquinho had no children. “A true activist,” he said in a 2013 interview, “is the owner of himself. He belongs to the cause.”

References and Additional Reading:

- Hard Times in the Marvelous City, by Bryan McCann

- Interview with IPEA’s Patricia Couto, 2013

- Interview with Eladir Nascimento, 2007

- “E por falar em FAFERJ… Federação das Associações de Favelas do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (1963 – 1993) – memória e história oral,” by Eladir Fátima Nascimento dos Santos

- Wikifavelas: Associações de Moradores do Alemão

- Wikifavelas: Diquinho: Liderança (entrevista, 2013)