Mass protests in the United States have sparked a debate about how to end police violence globally, even as cases elsewhere are characterized by different historical realities. These differences must be considered in order to trace next steps forward, say Brazilian activists.

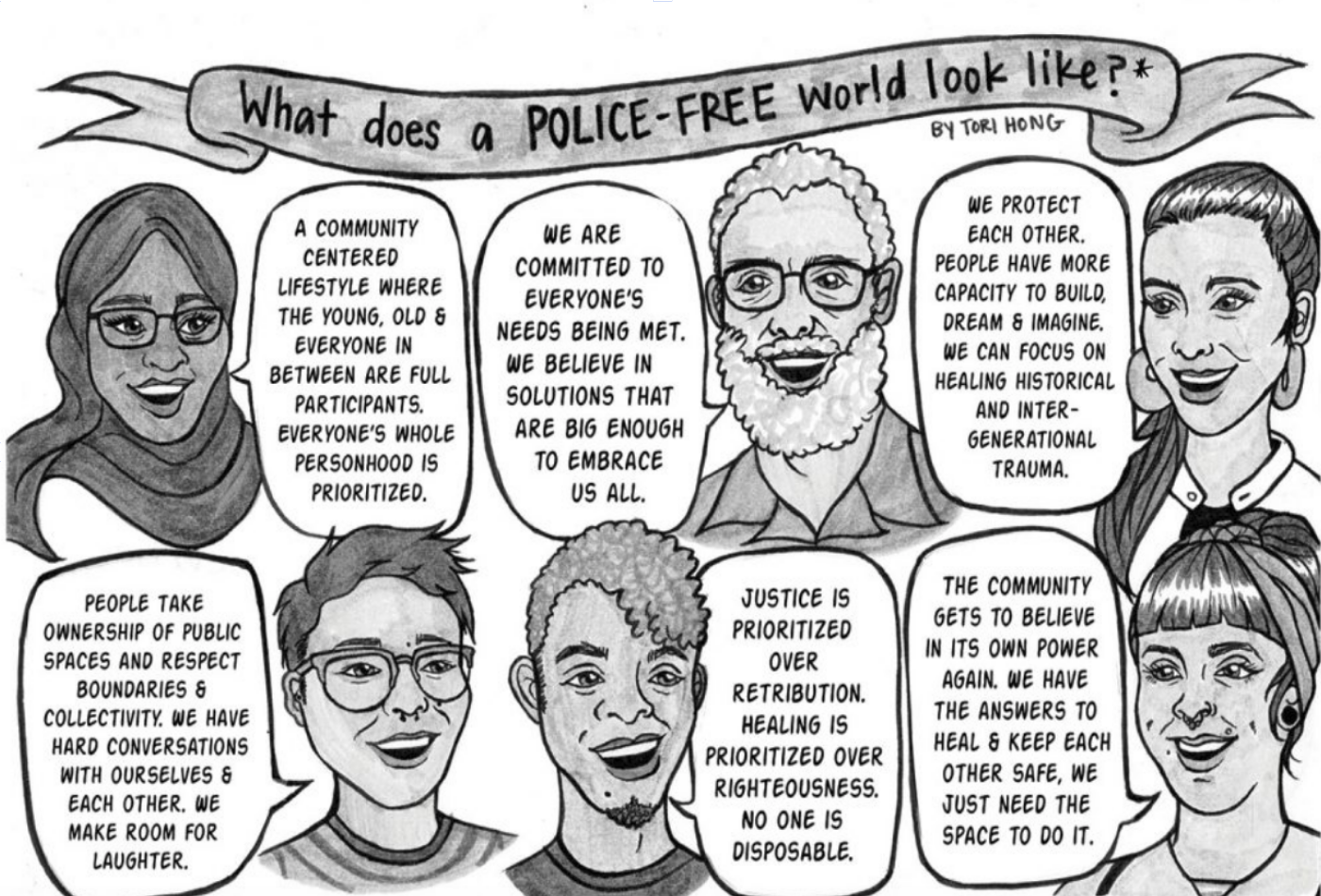

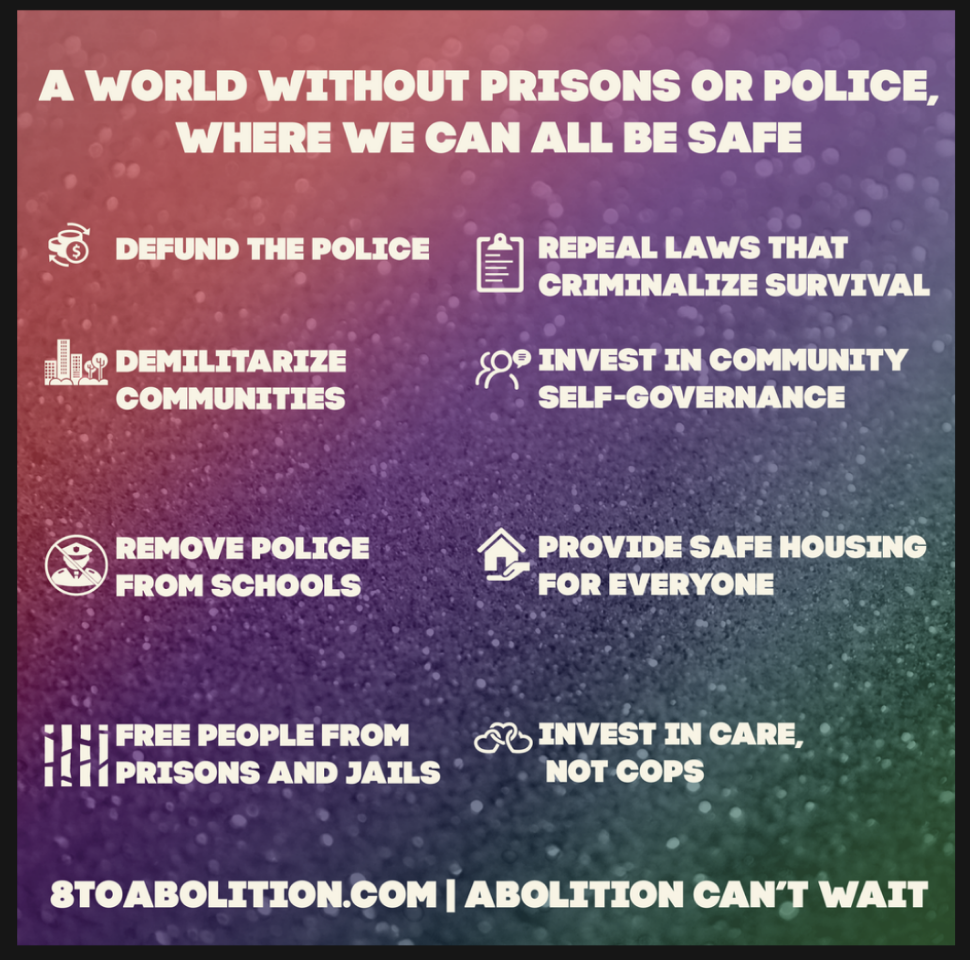

Over the past 200 years, societies across the Americas have been shaped around the idea that police and prisons are equivalent to safety and security. Though movements for the abolition of police and prisons are not new, demands to divest from these forms of punishment have taken on an unprecedented scale in recent weeks. Movements like 8 Can’t Wait in the U.S. known for its focus on proposing steps toward police reform, have now moved further. Abolitionists are urging such movements and the broader public to imagine a world without police or prisons: one in which systems of care and accountability replace punishment and violence. But what would this world look like?

In the U.S., the grassroots abolitionist organization Critical Resistance defines abolition as a political vision that aims to eliminate imprisonment, policing, and surveillance while creating lasting alternatives to punishment and incarceration. As prison abolitionist and scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore points out, “abolition is about presence, not absence. It is about building life-affirming institutions.” Scholar and Critical Resistance co-founder Angela Davis said in a June interview that “abolition is really about rethinking the kind of future we want…it’s about revolution.” For MPD150, a participatory initiative based out of Minneapolis, police abolition means a gradual process of reallocating funding, resources, and responsibility away from police and toward community models of support, safety, and prevention.

In Brazil, some activists have for years called for an end to the Military Police. Many of them identify themselves as anti-punitive—opposed to the logic of punitive consequences—and increasingly, several identify themselves as prison abolitionists. “When we defend a world without prisons, we are going to talk about alternatives for resolving conflicts,” said Juliana Borges, the author of What is Mass Incarceration?, in a 2018 interview.

The idea of abolishing police and prisons is fundamentally about re-envisioning society. Taking on different forms depending on local contexts, proposals for abolition offer a transnational lens to transformative change. They question current systems of justice and propose alternatives for guaranteeing security and accountability by asking: Does police presence make communities safer? Do prisons make societies safer?

Abolitionists not only answer no, but also argue that prisons and police are fundamentally violent. However, shutting down prisons and scrapping police forces is not their ultimate goal. It is rather a means. With the goal being community safety, and given their recognition that safety is not achieved by the existing model, they then focus on the alternatives. What is the answer?

Simply put: policing and incarceration must be replaced by networks of care and support. As Angela Davis writes in her book, Are Prisons Obsolete?, “we would try to envision a continuum of alternatives to imprisonment: demilitarization of schools, revitalization of education at all levels, a health system that provides free physical and mental care to all, and a justice system based on reparation and reconciliation rather than retribution and vengeance.”

The proposals and demands being vocalized in the United States can serve as inspiration for militarized societies worldwide. So, too, can autonomous organizations that function without police intervention, such as Mexico’s Zapatista caracoles and Brazil’s Quilombola communities. Brazilian photojournalist Rafael Daguerre brought up these two examples in a recent online discussion titled “Is the End of the Police Possible?.” The event was organized by the Right to Memory and Racial Justice Initiative, a forum for discussing public security and race based in Rio de Janeiro’s northern outskirts, the Baixada Fluminense.

During the discussion, Priscilla Ferreira, a Brazilian activist and post-doctoral researcher in Black and LatinX studies at the University of Texas at Austin, spoke about her experience working with young criminal offenders in an environmental re-education project in North Carolina. The project transformed six former prison buildings into a sustainable farm. “I did a Theater of the Oppressed (participatory theater technique pioneered in Rio in the 1960s) project with them there, and I can say that the sensation they had of agency and cleaning of trauma was real.” Ferreira said that this example, along with several Brazilian initiatives, “is an opening for us to investigate and reimagine.”

Abolitionists believe that plans of action must be tailored to local contexts and changing sociopolitical landscapes rather than a one-size-fits-all solution. “It doesn’t work to bring an abolitionist proposal to Brazil, sourced in European thought, that doesn’t recognize our differences,” Monique Cruz, a member of the Manguinhos Social Forum and researcher at NGO Justiça Global, said in an interview.

Why Abolition?

Brazilian abolitionists believe that envisioning a society without police and prisons is urgent due to the country’s deep-rooted racism, state-sponsored violence, and structural inequality. In a 2019 interview with news site Nexo, Brazil’s former National Secretary of Public Security, Luiz Eduardo Soares, discussed this context in detail, saying that mass incarceration is not only ineffective but also reinforces cycles of poverty, strengthens criminal networks, and systematically singles out young, black men. According to Soares, 28% of people in Brazilian prisons were detained on drug charges, despite the fact that many of them were not involved in organized crime or violence at the time of detention. He listed many obstacles to changing the status quo: that the Left has failed to propose concrete alternatives to public insecurity, even as they criticize it, that prisons serve to multiply organized crime, and that sustainable progress cannot be made until drugs are decriminalized.

While historically more Brazilian activists have focused on the demilitarization of police and reduction of prison populations (decarceration) rather than on abolition, many call for a long-term goal of abolition as well. There are multiple strains of thought within the Brazilian prison abolition movement. In a presentation last November to the São Paulo State Front of Decarceration, historian and writer Suzane Jardim said that due to the history of prisons in Brazil and the profile of prisoners today, for her, “essentially, prison abolition is a black struggle.”

Brazil’s prison population, which surpassed 755,000 inmates in December 2019, is the third largest in the world, behind China and the U.S. 30.4% of those incarcerated in Brazil are in pre-trial detention, according to 2019 data from the National Penitentiary Department.

In a 2013 public hearing with the federal government, civil society groups and social movements proposed a decarceration program. The resulting National Agenda for Decarceration contains five main demands: a halt to investment in new prison units, sentence reductions and decriminalization of drug-related conduct violations, expanded civil society access to prisons, the end of private prisons, the demilitarization of police, and end of torture. Rather than incorporating any elements of this agenda, to date, state and federal public security policies have overwhelmingly dismissed it. As the Wilson Center reported, as of August 2019, Brazil’s incarceration rate was continuing to rise, and its prison population is projected to reach 1.5 million by 2025.

Similarly, calls for demilitarization have been ignored by politicians. Rio’s governor, Wilson Witzel, has often used militaristic rhetoric, whereby Rio’s favela communities are battlegrounds where police “slaughter” those who break the law. He has frequently referred to drug offenders as “narco-terrorists.” In a similar vein, President Jair Bolsonaro called protesters against his government “terrorists” and threatened to deploy federal troops on a weekend in which nationwide demonstrations included messages against racism and state violence.

As Luiz Eduardo Soares explained in his book, Desmilitarizar, proponents of demilitarization typically vouch for reform of the Military Police (the Military Police is responsible for maintaining public order; the Civil Police investigates crimes). Soares writes that this call fails to acknowledge that the entire face of public security in Rio is militarized, and therefore must be reinvented. Rio’s police system has maintained itself since colonial times, for 200 years, with little reform, and continues to replicate tactics used during the military dictatorship (1964-1985). He argues that demilitarization alone cannot correct for impunity, institutional violence, extrajudicial killings, and many other human rights violations.

When Reform Isn’t Enough

The thousands of #BlackLivesMatter protesters who have taken to U.S. streets in recent months express a view that efforts at police reform in the country have so far failed abysmally. Initiatives ranging from chokehold bans to body cameras have proven ineffective and in some cases have been counterproductive. After Michael Brown was fatally shot in Ferguson, Missouri by police officer Darren Wilson in 2014, reformists called for police departments to require their officers to wear body cameras, with the intention of creating more oversight and accountability. Nonetheless, a 2019 study conducted at George Mason University on officer-worn body cameras found scant evidence that the technology has reduced police misconduct; instead, the researchers report that “officers primarily use [cameras] to increase the accountability of citizens.” Many police units also prevent citizens from viewing footage, undermining the aim of transparency.

Understanding failed police reform in Brazil begs a look at the UPP—Rio de Janeiro’s Pacifying Police Units. Created in 2008, the program aimed to de-escalate a paradigm of violent, militarized police incursions in favelas and remains the largest-ever and most recent attempt at community policing in Rio de Janeiro. While the scant previous police reform efforts in the city had proven disappointing, the first couple of years of the UPP program appeared promising: homicide rates fell and the favelas and “the asphalt” (formal city) became more interconnected.

That said, it wasn’t long before this cautious trust began to disintegrate: cases of police brutality and enforced disappearances exposed the shaky foundation that the entire police system rested on and the lack of fundamental changes. In July 2013, Amarildo de Souza, a bricklayer from Rocinha, was interrogated by the UPP and never seen again. Amarildo’s case was the final straw and sparked nationwide outrage, revealing deep inconsistencies between the UPP’s supposed role in favelas and its actions.

More recently, during the coronavirus pandemic, Rio’s government has not only neglected to provide basic services to favela residents but has also continued militarized police operations. On June 5, after widespread #BlackLivesMatter protests, Supreme Court Justice Edson Fachin ordered Rio’s police to halt their raids in favelas for the duration of the pandemic. The ban on police operations was vague and contained the caveat that it would not apply in “absolutely exceptional cases.” Just two weeks later, Fogo Cruzado, a digital platform that tracks shootings in Rio and Recife, recorded a police operation in Morro da Providência. That night, an armored police car was spotted in the favela, and dozens of community members shared audio recordings and videos of the gunfire on Twitter. Two days later, similar footage from the North Zone area of Cidade Alta flooded Twitter. Such instances reveal the inherent limits of police reform in a context in which repressive, deadly tactics are deeply ingrained.

Reform maintains the current system as it stands, which abolitionists contend reinforces a culture of brutality, not security. Common reformist proposals include extensive police training programs and oversight committees, yet these hoped-for improvements can backfire by funneling more money and resources to police without guarantees of change. What may be seen as an alternative, effective, yet still reformist (since it does not do away entirely with the criminal justice system, but instead dramatically reduces it), is the Washington, DC-based Time Dollar Youth Court which ran from 1996-2009 with exceptional success, putting first-time non-violent offenders up before a jury of their peers (former first-time offenders who have gone through the program). Tellingly, TDYC closed due to short-sighted drops in funding, despite it being cheaper than locking youth up and keeping large numbers of youth from prison. Consequently, abolitionists say that envisioning an end to the police and prisons may offer the only promising path to achieve true change—which, in Brazil, would entail a complete reconstitution of the justice system so that it no longer leverages divisive militaristic tactics at citizens.

The Road to Abolition

Abolitionists believe that calls for police reform often fail to acknowledge the connection between police and socioeconomic structures such as white supremacy, capitalism, and heteronormative patriarchy. To Ferreira, “white supremacy is a huge affective and spiritual loss. It is a form of domination that disintegrates one’s being.” Ferreira said that for her, the road to abolition relies on Afro-feminist Quilombismo—a road that is, at its core, antiracist and anticapitalist. But what does this look like in practice?

Abolition calls for community accountability and transformative justice as alternatives to policing and incarceration. Community accountability addresses violence directly while also nurturing a culture of mutual and collective responsibility. Meanwhile, transformative justice seeks to provide immediate safety to victims of violence and to offer long-term healing and reparations by holding those who commit harm accountable. These approaches not only address current incidents of violence but also prevent it from recurring. The U.S.-based writer, educator, and community organizer for disability justice Mia Mingus explains that violence does not happen in a vacuum, and transformative justice “recognizes that we must transform the conditions which help to create acts of violence or make them possible.” That is, the status quo fails to offer long-term solutions and ignores the compounding effects of racism, sexism, and homophobia on violence.

Many Brazilian organizers argue that in order to imagine alternative futures without police and prisons, the country’s complex history of white supremacy, miscegenation, and the myth of racial democracy must be acknowledged. “If we don’t get people to… [understand] the fact that racism is structural and fundamental to the prison issue, then we will also have difficulty [creating] perspective for an abolition movement,” said Cruz. She believes that re-education is essential to spark a cultural shift in Brazilian society—one which will lead to more widespread acceptance of the changes that abolition calls for.

“We have social practices that reproduce differences in relation to who is and isn’t considered a citizen,” Cruz said. She criticized the popular saying “a good criminal is a dead criminal,” which she said “was totally constructed on racial notions of who the potential criminal is” and demonstrates how structural racism and the criminalization of poverty are deeply ingrained in the Brazilian psyche.

For abolitionists worldwide, a dilemma arises when victims of state violence call for the imprisonment of a police officer who killed someone. They acknowledge that as long as the only justice system people know is that of incarceration, calling for the penal system to correct a wrong can help a victim’s relatives and loved ones mourn, as it publicly recognizes their pain. Furthermore, such families are often from marginalized groups with limited access to the justice system, so the ability to leverage such consequences on the perpetrator is powerful.

Because of this complexity, many abolitionists advocate for gradual steps and a cultural shift towards new forms of justice. Though current U.S. mobilization has helped bring abolition into a more mainstream light, those who wish to achieve it face a long road ahead.

For readers who are just now hearing about abolition or want to dig deeper into alternatives to penal systems, below is a non-exhaustive reading list written by thought leaders and activists worldwide who discuss how collective hopes for a better future can become tangible realities.

Abolition Reading List

- Angela Davis

- Are Prisons Obsolete?

- Estarão as Prisões Obsoletas? (Portuguese)

- Mariame Kaba

- NYT. “Is Prison Necessary? Ruth Wilson Gilmore Might Change Your Mind”

- Critical Resistance. “The Abolitionist Toolkit”

- The Marshall Project, a nonprofit journal on criminal justice

- TransformHarm.org

- Monique Cruz & Elinton Fábio Romão. “Polícia e Racismo” (Portuguese)

- Interview with Juliana Borges, author of O Que É Encarceramento em Massa? (Portuguese)

- Felipe Barbosa. “Pelo fim do sistema criminal: entenda o que defendem os abolicionistas penais” (Portuguese)

- Coalizão Negra Por Direitos. “Enquanto Houver Racismo Não Haverá Democracia” (Portuguese)

- Acácio Augusto. “Abolicionismo Penal como Ação Direta” (Portuguese)

- A summary of Orlando Zaccone’s Acionistas do Nada (Portuguese)

- The Intercept. “Scholar Robin D.G. Kelley on day’s abolitionist movement can fundamentally change the country [U.S.]”