This is our most recent article on the new coronavirus and its impact on the favelas.

On June 7, Rio-Águas, Rio de Janeiro’s municipal agency for water management, issued a notification to residents of the Santa Luzia favela in the Vargem Pequena area of the city’s West Zone that they must leave their homes within 30 days. As many as 3800 families are affected by this threat, which would leave them all homeless.

According to the Popular Council of Rio de Janeiro, a coalition of communities fighting for housing rights in Rio’s favelas, residents were told that “if they don’t accept to leave, they will lose everything.”

The City justified its threats by arguing that the favela sits in an area with a high risk for flooding, connected with the lack of sufficient public infrastructure.

The Popular Council counters that, “instead of carrying out evictions, the government should formalize and integrate the communities to facilitate residents safely remaining in their homes.” The residents of Santa Luzia have been requesting basic sanitation services and formalization since the 1990s.

Santa Luzia resident Fladimir Fonseca pointed out that, while it is true that the area floods, the flooding impacts the entire area, including the wealthy condominiums of Vargem Pequena, and does not threaten the livelihoods of the residents. “The canals fill up, but after two days, it goes back down. We don’t lose homes or any [belongings],” he explained.

Fonseca thus asserted, “They can’t use this as a parameter to remove us.”

Santa Luzia has a long history with this land going back to 1888, when slavery was abolished in Brazil, according to the Popular Council. Upon emancipation, formerly enslaved peoples received these plots of land, where they lived and grew crops. Much of this land has been passed down through generations, and quite a few current residents of Santa Luzia have resided in the community for over 50 years.

The push to evict the residents of Santa Luzia fits within the historical lack of regard for land and housing rights of favelas, which in their case has manifested itself in a decades-long fight. Fonseca traced the government’s interest in the area back to the mayorship of César Maia from 2001 until 2009, when construction in the area greatly increased and nearby neighborhoods Vargem Pequena and Recreio dos Bandeirantes experienced a population boom.

Construction of condominiums and real estate speculation have continued, and for Fonseca, it is clear that real estate interests are behind the threats of eviction: “We aren’t in a risk area. Rather, we’re in a rich area.” He says that, for the rich, Santa Luzia serves as “visual pollution” that needs to be eliminated.

In September 2006, with the pretext of environmental concerns, the police, along with state-level environmental groups, took part in an operation in Santa Luzia with the goal of deterring the growth of the community, which is close to the Parque Estadual da Pedra Branca, one of the world’s largest urban nature reserves.

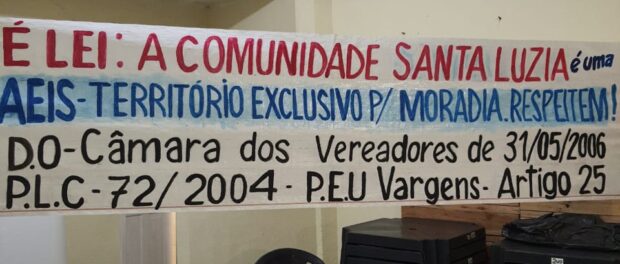

In spite of the threats of eviction, Santa Luzia was demarcated as an Area of Special Social Interest (AEIS), a designation for areas approved for preservation of affordable housing, by Rio’s City Council in 2009.

Fonseca explained how residents had been fighting for this designation for years, and that with it, “The community has to get special treatment.”

To compensate residents, the City is offering a R$400 (US$75) monthly rent voucher. However, in 2016, the average rent in Vargem Pequena, the surrounding neighborhood, was reported to be R$1198 (US$225).

City officials, without properly identifying themselves or their motives, visited the favela to push forward the threats of eviction and ask residents to fill out a registration form, according to what residents told the Public Defenders’ Office’s Land and Housing Nucleus (NUTH). However, due to the uncertainty behind the city’s intentions with the registration information, NUTH advised residents on July 7 not to sign anything until the city’s intentions are made known—and this is precisely what they have done—since the City did not permit residents to photograph documents for legal analysis.

According to public defender Susana Cadore, “We have requested that they halt the process entirely during the pandemic, since moving forward would require agglomerations. We have also requested access to the administrative process that determined the actions in the community. Since it’s an Area of Special Social Interest, any interference or eventual relocation must be thoroughly discussed with residents, something that has not taken place. We have also requested the risk reports.”

Evictions moratoria have been one of the more common public policies issued in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, globally, existing today in over half of states in the United States, in Europe, Uruguay, Mexico and Australia.

The threat of eviction constitutes yet another challenge to the residents of Rio’s favelas, as the city has registered a mortality rate from Covid-19 that ranks among the highest in the world. Favela residents, many of whom work in the informal economy, have also been hit hard by the economic impact of the pandemic.