This is our latest article on Covid-19 and its impacts on the favelas and in the series of Teach-Ins on Covid-19 in favelas.

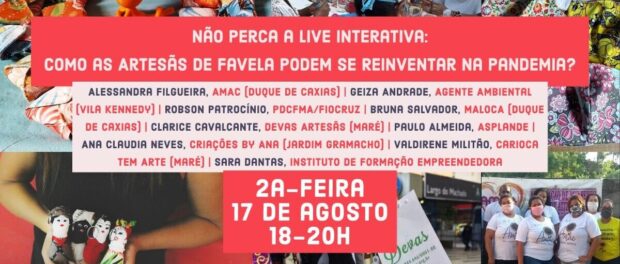

On August 17, the Sustainable Favela Network’s (SFN)* Income Generation Working Group hosted the virtual teach-in “How Can Favela Artisans Reinvent Themselves During the Pandemic?” The event, held over Zoom and broadcast live on Facebook, featured artisans, activists, and educators who discussed the challenges presented by such uncertain times, the need for adaptation, and the importance of working in networks and groups.

The discussion was moderated by Fernanda Garcia, a favela-based communicator from Complexo do Alemão. The speakers included Alessandra Filgueira, a resident of São Bento in the municipality of Duque de Caxias and member of the Association of Assertive Women with Social Commitment (AMAC); Geiza de Andrade, resident of Vila Kennedy in Bangu, Rio’s West Zone and founder of the Marias in Action Project and her own line of handiwork; Robson Patrocínio, coordinator of the Nutritional Sovereignty and Security and Solidarity Economy projects at Brazil’s national health foundation, Fiocruz; Clarice Cavalcante, founder of Devas Artisans in Nova Holanda within the Complexo da Maré; Bruna Salvador, a resident of Duque de Caxias, artisan working with recycled materials, and member of the Alternative and Organized Liberation Movement for Citizenship and Social Support (MALOCA); Paulo Almeida, a volunteer with Asplande (Support and Planning for Development) providing entrepreneurs with administrative and financial support; Ana Claudia Neves, founder of Creations by Ana and former waste picker at the Jardim Gramacho landfill; Valdirene Militão, resident of Maré, artisan who works with discarded materials, and founder of the Carioca Has Art line; and Sara Dantas, a business coach and mentor from the Institute of Entrepreneur Training.

The discussion was moderated by Fernanda Garcia, a favela-based communicator from Complexo do Alemão. The speakers included Alessandra Filgueira, a resident of São Bento in the municipality of Duque de Caxias and member of the Association of Assertive Women with Social Commitment (AMAC); Geiza de Andrade, resident of Vila Kennedy in Bangu, Rio’s West Zone and founder of the Marias in Action Project and her own line of handiwork; Robson Patrocínio, coordinator of the Nutritional Sovereignty and Security and Solidarity Economy projects at Brazil’s national health foundation, Fiocruz; Clarice Cavalcante, founder of Devas Artisans in Nova Holanda within the Complexo da Maré; Bruna Salvador, a resident of Duque de Caxias, artisan working with recycled materials, and member of the Alternative and Organized Liberation Movement for Citizenship and Social Support (MALOCA); Paulo Almeida, a volunteer with Asplande (Support and Planning for Development) providing entrepreneurs with administrative and financial support; Ana Claudia Neves, founder of Creations by Ana and former waste picker at the Jardim Gramacho landfill; Valdirene Militão, resident of Maré, artisan who works with discarded materials, and founder of the Carioca Has Art line; and Sara Dantas, a business coach and mentor from the Institute of Entrepreneur Training.

Because of the pandemic, artisans have been forced to adjust their business practices to be able to continue producing and selling their products. Additionally, as Andrade explained, the unemployment crisis has driven more favela residents to try their hand at artisanship: “Many professionals with jobs requiring physical contact became unemployed, and many of these people saw artisanship as a way to generate an income.”

For Militão, artisans are especially apt, due to the creative and innovative nature of their profession, to adjust and make the most of any situation: “In this pandemic, we either go crazy or we create.” She explained how artisans are used to finding the positive side of what most people see as entirely negative circumstances, saying that with her own work, “people think that something is trash, but I see usable material.” Salvador echoed those sentiments, saying that she “transforms trash into luxury.”

The artisans are part of the solidarity economy in Rio, and the speakers stressed the importance of how this economy focuses on directly improving the lives of those working in it. Patrocínio explained, “The solidarity economy has the person as its center. It is another mode of being, beyond commercialization.”

One particular opportunity that the pandemic has presented is a sudden boom in demand for masks. Many favela artisans, trained in sewing, began producing masks for their communities and beyond, and these have proven to be great ways for the artisans to maintain financial stability. Speaking about her own reinvention, Neves, who normally makes keychains and bags, explained, “A friend of mine told me, ‘Why don’t you start making masks?’ She helped me and I started making the masks. It was an emotional boost for me.”

One particular opportunity that the pandemic has presented is a sudden boom in demand for masks. Many favela artisans, trained in sewing, began producing masks for their communities and beyond, and these have proven to be great ways for the artisans to maintain financial stability. Speaking about her own reinvention, Neves, who normally makes keychains and bags, explained, “A friend of mine told me, ‘Why don’t you start making masks?’ She helped me and I started making the masks. It was an emotional boost for me.”

Several of the artisans have made masks at some point during the pandemic, with many of their products donated to communities in the interest of public health. Militão, for example, exchanged her masks for food that goes in packages of basic foodstuffs that are distributed to Maré residents in need.

Neves’ experience, getting help from her friend, also reflects another key theme that surfaced during the discussion: networks of support. The speakers widely praised the crucial role that these support groups play—in normal times, educating artisans to realize effective business practices, and during the pandemic, helping them adjust.

“When we are in a network, it means that we have support. It means that what I don’t know, somebody else knows,” Dantas says. “Together, we are much stronger.”

Speaking about his work with Asplande, Almeida stated that, thanks to the organization and its volunteers, “The women are able to put their skills to work remotely” during the pandemic. Describing Asplande’s role in helping artisans develop sustainable entrepreneurial plans and maintain digital platforms, he again praised the importance of networks, saying, “if they move together, everybody will achieve a better result.”

Overall, the artisans spoke highly of the role of their crafts in improving their lives, both financially and otherwise. Cavalcanti noted that as artisans learn and develop through the networks and courses available to them, she sees that they become “more confident in themselves, believe in themselves.”

Similarly, as Salvador, who taught herself artisanal techniques through YouTube videos, attested, “I haven’t even been an artisan for two years, but it has been a really awesome experience in my life.”

Watch the discussion here:

*The Sustainable Favela Network (SFN) and RioOnWatch are both projects of the NGO Catalytic Communities (CatComm). The SFN is supported by the Heinrich Böll Foundation Brazil.