This is our latest article on Covid-19 and its impacts on the favelas and part of our series covering 2020’s Black July.

On July 29, as part of the series of events for the 5th edition of Black July (Julho Negro), a livestreamed debate was held entitled “Black Women Analyze State Violence.” It featured four mothers that had in common not only the murder and violence suffered by their children, but also the fact that they courageously continue to denounce the state violence that targets young black people in Brazil.

The discussion touched on striking topics—like the torture that occurs in Brazil’s juvenile detention system DEGASE (Department of General Socio-Educational Action), police killings, military intervention, and police training—and was mediated by researchers Luciane Rocha and Rachel Barros. The event included the participation of Deize Carvalho, founder of the Nucleus of Victim Mothers of Pavão-Pavãozinho and Cantagalo; Irone Santiago, a social activist with Redes da Maré; Márcia Jacintho, an activist with the Network of Communities and Movements Against Violence; and Zoraide Vidal, a lawyer whose daughter, a police officer, was killed in the line of duty.

Irone Santiago—whose son Vitor Santiago became paraplegic and was mutilated by police gunshots on his way home after a night out with friends—explained how the mothers of victims of state violence are forced to take justice into their own hands. According to Santiago, this job should be done by the state itself. “At the beginning of my fight…each place I went, I was called ‘crazy.’ Everyone said I was going to achieve nothing. I didn’t believe in people…and I still kept fighting. But today I fight differently, because I felt a lot of hatred towards the Military Police. Today, I am looking to get treatment for myself, because police officers also have mothers. It is very difficult to empathize, to put yourself in other people’s shoes and understand them. When people say that my case is different because my son is alive, I don’t accept that. It is a [human rights] violation, like any other,” she said.

Santiago’s story is similar to those shared by other participants of the discussion. For years, these mothers had to gather, on their own, the means to continue fighting for justice for their children. During the debate, the mediators showed videos of the various mothers calling for justice on the streets. One of those images was of Carvalho in front of the Court of Justice of Rio de Janeiro, demanding answers about the case of her son Andreu Luiz Carvalho, who was tortured for an hour and killed by six policemen inside DEGASE. She blames corporatism within the state for the difficulty in moving her son’s case forward and holding perpetrators accountable.

“When these hideous crimes happen, they try to hide evidence of the crime. In my son’s case, the forensic doctor was absent throughout the process. My son had deep cuts, but it wasn’t clear how they were made. This is corporatism, which doesn’t condemn its agents, just like in the case of Maicon, a two-year-old child killed by a policeman, in which the case was closed after it was claimed [by police] as an act of legitimate defense.”

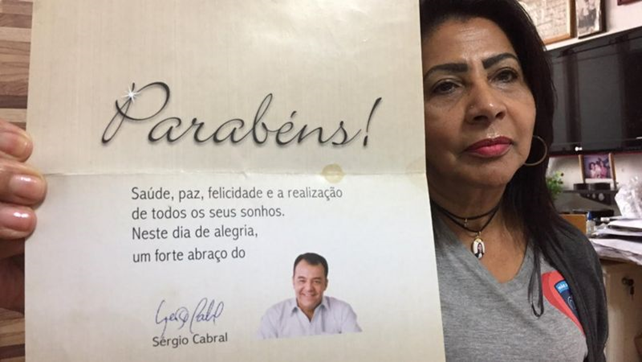

Unlike the children’s game “cops and robbers,” in real life, the good guys and bad guys are not so obvious. Vidal, whose pregnant daughter Ludmila Fernandes Fragoso was tortured and charred in a robbery in Duque de Caxias after she was discovered to be a police officer, said, “I had no help from anyone, not even the State. The State is so disorganized, even with their own. A month after Ludmila died, they sent me a birthday card! It’s not just in the favela, they don’t bother with anyone,” said Vidal, who lamented the precarious conditions at police stations. She added, “Ludmila used to take in… [her own] reams of paper to be able to provide good service. We don’t want to blame individual officers. It is the government’s fault.”

The mothers agreed that this violence can be solved through public programs that can bring hope to young people by offering them an education in order to make drug trafficking less appealing as a source of income.

“I’m not about violence, but peace. We, black people, can’t go far with war. The only weapon that we have is education, by encouraging our children to study. It’s a struggle of knowledge, so that we can talk as equals,” explained Vidal.

Carvalho added, “Once you go through the prison system, you’re a criminal forever. Instead of providing vocational training, socio-cultural activities…We have a bourgeois elite that trivializes and devalues violence. The state doesn’t care about the favelado or the policeman sent to the favela.” She concluded, “No mother raises a child to be a criminal. No child is raised with a rifle inside the womb. It’s the state that puts forward this weapon of violence.”