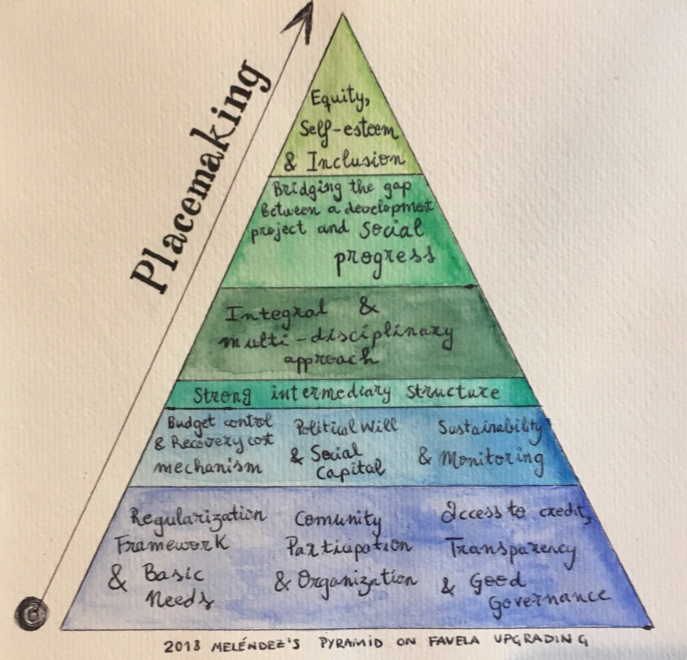

This is the second article in a six-part series on the application of Meléndez’s Pyramid for Favela Upgrading to the city of Rio de Janeiro and its favelas. This pyramidal concept was conceived by the author of this series as a proposed methodology to achieve more coherent and sustainable results in favela upgrading. Inspired by Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, the pyramid consists of ten blocks, each representing a group of indispensable elements. Essentially based on multidimensionality, interdependence, and simultaneity, the pyramid addresses the physical, political, economic, social, cultural, and psycho-emotional aspects of favelas.

This second article addresses the importance of regularization, basic service provision, and community participation in favela upgrading. Read the full series here.

At the bottom of Meléndez’s Pyramid for Favela Upgrading are the quintessential, baseline needs for the development of Rio’s favelas. These start with regularization and the guarantee of basic needs. Together, as complementary elements, land regularization provides access to city services and privileges, setting favela residents on a more equal footing with regards to other citizens.

Regularization and Basic Needs

Most favela residents live without secure tenure, thus experiencing a lingering threat by eviction, even over generations. Therefore, in order for favela upgrading to be sustainable, regularization is essential. Nonetheless, tenure regularization can lead to real estate speculation, gentrification, and market displacement—presenting a dilemma between satisfying the need for formalization of land rights, and the need to prevent displacement.

Legal instruments such as individual titling through adverse possession have proven inadequate for regularizing Rio de Janeiro favelas when residents’ goal is to remain in their homes and communities, due to their fostering the new risks of real estate speculation and gentrification. And state-provided concession of use rights on favelas located on public lands have proven unstable, with the famous example of Vila Autódromo being evicted despite 99-year concession of use titles. Another, promising option, however, is regularization through collective adverse possession, though there are few cases to speak of to date.

Of note, Brazil has a special legal designation called a Zone of Special Social Interest (ZEIS). This instrument allows favelas demarcated as ZEIS to be regulated according to a more flexible set of zoning rules, and guarantees they be recognized and preserved as zones of affordable housing. This tool thus generally allows for innovative planning regulations that favor favela upgrades and permanence.

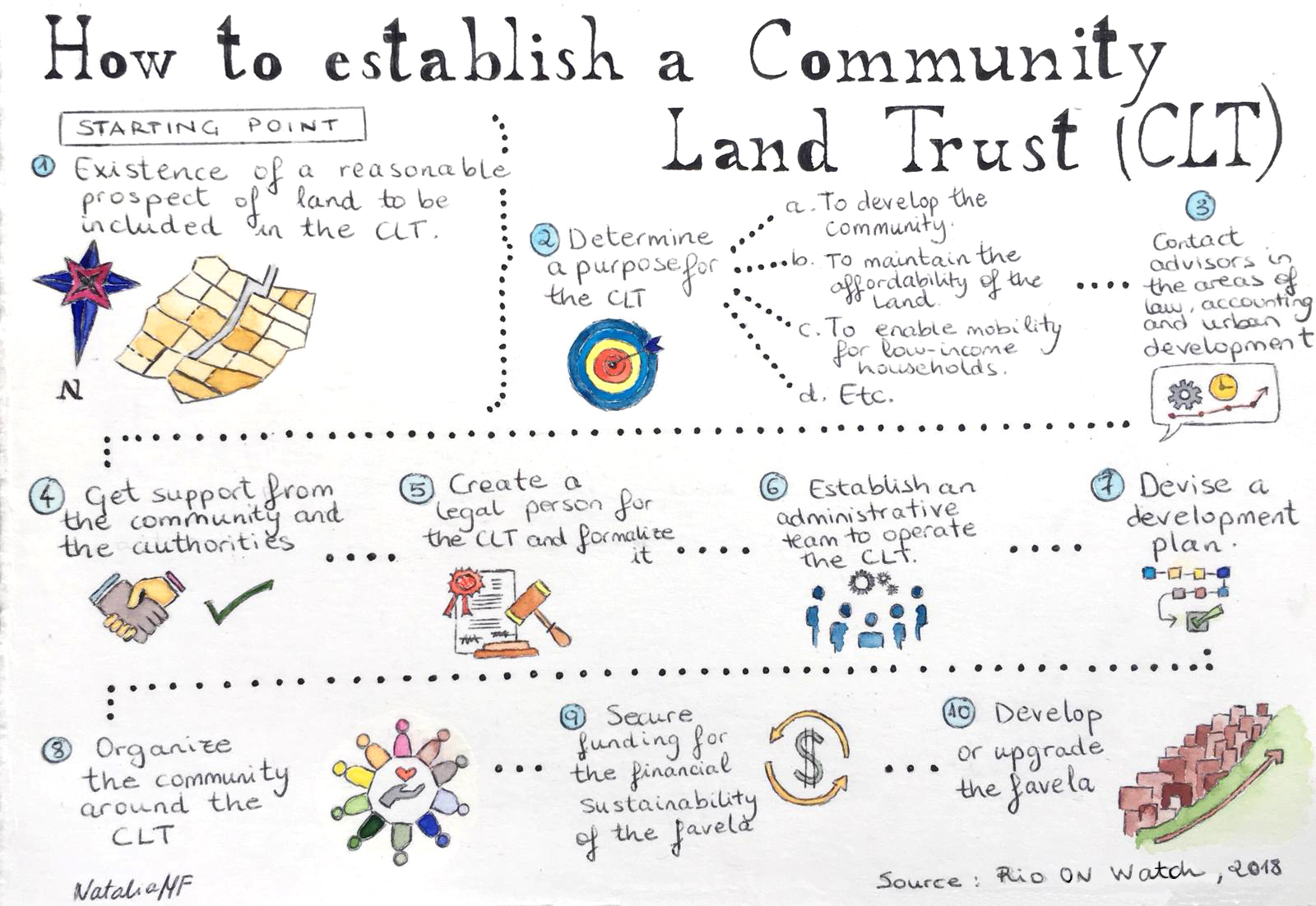

Building on the lessons produced through these various existing approaches, there is now a movement in Brazil to allow for the establishment of Favela Community Land Trusts (CLT) as has been done to great avail in San Juan, Puerto Rico. If introduced, the Favela CLT will bring a tailored approach to titling and community development in the favelas benefited, while providing greater equity and stability broadly speaking to Rio’s housing stock. A CLT is a form of collectively-owned land seeking to guarantee rights and tenure security for low- and moderate-income households. The first prerequisite for the establishment of a Favela CLT is land regularization. The community-managed CLT becomes the legal entity which owns and administers the land, including, if it chooses to do so, setting ceilings on property value. The land regularization includes both collective land ownership and individual surface rights. This modality allows for a healthy balance between private property and secure land rights. Within a CLT framework, land may be acquired through purchase, sale, or donation.

Guaranteeing affordable housing for perpetuity, the CLT makes it possible for residents to stay in their neighborhoods with little risk of land speculation, gentrification or foreclosure. Different from individual titling, CLT-owned land is permanently taken off the market. The rationale behind the CLT model is that favelas do not operate by strict market logic, producing non-monetizable assets such as mutual aid, cultural production, a sense of belonging, and others, that go unrecognized by the market yet are valuable to residents, and which is why so many favela residents choose to stay in their neighborhoods even as they could afford to leave.

Within the Rio context, the CLT presents itself as a hopeful prospect, notwithstanding some limitations. A model self-built public housing project, Conjunto Esperança, is now exploring establishing their land rights through a CLT that will be adapted to their particular needs. Meanwhile, the favela of Trapicheiros has been taking steps to become the city’s first pilot Favela-CLT.

Collective titling is not new to Brazil, where indigenous communities and quilombo communities comprised of descendants of enslaved peoples have their collective land rights recognized. Article 68 of Brazil’s Constitution grants individuals with quilombola origins the right to receive the title to such lands. When applied to an urban context, quilombos, together with Favela CLTs, offer inspiration for respectful recognition of the collective values developed in Rio’s favelas.

Community Participation and Organization

Continuing with our approach, the bottom center of our pyramid underlines the imperative of community participation and organization. For favela upgrading to yield effective and sustainable results, residents must own and “invent their own spaces” at all stages of the upgrading cycle: from design to evaluation. Ideally, a subsidiarity approach would be adopted, with residents, external collaborators, volunteers, multidisciplinary practitioners, researchers and—need it be—donors co-designing on an equal footing, according to their needs, interests and skills. This is in contrast to what happened during the high-activity months of the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) in the favelas of Alemão, for example, when residents were “consulted” only to have their needs ignored, resulting in a cable car rather than basic sanitation. In favela upgrading there are no shortcuts to quality results, and upgrading can only succeed when a synergy between people, their needs and their inhabited places are prioritized, listened to, and ultimately realized.

Community participation and organization renders the identification of priorities and needs easier, and optimizes the use of resources. Moreover, it has also been shown to reduce costs due to residents’ own dedication of labor and materials, which can help revitalize local economies.

By and large, favelas pose a great challenge to planners and decision-makers due to their intricate, unique forms, social implications and proven impact on the economy and evolution of cities. How better to reduce this challenge than by giving more agency to those who best know the favelas—their residents? Resident control, beyond consultation, is paramount in favela upgrading. One of the few Rio de Janeiro examples of full citizen control over the planning process are the self-built public housing projects of the Minha Casa Minha Vida-Entidades Program (MCMV-EN) of which Conjunto Esperança is one example.

For their part, outsiders to favelas must transcend the notion that they know what is best for communities. A program that does not allow for solid and meaningful community control undermines favela residents as “sub-citizens.” A paternalistic approach to upgrading is neither constructive nor sustainable. Besides, inclusive measures increase community pride, sense of belonging, and citizenship.

Community control and engagement can be complemented through a self-help model, in which the funding entity acts mainly as a provider and technical ally, while much of the work is performed or coordinated by the community. Already inherent in the Brazilian tradition of mutirão, a self-help model overcomes paternalism and guarantees community control over outcomes, empowering residents in their relationship with the larger city. Moreover, when residents decide on and implement measures, needs are assessed more accurately and so results tend to be more cost-effective. The leaking of public resources due to corruption can also be reduced.

In Rio, the self-help model already applies to most favela homes, and, in some cases, to public infrastructure (e.g., Asa Branca’s sewerage system and Favela da Formiga’s water-provision system). Favela communities in Rio have traditionally responded themselves to the failure of authorities to meet needs that are in the public interest. Very often, favela residents provide what should be public services such as transportation, schools, nurseries, or medical centers. Vila Autódromo’s Popular Plan is one example of self-planning in the absence of the state, which questions the efficiency and validity of top-down approaches to community development.

An added value of community participation is the way it intertwines with respect for local culture and traditions. Localized approaches enable residents of each favela to enhance their own specific identity—which in turn contributes to the sustainability, cohesion and self-esteem of the community.

This is the second article in a six-part series.

Natalia Meléndez Fuentes is an MSc candidate in Building and Urban Design in Development at the Bartlett Development Planning Unit at University College London. Her research looks at urban informality learnings, the psycho-emotional elements of favelas and favela upgrading, mainly in Latin America, and how to bring these to the fore.