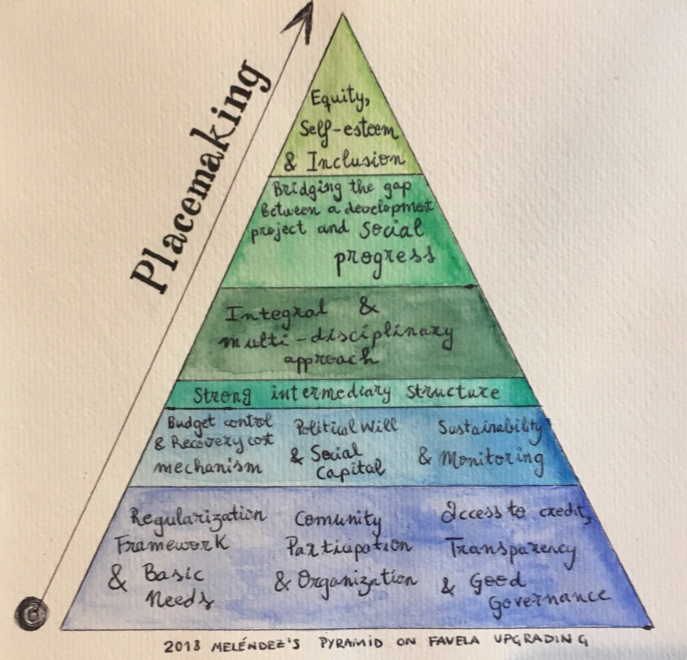

This is the third article in a six-part series on the application of Meléndez’s Pyramid for Favela Upgrading to the city of Rio de Janeiro and its favelas. This pyramidal concept was conceived by the author of this series as a proposed methodology to achieve more coherent and sustainable results in favela upgrading. Inspired by Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, the pyramid consists of ten blocks, each representing a group of indispensable elements. Essentially based on multidimensionality, interdependence, and simultaneity, the pyramid addresses the physical, political, economic, social, cultural, and psycho-emotional aspects of favelas.

This second article addresses the importance of access to credit, transparency, governability, budget control, and cost recovery. Read the full series here.

Access to credit, transparency, and good governance are the elements that constitute the bottom-right block of the Pyramid for Favela Upgrading. Together with regularization, basic services and community participation and organization, these constitute the foundation for favela upgrading programs to build upon each favela’s strategies, projects and initiatives. In this regard, it is important to emphasize that favela upgrading (especially exogenous programs—those driven by external criteria) should not try to build from scratch, but rather learn from and with favela residents and on each favela’s own terms and meanings. This pyramid rejects the mainstream approach to upgrading that imposes “development” conditionalities, and through that, exogenous conceptions of development.

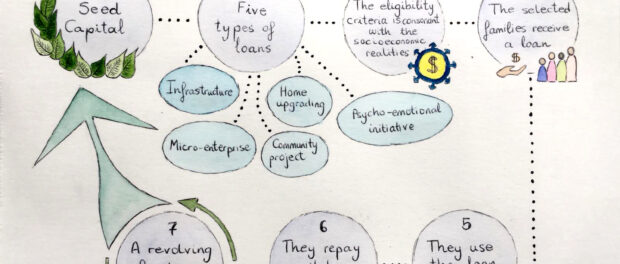

Access to credit is the most intuitive enabler for upgrading works to start. But as people in the lowest income bracket often struggle to meet the eligibility criteria for subsidies or loans, it is crucial for financial structures to be inclusive. The Swedish International Development Agency (Sida) conceived a model to reverse this trend: it applies different selection criteria that account for the socioeconomic realities of each group. Since traditional methods of financing tend to be inaccessible to favela residents, the funding entity, whether government or private, must operate as an inclusive small-scale lender. This type of financial model could prevent residents from resorting to informal up-front or installment payments, which usually imply fluctuating or high interest rates.

Drawing from the Sida model, favela upgrading must adopt a financial model that is sustainable and transparent. Along this line, different types of loans should be offered (e.g., for infrastructure, home upgrading, micro-enterprise, community projects, and cultural or psycho-emotional initiatives). Ideally, a seed investment that is eventually paid back to the lending entity would enable the community to generate its own revolving fund in which families receive a loan, use it to cover their needs, and then repay it through installments that match their financial capacity.

This model aims to solve the “loan v. subsidy” debate that is so widely pondered in the development field. On the one hand, subsidies can build an unrealistic perception of the cost of materials for development, potentially limiting personal and community autonomy. On the other, loans—if unchecked and unfriendly towards borrowers—can impose a life beyond people’s means and future indebtedness. This model offers an alternative: a revolving fund that, once the seed funding is paid back, is autonomously controlled by the community. This fund would give access to small loans that respond to people’s and the community’s financial capacities and needs. Moreover, a revolving fund yields autonomy from partisan politics and from non-pluriverse development.

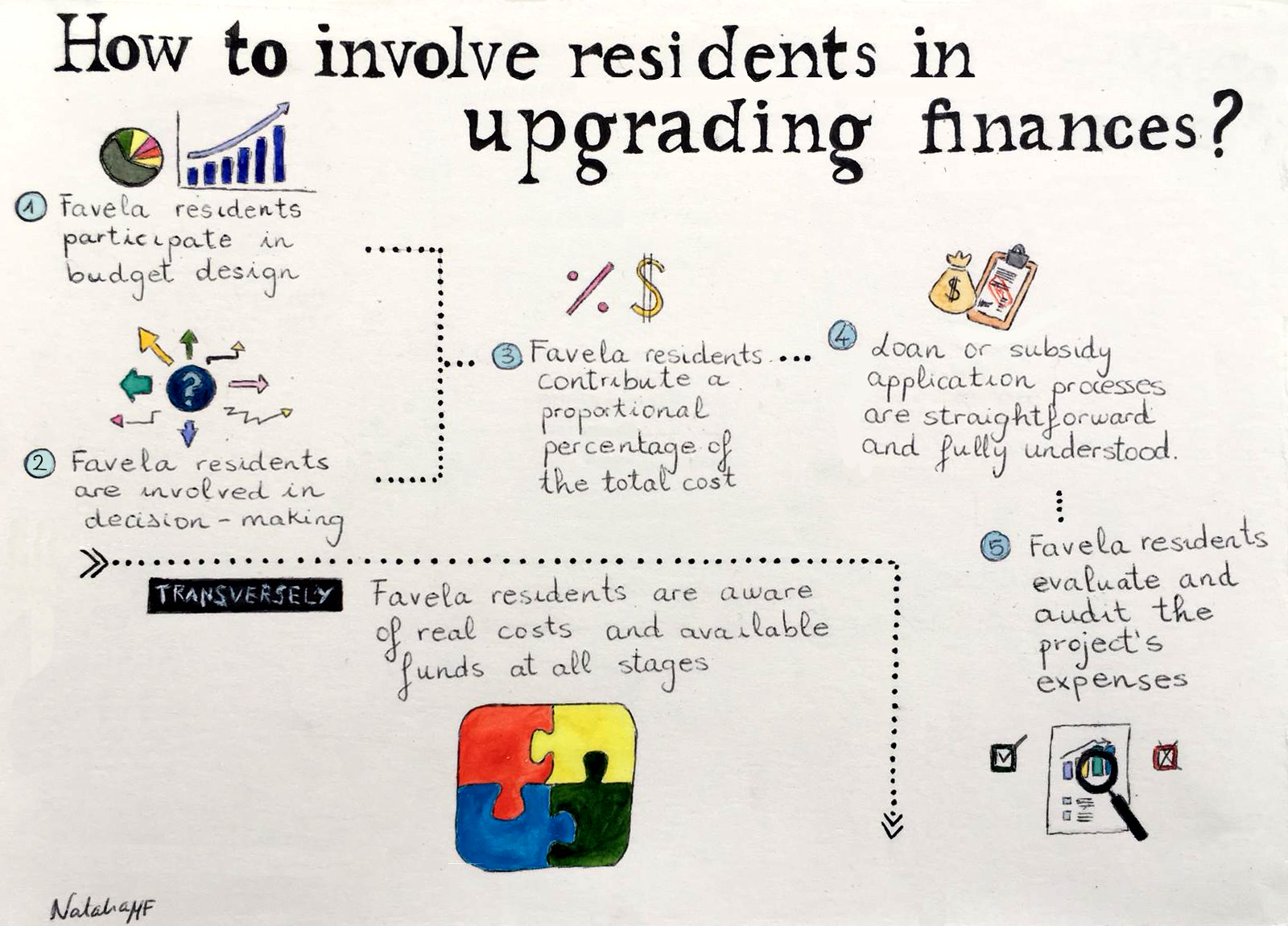

For financing structures to be efficient, transparency is a further and paramount element that ensures cost-effectiveness and heals the relationship between communities and authorities by building trust. This is most evident when the participation element allows for communities to be aware of, control, and audit the financial entity (be it a community-based or external body). Within a transparency logic, all procedures—especially loan application schemes—are straightforward and fully understood by residents, avoiding jargon. With regard to project financing, enabling residents to partake in budget design, monitoring, and evaluation builds trust, capacity, and narrative-shifting.

In this line, transparency is intrinsically related to good governance. Brazil at large is affected by a conspicuous governability deficit. This includes weak institutions, deficient mechanisms for citizen participation and accountability, patronage, clientelistic relationships, and corruption, among other challenges. Autonomous financial accessibility through a community-managed revolving fund would offer an opportunity for favela upgrading unhindered by this broader context. This sociopolitical background also illustrates why upgrading should also contemplate institutional development, including capacity-building of external actors who work with communities and grassroots organizations. This could also contribute to reconciliation in communities across the country where trust has been broken in the past and provide further support to favelas through connections and resources at multiple scales.

In learning from communities, local authorities would increase their governability. In Brazil, unfulfilled political promises pose a real danger. With voting compulsory, in Rio de Janeiro, where 23% of the population lives in favelas, favela residents represent nearly ¼ of the electorate. Many promises went unfulfilled during former Mayor Eduardo Paes’ term, as with the striking example of the Morar Carioca program. The current Marcello Crivella administration (2017-2020) has yet to materialize his campaign pledges. Local authorities should start leveraging their privileged positions to comprehend and listen to communities and advance in their compliance with the 1990 Organic Municipal Law and with Articles 182 and 183 of the Brazilian Constitution. These pieces of legislation require the provision of adequate basic services, infrastructure, and upgrading to favelas that need them.

It is noteworthy that Brazil, and Rio in particular, are increasingly seeing more elected representatives from favelas. This is a truly significant step for a change in narratives, reflecting growing awareness about favela life: including communities’ actual situations and needs, their actions and social capital, and enormous value. This trend has the power to counteract the stigmatizing narratives about favelas broadcast historically by mainstream Brazilian media.

A closer and more open relationship between communities, authorities, and funding entities leads to two invaluable scenarios. First, communities begin to grasp the role, real limitations and resources of external entities and appropriate the financial process through a grassroots-managed revolving fund. Second, authorities learn to listen, work with, support, and acknowledge favela residents.

Moving upward in the pyramid, the next block on the left represents budget control and cost recovery mechanisms. As pointed out by urban planners Ivo Imparato and Jeff Ruster, keeping upgrading actions within budget ensures that upgrading does not stall due to a “sudden” lack of funding. For its part, cost recovery—which is an essential part of the revolving fund—supports independence on the part of communities realizing favela upgrading.

How can one translate budget control and cost recovery into action? By informing and including communities at all times. Residents are informed when they are aware of real costs and available funds at all stages—overcoming financial obscurantism and, possibly, micro-corruption in urban development. Taking further steps in transparency-building, residents must be involved in decision-making and could, if appropriate and fair, contribute a proportional percentage of the total cost of community projects, thus furthering appropriation and engagement. What is more, cost recovery is further guaranteed when residents conduct most of the upgrading works themselves, because they control and ensure affordable planning, materials, expenditure and human resources.

A more inclusive, participatory and transparent approach to upgrading finances will bring heightened economic gains to the favelas and to Rio and Brazil at large. There is no question that favelas make important contributions to local and national socio-economies (both formally and informally). Inclusive and autonomous finances in favela upgrading would work toward reciprocality and away from exclusion and profiteering in the financial realm.

This is the third article in a six-part series.

Natalia Meléndez Fuentes is an MSc candidate in Building and Urban Design in Development at the Bartlett Development Planning Unit at University College London. Her research looks at urban informality learnings, the psycho-emotional elements of favelas and favela upgrading, mainly in Latin America, and how to bring these to the fore.