This is our latest article on Covid-19 and its impacts on the favelas and the first of a two-part report analyzing the inequality in the Covid-19 case fatality rate in two different neighborhoods of Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone, Barra da Tijuca and Campo Grande. The article was written by members of the West Zone Solidarity Web.* For Part II, click here.

This first installment presents a brief comparative history between the case fatality rate of Covid-19 in Barra da Tijuca and Campo Grande, highlighting inequity in the health system and the different racial profiles of the neighborhoods.

When the numbers become friendly faces, neighbors, and relatives, they reveal the sad inequality to which we are subjected on the periphery of the world, which is largely the result of structural racism. At least three central inequities intertwine in the context of Covid-19, all interrelated. One has to do with the tangible risk of death, the second with access to public policies—for health and for other issues that guarantee dignity—and the third, with access to high-quality and contextualized data. This last injustice includes not only underreporting but also choices about which data to publish, as certain numbers can give visibility to other inequalities.

To the extent that they overlap in the poorest and most populous part of the city of Rio de Janeiro, these inequities have exacerbated a morbid pattern in the exercise of government power, which sometimes kills the poor, black, peripheral population and sometimes lets them die. That is evident by looking at the case of Campo Grande, a neighborhood of more than 300,000 inhabitants in the West Zone, which has become the epicenter of Covid-19’s fatalities in the city.

Members of the West Zone Solidarity Web keep track of information on deaths related to potential infection by the novel coronavirus with the new Rio city government’s Covid-19 Dashboard produced by the city government. In late March, the West Zone only appeared on the map, with confirmed cases of Covid-19, because of Barra da Tijuca—an affluent neighborhood within the West Zone. In those days, it ranked first in the city in number of notifications. All of the other neighborhoods that led in case counts were located in the city’s South Zone. Although it lies in the West Zone, Barra da Tijuca is aligned with the South Zone in demographic characteristics. High infection rates were concentrated in the municipality’s most expensive neighborhoods, by square meter. These are areas of high buying power, with mostly white residents, whose right to the city—and to life—is guaranteed by the State through public policies. The data that show the disease began spreading in these neighborhoods may also have been affected by the mere access to tests; as we will see later, this level of access is part of the same context of inequality.

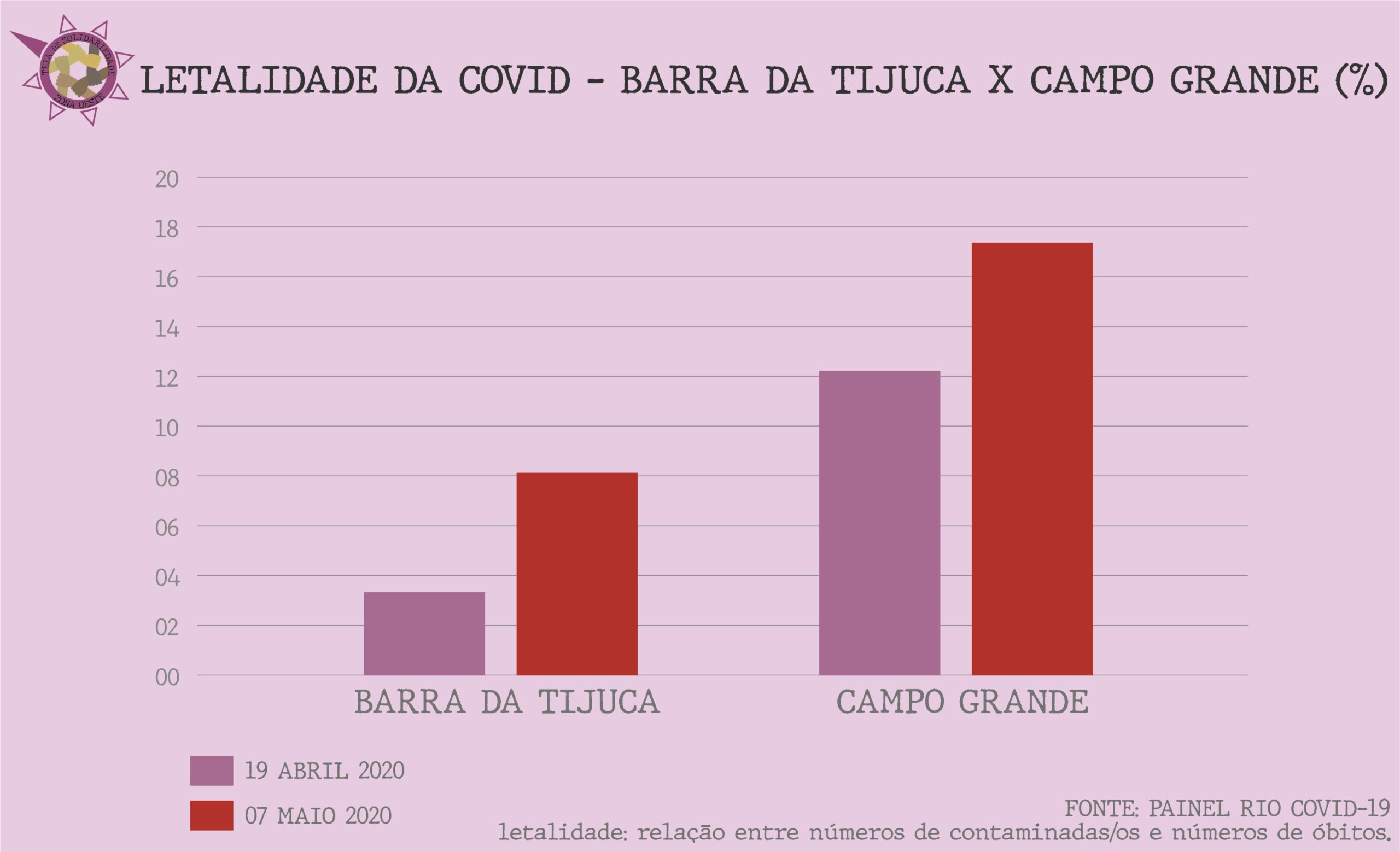

On April 19, with a much smaller number of reported cases, Campo Grande, a low-income neighborhood, began to emerge in the ranking of deaths. While the upscale neighborhood of Barra da Tijuca had 246 reported infections and 11 deaths (4.47%), the low-income neighborhood of Campo Grande had 144 reported infections and 20 deaths (13.89%), which means that for every 100 patients in Campo Grande, 14 died, while in Barra, four did. Eighteen days after this first observation, on May 7, Barra da Tijuca had a case fatality rate of 8.33%, while in Campo Grande, the rate of infected people who died reached 17.8% (see infographic above). On July 6, the city’s reporting dashboard included Campo Grande with 2,261 confirmed cases and 335 deaths (14.81%) and Barra da Tijuca with 2,472 cases and 141 deaths (5.7%). This means that by early July, according to the city’s own count, residents of Campo Grande were 2.5 times more likely to die from the disease than residents of Barra da Tijuca.

We know through experience that underreporting, both of cases and deaths, is likely hiding proportions that are even more alarming. The fact that we know stories of our neighbors who did not get health care and some who died at home, causing pain to multiply around us, compels us to demand that any measures taken in this pandemic consider these inequalities of access. It is quite evident that this difference in case fatality rate has to do with the greater access that residents of Barra da Tijuca have to the health and emergency systems confronting Covid-19, in addition to better conditions for self-care. For this reason, we argue that the government should prioritize better conditions for physical distancing and better access to health for low-income neighborhoods in the West Zone.

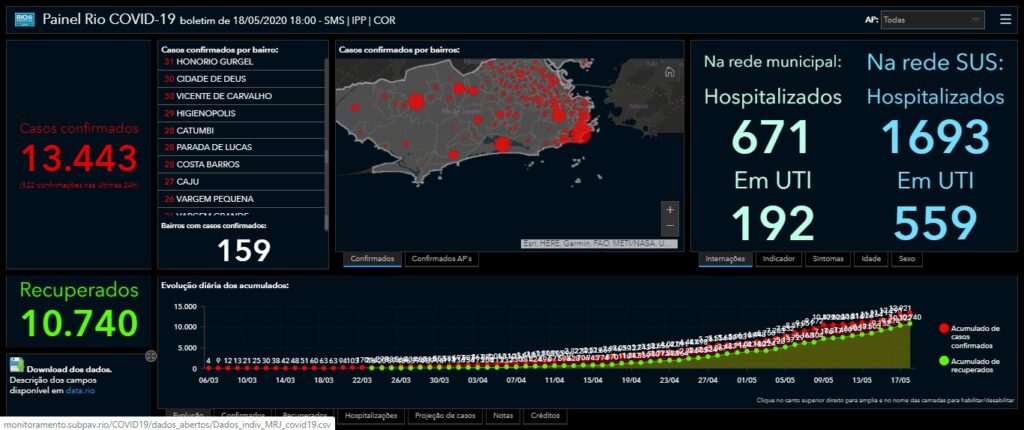

Whether by giving a racial portrait of the case fatality rate of the disease by region of the city—as Barra da Tijuca is 87.59% white and Campo Grande is 54.37% black and brown—or by not defining the rates of illness, these figures demonstrate inequality. The lack of availability of clinical tests or basic health facilities shows a lack of access to public health capacity as a very evident example of State policy. The lack of transparency about these statistics reached a climax on May 18, when the Rio city government’s Covid Dashboard halted publication of data on overall deaths in the city, disclosing only those reported by neighborhood, which prevented monitoring the case fatality rate by neighborhood.

On May 25th, a preliminary decision by the Court of Justice obtained by the Rio de Janeiro Public Defender’s Office and Public Prosecutor’s Office forced the city to return to reporting the numbers, highlighting the death count according to hospitals. However, currently, the dashboard shows the neighborhoods in alphabetical order and no longer ordered by case count, making it difficult to understand where there are more cases and, consequently, greater risks of contagion.

When looking at the data about the progression and mortality of the pandemic in a consistent and comparative way, the logic of the necropolitics—the politics of deciding those who die and those who live—is widely visible in Brazil. And it only amplifies the denunciation of social abysses and the structural marginalization of millions of people who are in large part black and Afro-descendant. These are modern consequences of the great human tragedy of the enslavement process, experienced both on the peripheries of the city of Rio de Janeiro and in countries like the United States. There is no surprise, therefore, in the government’s negligence in the face of a completely foreseeable tragedy.

The arrival of the virus in Brazil filled public discourse with one of the cruelest versions of structural racism, diffused throughout Brazilian institutions: the necropolitics of “let them die,” showing that the political, economic and ideological choices of governments, as they use violence and keep inequalities invisible, have material implications for the lives and bodies of racialized groups in this country.

The interpretation of data from healthcare policies in this pandemic highlights resource gaps and choices that have been made in allocating emergency public equipment. It is necessary to understand that expanding the reaches of basic and specialized health and social protection policies is a fundamental step to reduce social inequalities and injustices, especially for the preservation of lives.

Examining this reality, in the context of a pandemic and the distribution of emergency basic income, means reflecting on the disease’s impacts on the scope of care for vulnerable populations. In other words, in addition to layers of already existing inequalities and oppressions, one more is added at this moment: the trajectory of the resources that have been made available for the prevention and treatment of Covid-19.

Although preexisting surveys and studies pointed out that peripheral neighborhoods have the greatest risk of accelerating the exponential growth of infections, the government did not do anything based on those data. To illustrate this point, suffice it to say that the first field hospital in the city was installed in Leblon, a neighborhood that boasts the most expensive square meter of real estate in the country—and among the most expensive in the world.

This article is the first of a two-part report analyzing the disparity between the case fatality rate of Covid-19 in two neighborhoods in the West Zone: Barra da Tijuca and Campo Grande. The second installment analyzes a series of statistics—which allow the examination of other structural inequalities—and a lack of other statistics, which prevents the general population from having a clear view of its local reality in the face of the pandemic. For Part II, click here.

*The West Zone Solidarity Web is a union of collectives and institutions in the West Zone that raise donations for some neighborhoods where their political performances take place. The Popular Collective of Women of the West Zone, the Institute of Human Formation and Popular Education (IFHEP), the Piracema Collective, the Caboclas Collective, Mulheres de Pedra, and institutions such as the Angelica Goulart Foundation and the Plano Popular das Vargens joined together to seek donations for the neighborhoods of Sepetiba, Santa Cruz, Campo Grande/Bosque dos Caboclos, Pedra de Guaratiba, and Vargem Grande.

Ana Alvarenga de Castro is an agronomist with a PhD in Gender and Agriculture at the Humboldt University of Berlin and a contributor to the West Zone Solidarity Web. She currently researches the dimensions of labor, land, and food in dispute in the context of socio-environmental conflicts in Latin America.

Camila Nobrega is a journalist and researcher raised in Vila Isabel and currently a doctoral student in Political Science at the Free University of Berlin. Camila works primarily with themes related to socio-environmental justice, Latin American feminisms, and the democratization of media, connecting journalism, activism, and research.

Caroline Santana is a doctoral student in Social Work at UFRJ, a Master in Urban and Regional Planning from IPPUR/UFRJ, a member of the Women’s Circle of the Rio de Janeiro Urban Agriculture Network, and an activist from the Group to Combat Racism in the Baixada Fluminense.

Marina Ribeiro is an educator, a social scientist with FIC-FEUC, an anti-racist researcher and activist, a member of the Popular Collective of Women of the West Zone and the Articulation Web for West Zone Solidarity, and a founder and general coordinator for the Institute of Human Formation and Popular Education (IFHEP).

Rosineide Freitas is born, raised, and still a resident of Campo Grande, a professor at UERJ, and member of the Rio de Janeiro Regional Board of ANDES-SN, Popular Collective of Women of the West Zone, State Forum of Black Women Rio de Janeiro and Collegiate of Civil Society of the Marielle Franco Permanent Dialogue Forum of ALERJ.

Silvia Baptista is a black woman of quilombola origin raised in Vargens, an educator, and a doctoral student in urban planning at IPPUR/UFRJ.

Infographics by Poliana Monteiro.