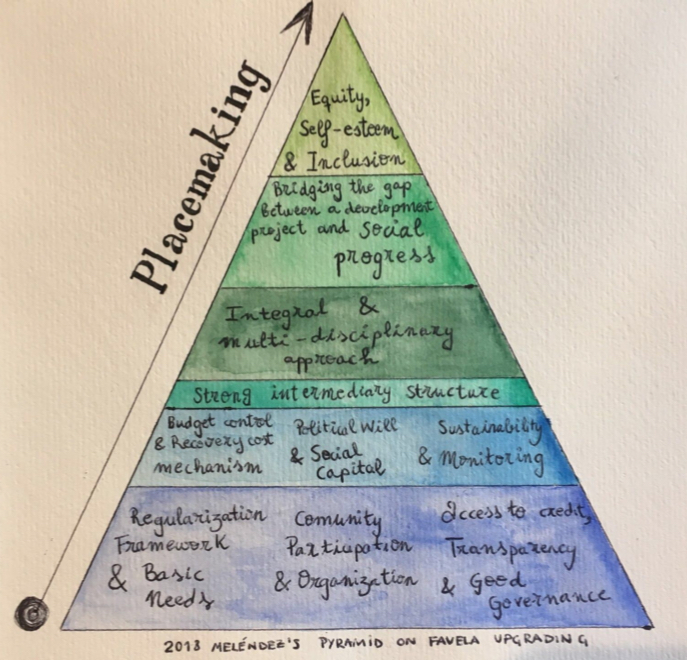

This is the fifth article in a six-part series on the application of Meléndez’s Pyramid for Favela Upgrading to the city of Rio de Janeiro and its favelas. This pyramidal concept was conceived by the author of this series in order to achieve more coherent and sustainable results in favela upgrading. Inspired by Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, the pyramid consists of ten blocks, each representing a group of indispensable elements. Based on multidimensionality, interdependence, and simultaneity, the pyramid addresses the physical, political, economic, social, cultural, and psycho-emotional aspects of favelas.

This fifth article addresses the importance of a strong intermediary structure and integral multidisciplinary approach. Read the full series here.

The middle levels of the Pyramid for Favela Upgrading make reference to two additional elements to promote placemaking in favelas. The first is the introduction of a strong intermediary structure that convenes all stakeholders to form a basis of transparency. The second is an integral multidisciplinary approach in order to ensure that progress in some areas is not undermined by neglect of others.

An intermediary structure, as discussed here, is recommended for upgrading projects in which external actors are involved, such as those that are municipal, national, or international in scope. It might take the shape of a forum or a temporal entity that meets regularly or holds several key meetings over the course of the upgrading process and is designed to guarantee expression to the diverse stakeholders involved in upgrading, such as residents, community business owners, grassroots leaders, public authorities, private companies, landowners, donors and NGOs. If, however, upgrading is initiated and run by the community alone, such a structure may be unnecessary if the community already has an autonomous and accountable process of managing their resources.

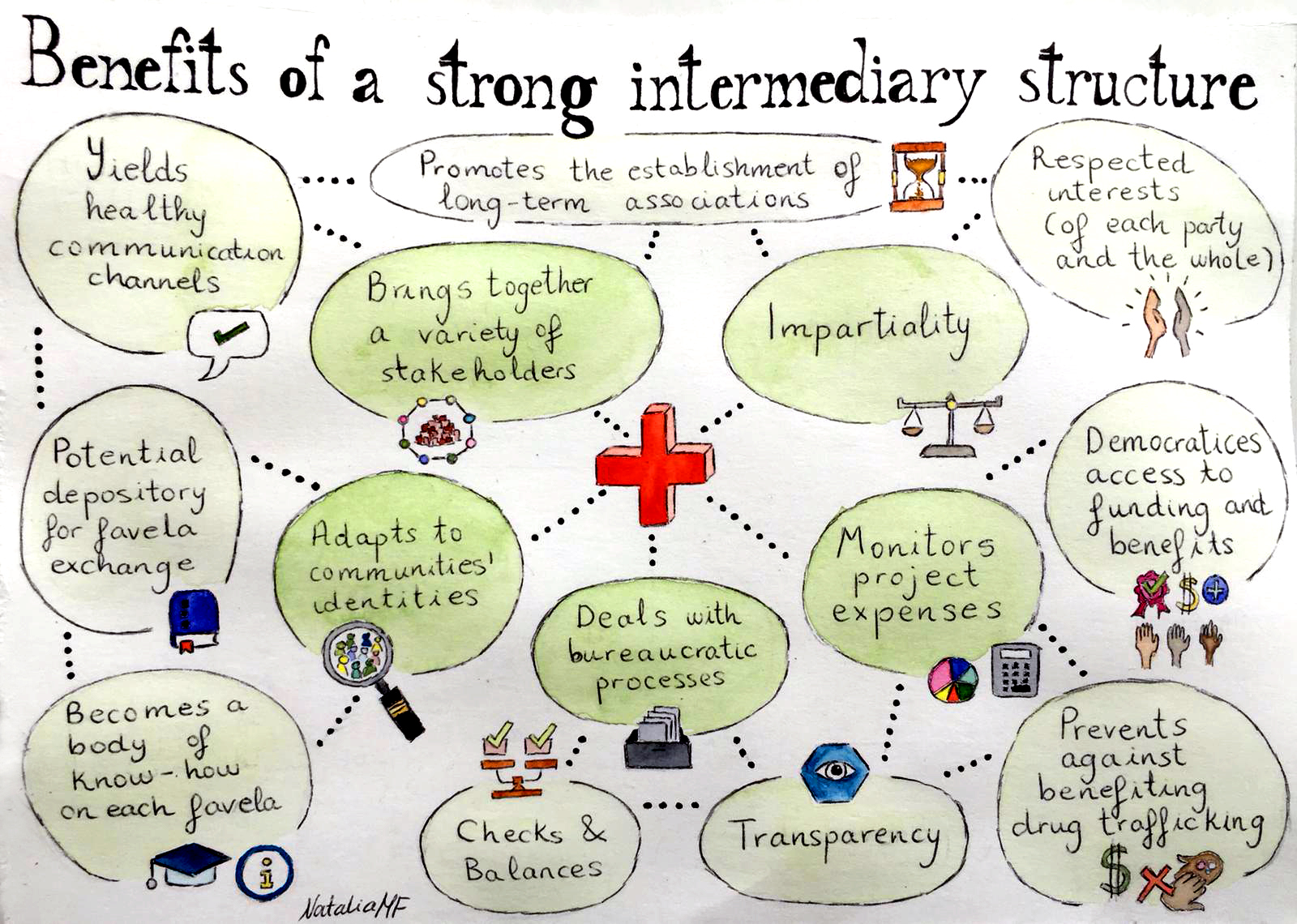

Given that favela upgrading occurs within the context of the housing market, this intermediary space is created so that the interests of traditionally powerful actors do not dominate the process. The intermediary structure is expected to ensure strategic partnerships and healthy communication channels that protect the interests of each party individually and of all parts together.

Ideally, this intermediary structure supports the community in monitoring upgrading expenses, ensuring that funding is strategically allocated, and that actions meet the community’s actual needs in a way which democratizes access to funding and benefits. Moreover, this structure helps navigate bureaucratic hurdles. In the event that the program has provided for a revolving fund, the intermediary structure could be financed by or supported through it.

Building on the earlier-established element of transparency, a strong intermediary structure must find ways of linking involved actors and aim to establish long-term associations at the city level that bring prosperity, security and respect to Rio’s favelas. This emphasis on partnership-building aims to create checks and balances that prevent upgrading funds and actions from benefiting or becoming complicit with any illegal activity, such as those linked to militias or drug trafficking.

In order to adapt to the needs of each community, intermediary structures can take many shapes, just as favelas themselves greatly vary in political dynamics, location, size, processes of occupation and urbanization, topography, history, culture, and profiles of residents. Rio’s favelas cannot be treated as a single, indivisible entity. The intermediary structure for upgrading should be tailored to the identity of the place and of its community, increasing its potential for sustainability.

A further benefit of setting up an intermediary structure is that it facilitates the use of technical know-how that is based on each favela’s unique context. In addition, this knowledge gathering could be useful for favela exchange purposes, such as what occurs in Rio’s Sustainable Favela Network.* The intermediary structure facilitates processes like monitoring, evaluation, and recording lessons and good practices, while maintaining a human and community-centric approach. Ideally, it would also include an agent that can act as a filter of the interests, common grounds, and non-negotiable aspects of each stakeholder group, with a particular commitment to securing resident interests.

Moving upward along the pyramid, the next level consists of an integral multi-disciplinary approach. Historically, government-led urban development initiatives in Rio have occurred within the silos of individual sectors. Even the “best-practice” Favela-Bairro Program (1994-2010) lacked psycho-emotional and social components and produced limited results.

One of the biggest lessons to be extracted from Favela-Bairro is that physical and economic needs met by upgrading cannot be favored over social or emotional needs. It takes a balanced, integral, and multidisciplinary approach to address all anthropological needs of favelas, tackling their deficits while catalyzing their strengths. Addressing a variety of multidimensional shortfalls simultaneously allows for new synergies to emerge across a variety of dimensions (physical, social, economic, political, psychological, and emotional) and has a stronger chance of eroding the negative dynamics that ensnare many people in the informality trap.

As seen in the design of the subsequent Morar Carioca program (which was sadly never implemented), favelas must be upgraded individually, keeping in mind their relationships to each other and the city at large. Multidisciplinarity can help achieve this. Favela-tailoring and localized design should also take care to preserve urban scale and avoid isolation or “ghettoization.”

A multidisciplinary approach should help planners keep their eyes open to different realities and possibilities and avoid over-regulating the organic life that blossomed in the absence of public support. Favelas must not be substituted by “formal” structures, but rather complemented by them.

The ascend up our pyramid implies the gradual emergence of placemaking. According to architects Lynda H. Schneekloth y Robert G. Shibley, placemaking is “the way in which all of us as human beings transform the places in which we find ourselves into places in which we live.” These two levels of the pyramid further placemaking by advocating for the respect of every stakeholder’s interest and for the recognition of the multidimensionality of favela residents’ needs. Thus, upgrading works can reconcile the city and the favelas, operating alongside residents in realizing their aspirations on their own terms.

This is the fifth article in a six-part series.

Natalia Meléndez Fuentes is an MSc candidate in Building and Urban Design in Development at the Bartlett Development Planning Unit at University College London. Her research looks at urban informality learnings and the psycho-emotional elements of favelas and favela upgrading, mainly in Latin America.

*Catalytic Communities (CatComm) is the NGO that realizes both the Sustainable Favela Network and publishes RioOnWatch.