This is our latest article on Covid-19 as it impacts Rio de Janeiro’s favelas and is part of our ongoing coverage of the events of Black July.

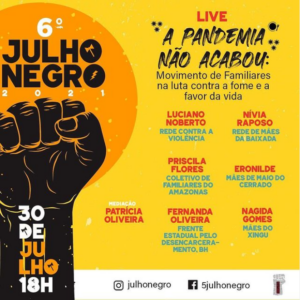

On July 30, the 6th edition of Black July—a widely-known Rio de Janeiro-based event within the global movement against racism and State violence—held the livestreamed event “The Pandemic Is Not Over: Family Movements in the Fight Against Hunger and for Life.” There, participating organizations shared their experiences and actions fighting hunger and offering other types of aid to favela residents in this delicate moment of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Moderator Patrícia de Oliveira, a member of the Network of Communities and Movements Against Violence, presented four speakers: Nívia Raposo of the Network of Mothers and Relatives of the Baixada’s Victims of State Violence, the Right to Memory and Racial Justice Initiative, and the Stop Killing Us Movement; Luciano Noberto, also known as Cuca, a member of the Network of Communities and Movements Against Violence; Fernanda Oliveira from the Minas Gerais State Front for Decarceration; and Priscila Flores from the Collective of Families and Friends of Amazonas’ Prisoners. The participants presented to an audience of 75 via YouTube.

Moderator Patrícia de Oliveira, a member of the Network of Communities and Movements Against Violence, presented four speakers: Nívia Raposo of the Network of Mothers and Relatives of the Baixada’s Victims of State Violence, the Right to Memory and Racial Justice Initiative, and the Stop Killing Us Movement; Luciano Noberto, also known as Cuca, a member of the Network of Communities and Movements Against Violence; Fernanda Oliveira from the Minas Gerais State Front for Decarceration; and Priscila Flores from the Collective of Families and Friends of Amazonas’ Prisoners. The participants presented to an audience of 75 via YouTube.

After initial introductions, Raposo launched the discussion by sharing how the pandemic has led to greater unemployment in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region. “This feeling of desperation took hold. It wasn’t just the virus. Hunger was also knocking at the door,” she said. She recalls it was difficult to get donations in the beginning, but that the Network of Communities and Movements Against Violence helped her, so she was able to start distributing baskets of basic foodstuffs to mothers. Over time, they also managed to get grocery card donations for the mothers. In Raposo’s opinion, the baskets don’t just contain food, “When you arrive carrying that basket, it’s not just about food, you’re taking dignity to that family. We also help with clothes, feminine hygiene products… We look at individual needs. We don’t help everyone, but we help most.”

Next, Fernanda Oliveira, who works for the State Front for Decarceration, in Minas Gerais, shared the challenge of having to choose whom to give aid to. “The more families we reach, the more families appear, and this forces us to establish criteria, which is very cruel and perverse. We keep establishing criteria of who is ‘hungrier,’ who is suffering the most from hunger among all those who come to us,” she said.

Along with baskets of foodstuffs, the demand for personal hygiene products for persons deprived of their freedom has also grown tremendously with the arrival of the pandemic. As Oliveira explains, “Historically, we always held drives for women, but the pandemic showed us the need to collect personal hygiene products for men as well, because their families, impoverished by the pandemic, could no longer afford to send them these kits.” During the pandemic, the organization has also been helping people experiencing homelessness with donations of hot meals, hygiene items, and clothes.

Prejudice is yet another obstacle in donation drives for organizations and movements that work to support persons deprived of their freedom and their families. As Priscila Flores, from the Collective of Families and Friends of Amazonas’ Prisoners, explained, “It’s very sad to see how these family members are treated. It’s as if the punishment spilled beyond prison walls. Our movement having been and continuing to be excluded from food drives shows that. When we launch a campaign, we get very little support.” The limited number of donations also forces the collective to select those who will receive what little help they can offer. For Flores, the pandemic has worsened and, above all, exposed the difficulties faced daily by the poorest. “The pandemic threw in everyone’s face a reality that we already knew existed, but that most insisted on turning a blind eye to. People are hungry and they need help. Unfortunately, we’re preaching to the choir.”

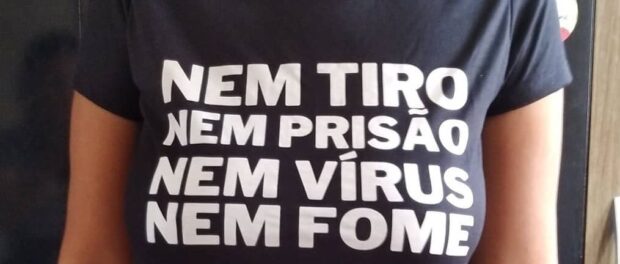

Next, it was Noberto’s turn to share what the Network of Communities and Movements Against Violence has been doing during the pandemic in Rio de Janeiro. The movement was one of the first to distribute baskets of basic foodstuffs but it faced difficulties beyond logistical challenges. “In City of God, we were delivering food baskets when the Military Police’s armored vehicle—the caveirão—came firing shots everywhere. Besides not helping with food, hygiene products, or medicine, they come in with the caveirão, putting our lives at risk,” he said. The episode mentioned by Noberto happened in May of last year. The shooting that interrupted the delivery of basic food supplies, leaving volunteers in the middle of the crossfire, ended with the death of João Victor, an 18-year-old black youth. Noberto also recalls that for the poorest portion of the population, it is not easy to stay at home during a pandemic, “It’s very difficult because we tell them: stay at home but, then, they open the refrigerator and there’s nothing to eat.”

Another topic of discussion was the importance of remembering the lives lost to Covid-19 and the government’s indifference to the increase in cases and deaths. “We all joined the stay-at-home campaign, whereas the government didn’t care. The governor had a party, got crowds of people together; the mayor [of Rio] had a samba circle… Many authorities got together and didn’t give the example they should have given. The economy is prioritized over life,” noted Flores, from the Network of Communities and Movements Against Violence.

After this first round, the speakers answered questions sent in by the audience, including how to help with donations. Their advice was to follow the movements through their social media, which are updated frequently and share all the information about campaigns taking place. “We can’t afford to be tied to the government, whether it’s the municipal or the state government, and even less to the federal administration. It has to be by us for us, one movement helping the other, one state helping the other, and that’s how we’ve been surviving,” said Noberto. The expression “by us for us” was the most used all evening to represent the lack of external support given to the organizations and movements that have been working to support families in vulnerable situations. The virtual meeting ended with the certainty that mutual support is the only solution for the moment, a sentiment shared in the speech by Flores, from the Collective of Families and Friends of Amazonas’ Prisoners:

“We have to unite, roll up our sleeves and help these people. They treat black and poor people as invisible. For them [authorities], it’s as if the favela resident didn’t exist. It’s a good thing that we have each other.” — Priscila Flores