For the original article by William Reis, Coordinator of AfroReggae, in Veja Rio, click here.

The Getúlio Vargas family estate, industrial development of Rio, route for Afro-Brazilians escaping slavery and Tia Dorinha’s resistance are all part of this history.

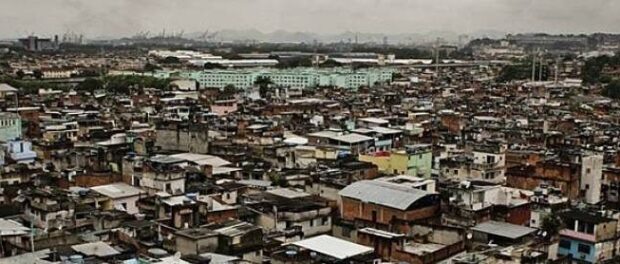

According to data from Rio de Janeiro’s city government, the Jacarezinho favela has an estimated 37,000 residents. Considered one of the most violent favelas in our city, it is also the blackest. Who will tell us the history of Jacarezinho is one of its local leaders, Rumba Gabriel, whose mother and father are, respectively, from the states of Espírito Santo and Minas Gerais. Gabriel has lived in the favela for 65 years.

The area where the Jacarezinho favela stands today belonged to the family of former Brazilian president Getúlio Vargas, who donated the space so that local families could settle. According to Gabriel, Jacarezinho was located in Engenho Novo and belonged to the group of districts that included Engenho Novo, Engenho de Dentro and Engenho da Rainha.

The Church of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception in Engenho Novo, transformed into a great shrine to Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception by Father Alexandre Língua, was built in this same spot. The skeletal remains of formerly enslaved people were found during digging for the shrine’s construction. Afro-Brazilians escaping the sugar mills located in Serra do Matheus, in Boca do Mato, used to hide in the region’s caves, then known as Preto Forro.

Gabriel mentions a samba song that tells this story: “There, to Serra do Matheus, in Boca do Mato, every freed black person headed that way, filled with the greatest joy.” The priest built the Souls’ Chapel in the spot where the skeletal remains were found. “Even today, if you go and visit, you’ll find these bones and you can learn this history. We can say Jacarezinho is a quilombo [lands occupied by the descendants of enslaved peoples whose enslaved forebearers are traceable to the same site], just like Morro da Matriz, Morro do Encontro, Morro da Cachoeirinha, Morro do Sampaio and Boca do Mato, since all of this land belonged to the Portuguese empire, which settled on what is now the Quinta da Boa Vista park. This whole region is where the Portuguese used to keep their horses, where the workshops were located. Jacarezinho comes from this history,” says Gabriel.

“It can be said that Jacarezinho is an urban quilombo. Lots of people think that quilombos are only found in the interior [of the country], but they forget the Afro-Brazilians brought to [work in] the towns. Rio de Janeiro received more than one million Africans to be sold into slavery at the Valongo Wharf, that has been abandoned, like everything else that belongs to us. [Many of] these people who arrived in Rio didn’t go to the interior. They went to places like [where today sits] Jacarezinho, where the largest concentration of Afro-Brazilians in favelas in Rio de Janeiro [ultimately] happened,” Gabriel continues.

In the geography of Jacarezinho as a favela, still according to Rumba Gabriel, the first settlements appeared around 1920. These people occupied the top of the hill, which was called Azul (Blue). He explains: “This characteristic of Afro-Brazilians building their homes on top of hills was exactly because of their fear of the police, who started playing the role of Capitães do Mato [men paid to recapture those who had escaped from the estates where they were enslaved], arresting people.”

In the 1930s, during the industrial period we call the Estado Novo, Gétulio Vargas created labor laws and many industries set up in the Jacaré neighborhood because of its central location and easy access to other neighborhoods like Tijuca and Ilha do Governador. “This is how Rio’s industrial park—Jacaré—was born, which was only second to São Cristóvão,” confirms Gabriel.

During that time, in which Rio was a major industrial center, Jacarezinho’s workforce was frequently used, encouraging local development. At that moment, when workers were benefitting from the labor laws of the period, residents of Jacarezinho had greater citizenship rights. Besides work opportunities, they also had access to better quality education, which contributed to Jacarezinho advancing more than other favelas in Rio. This leads us back to the discussion about the importance of social and economic development in favelas. Lack of investment leads to an increase in problems such a violence, unequal access to education, basic sanitation and many other social indicators that end up making Rio natives see only the negative aspects of the city’s favelas.

Rumba Gabriel tells another story, whose main character is also a priest. Carlos Nelson Delmonaco, better known as Father Nelson, built a chapel in a place called Cruzeiro. People said their prayers there, especially on Mondays, because it is the day of souls [Brazilian Catholics pray to souls in purgatory on Mondays]. This same priest organized voluntary collective activities and built Rio de Janeiro’s largest catholic church inside a favela, the Church of Our Lady of Perpetual Help.

Black culture has always had a close relationship with Jacarezinho. “The favela was always very black, until the arrival of white Northeasterners and the creation of that story of racial democracy, which doesn’t even exist in the favela, as argued by Gilberto Freyre when he created this whole fallacy,” says Gabriel.

The culture showed itself strongly through terreiros [places of worship for Afro-Brazilian religions]. There were between 10 and 15 Umbanda temples. These temples helped maintain Afro-Brazilian traditions in these urban quilombos and all were led by black women. “We had the temples of Tia Lurdes, of Tia Madalena, of Dona Ziza, and of Tia Dorinha. Tia Dorinha was 104 when she died in April of last year. She was our greatest source of resistance when the Neo-Pentecostal/charismatic churches came into Jacarezinho, converting residents and saying that our religions were a culture of evil, of hell and the devil. Tia Dorinha resisted all of this,” explains Gabriel, highlighting the constant attacks still endured by religions of African origin in Rio.

These attacks and lies increased the religious intolerance in Rio’s favelas. Scared, many people left the favelas. Others believed what they heard and ended up joining these religions. In one way or another, this contributed to our people losing a part of the legacy left by our ancestors. Today, there is only one Umbanda temple left in Jacarezinho and its drums beat quietly, perhaps in fear of further oppression. Tia Dorinha, when she turned 100, welcomed many different religious leaders to her celebrations. She was also invited to convert but turned down these invitations to the end of her days. Her house is still a temple.

Black culture is also preserved in samba: with the carnival bloco Não Tem Mosquito and with samba schools Unidos do Jacaré and União do Morro Azul, founded by Tia Andreza. Since she didn’t want a “divided city,” Tia Andreza organized the unification of these samba schools and created Grêmio Recreativo Escola de Samba Unidos do Jacarezinho, or Acadêmicos do Jacarezinho, that has been home to many samba musicians such as Gaspar, Cartola, Bezerra da Silva and Nelson Sargento. For this reason, samba school Mangueira was the godmother of Acadêmicos do Jacarezinho. The history of famous Monarco da Portela is also linked to the favela. “Monarco da Portela is from Jacarezinho. And why is he from Jacarezinho? At the time, he was a dealer for the jogo do bicho [an illegal gambling game in which different numbers are assigned to 25 animals]. A problem came up and one of his friends, who had a house in Jacarezinho, told him to go live there. This was at the end of the 1950s,” explains Rumba Gabriel, who was a friend of Monarco’s.

Rumba Gabriel is a leader from Jacarezinho, where he has lived for 65 years. He remembers some of the actions he carried out when he took over the residents’ association. His legacy includes building the Jacarezinho Cultural Center, whose objective is to look after the history of the favela; and the Jacarezinho Mixed Workers Cooperative, which has 18 workshops for carpentry, metalworks, upholstery, and clothes manufacturing, generating income to support over 100 families. When the digital era arrived and the people who worked in factories lost ground, Gabriel managed to get several computers and started IT courses to train residents. The courses qualified and certified 568 people. Gabriel also brought the Tupi orchestra into Jacarezinho. He recognizes the importance of other musical cultures in the favela and, for this reason, organized a performance in the Cruzeiro Square, which was attended by priests, commanders of the Military Police, police officers and chiefs, young people and residents.

When asked about former soccer player Romário, who was born in Jacarezinho but left at a very young age, Gabriel says that, after becoming a professional player, Romário came back a few times to play soccer at Abóbora Field, which is close to where he once lived. But, in Gabriel’s opinion, Romário could have helped the favela more. “Romário’s story here is interesting, but not very good. When he became famous, he should have left some kind of legacy. He should have shown his involvement in some way. He created the Romarinhos, which is kind of a small Olympic Village, but didn’t do anything here. Except when he was running for office.”

Like many activists from Rio’s favelas, Rumba Gabriel is threatened when he denounces police abuses. He filed official complaints with the help of state deputy Marcelo Freixo and city councilor Marielle Franco and had to leave the country. With the support of the Black Panthers, he left the favela and went to the United States. The Black Panthers were interested in the project created by Gabriel, Condomínio-Favela, which set up gates and cameras in favelas to monitor police activities. Faced with the warning “Smile, police officer, you’re on camera,” put up next to the cameras, police abuse decreased, but they tried to arrest and threaten Gabriel, who had leave to the United States.

This is the history of Jacarezinho, the favela with the largest Afro-Brazilian population in our city. Even with the oppression of black culture and police violence, Jacarezinho resists, the same as all of Rio’s favelas. Rumba Gabriel, who told us this story, is part of the legacy of resistance of a people who constantly need to reinvent themselves, so as to resist and guarantee that the stories of Gabriel and Tia Dorinha continue to be told to other generations. It was in Jacarezinho, Rocinha and Manguinhos that the last wave of tuberculosis claimed the largest number of victims, and little was said about it. These are places that have been abandoned by the State, where death and violence are seen as natural by a society which is only concerned when these social inequalities spill over and affect its privileges. Long live Jacarezinho!