The mansions that now line Niemeyer Avenue between Rio de Janeiro’s Leblon and São Conrado neighborhoods were built starting at the end of the 1950s. With the excuse that they were revitalizing the area, the company Melhoramentos do Brasil (Improvements of Brazil) removed the humble shacks that had been there, the homes of fishermen and descendants of slaves. The second wave of removals came in 1958. The third wave of removals, in 1977, was more violent and dangerous, with the participation of the military regime’s Secret Police. Displaced residents who didn’t want to move far away rebuilt their homes on the other side of the street, in what is now known as Vidigal. On his visit to Brazil in 1980, Pope John Paul II learned that this little favela in Rio de Janeiro’s South Zone had recently adopted a word that was very important in those days: resistance. Delighted by the passion residents had for the place, his Holiness the Pope presented the community with his ring. Newspapers at the time reported, “Vidigal is one of the symbols of resistance; it’s the Pope’s favela.”

Residents tell how they have fought removals since the 1960s.

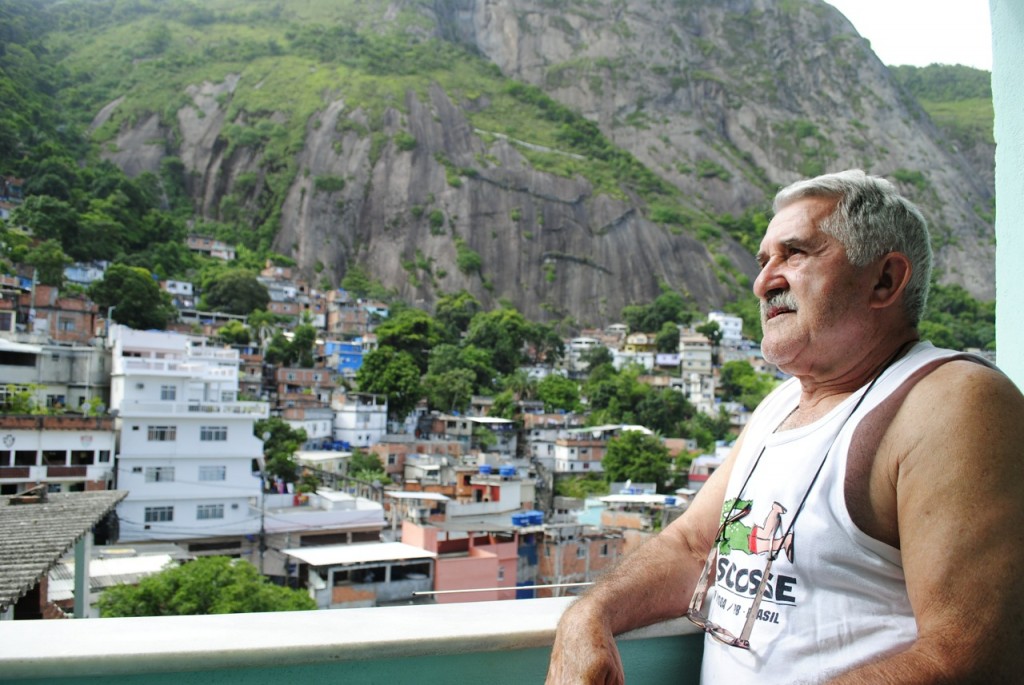

“We residents have always been well-organized. We offer our enthusiasm for protecting our land as a gift to future generations. Only the person who builds his own house knows how much love went into it. Today it’s easier. People buy their houses already built and don’t have any ties to them. If you go out and ask anybody on the street about the history of Vidigal, nobody can tell you what really happened. It’s sad. If we’re known for our beautiful view and our artists, it’s thanks to the warriors of the past. My fear is that this generation of new residents will let our history die,” says 71-year old Armando de Almeida Lima, one of the founders of the Vidigal Residents’ Association, established in 1967.

With pacification, more people are moving to the favela.

São Paulo native E.B., 36, is yet another person who has decided to call the favela his home. He used to come to the city to visit his father, and every time he went to Arpoador he couldn’t help but notice Vidigal. He had the option to get an apartment in Ipanema, but chose instead to live in the favela.

“At the time I knew about the pacification and I thought it would be a great opportunity because of the location and the good price. By chance, the owner of the space is a man I had already met,” says E.B., who used to coordinate market development, including in Mozambique, and today works in nutrition.

Portrait of the Future?

The breathtaking view from the Arvrão lookout point; the huge line for the motorcycle taxi at the bottom of the hill; packed bars and churches; Luís’s hot dog stand, more and more popular all the time. So different from the 1960s, when there was no sewerage system or running water. Pacification has accelerated a process that had already begun. Real estate transactions are now looked on favorably, and today’s buyer knows what he wants to buy, and where to buy it. We know there is still a risk of removals. We only have to look at the case of Carlos Duque Street at the top of the hill to have an idea of how serious the problem is. Older residents protest, making it clear how shocked they are by the presence of these new neighbors. Meanwhile the new residents try everything to win over the old-timers, and so the game of cat and mouse goes on. Some people move away, many move in. It’s common now to see “For sale/A venda” signs scattered throughout the favela.

And Vidigal, the 54-year old gentleman, watches from his box seat and remembers when we were all just a bunch of fisherman.