This article is part of a series on energy justice and efficiency in Rio’s favelas. It is also part of a series created in partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University, to produce articles for the Digital Brazil Project on human rights and socio-environmental justice in the favelas for RioOnWatch.

“People say solar energy is only for the rich. That’s a lie, and we prove it right here. Small businesses, institutions, and cooperatives located in the favelas of Babilônia and Chapéu-Mangueira have shown the world that solar energy is possible in poor areas,” states Valdinei Medina. Born and raised in Chapéu-Mangueira, he currently lives in its neighboring community, Babilônia, both situated in Leme, a beachfront area in Rio de Janeiro’s South Zone. Dinei, as he is known, is one of the local leaders that form RevoluSolar, a non-profit association dedicated to solar energy installations, vocational training courses and environmental education in the two favelas.

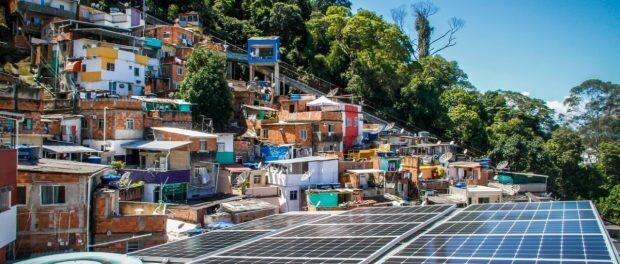

The first installations were set up at two local ventures, the Babilônia Rio Hostel and the Estrelas da Babilônia Guesthouse. Five years after the pilot projects’ completion, residents are getting ready for the launch of Brazil’s first solar energy cooperative in a favela. The electricity generated by the panels, located on the roof of the Residents Association, will benefit approximately 35 families from Babilônia and Chapéu-Mangueira.

The solar panels’ assemblage was completed in February of this year, and the cooperative is now starting to operate. The beneficiary households will obtain a reduction of about 30% in their electric bills and will consume clean energy. “We held several meetings with the residents’ association, we asked who wanted to participate and let them know they needed to be properly registered with the electric utility. Initially, approximately 120 people signed up and, from this group, we drew up our plans. Today, we may say solar energy has generated great local interest, in part due to the fact that the local power utility, Light, charges by estimating electricity consumption here in the favela. Besides being expensive, the existing service is very bad,” Dinei explains.

Part of the amount saved on electric bills will be transferred, on a monthly basis, to the cooperative, to compensate the local workers involved in the installation. According to Dinei, the expectation is that this model will allow for the project scope to be expanded in the community and, in the future, to be duplicated in other favelas and even at public institutions. “We believe the solution for the city, for the country, will come from poor and peripheral areas,” Dinei expressed.

Across from the residents’ association, where the solar energy cooperative will operate, is the Tia Percília School, a community organization created three decades ago. The name is a tribute to its founder, a local leader involved and concerned with expanding access to education and culture among the children and youth of Babilônia and Chapéu-Mangueira. Nowadays, one of Dona Percília da Silva’s sons is the school’s caretaker. His name is Carlos Antônio Pereira, better known as Palô. The school was the first community institution in Babilônia to receive solar panels in December 2018.

The Tia Percília School serves children from both Babilônia and Chapéu-Mangueira communities completely free of charge. It maintains its activities through donations. The electric bill was one of the main costs and weighed heavily on the institution’s tight budget. “We have seven or eight rooms, our energy consumption is high because we need to run fans, air conditioning, refrigerators, freezers, and computers. Electricity charges were a main concern, since whether you’re open to the public or not, the bill shows up and someone has to pay,” states Palô.

Before the photovoltaic system installation—technology that converts the sun’s energy into electricity—energy bills ranged from R$700 (US$129) to R$1,000 (US$184) per month. “The costs were awfully high. They significantly impacted our budget and, often, our contributing partners did not understand how a favela was generating such a high bill. How can I ask for a donation and tell someone that I spend R$1,000 a month on electricity? Those charges are heavy, they can’t be explained; it’s difficult to get people to understand,” Palô explains.

Once the system started running, electricity charges were reduced 85% on average, fluctuating between R$100 (US$18) and R$150 (US$27) per month. Savings have exceeded expectations, according to Palô. Additionally, during the months when the system generates more energy than the school consumes, electricity is sent back to Light’s grid and turned into credits. These can then be used to offset higher charges later on.

The budget is not the only item impacted by solar energy installation. The solar panels’ presence in community spaces, such as the school and the Residents Association, has brought clean energy closer to residents’ daily lives. “We might hear about solar energy on daily newscasts, but once you see it in actual practice, you realize it is possible,” notes Palô. Although “blue roofs” can increasingly be seen from hilltops, he says solar panels still stir curiosity in children and adults alike.

As Dinei explains, bringing about environmental education in the community is a significant goal for the project: “It is still a distant target, we have lots of debates and challenges ahead of us. We are starting a film club, publishing a primer; then there’s the group that works with early childhood education, and some folks working relentlessly to address the topic of clean energy, transforming solar energy into a more popular concept, translating it into a subject that is easier for residents to understand.” Tia Percília School has various activities centered on the environment. Children there are learning from an early age what solar energy is and seeing, from a practical point of view, how it works to convert the sun’s energy into electricity.

Similar work takes place at the Children’s World Community Daycare Center, a solar energy pilot project sponsored by another non-profit organization’s: Insolar. The community daycare, founded 38 years ago by women from the Santa Marta favela, also in Rio’s South Zone, implemented the solar system in 2016. The daycare was the project’s pilot, and in the last five years Insolar has installed over 200 solar panels in Santa Marta, the majority in common spaces used by residents, such as daycare centers, the Family Health Clinic, the Residents’ Association, as well as stations of the local funicular tram system.

Director of the Children’s World Community Daycare for 27 years, Adriana da Silva recalls that, when she initially received the solar plates installation proposal, she did not know much about solar energy. The expectation was to reduce electricity and allow for these savings to be used in improvements for the children’s physical spaces and nutrition. After implementation, electricity charges were significantly reduced, as promised. However, impacts noticed by Silva go beyond financial benefits. “This is a very valuable lesson because we learn so much, things that until then we only saw on television. When we see things up close, we see how they work, and then we can really tell how the electricity charges went down,” she says.

As the daycare center was the first place to have solar panels in Santa Marta, Silva recalls many people asking about the system. Over time, other institutions were included in the project and roof plates became a regular sighting in Santa Marta. Additionally, environmental education workshops and vocational courses helped popularize clean energy. “Within the community, lots of people were very curious. Nowadays they don’t ask as many questions as before. Coming up on the tram, you can see the solar panels in various spots. It was a novelty in the beginning, today it’s a more familiar sight,” notes Silva.

Spreading solar energy information is part of Verônica Moura’s mission. Moura was born and raised in Santa Marta and is Insolar’s ambassador. The first research done on site, during the project’s implementation phase, was carried out by community residents, trained in a course coordinated by Moura. Today, when she visits organizations that have photovoltaic systems, she feels great pride in the fact that the favela where she was born was one of the pioneers in solar energy.

The new scenario produced in recent years is part of everyday life for Santa Marta’s newer generations, who realize from a young age that the favela is a place of potential. “To see our children learning about it, seeing solar energy on the roofs of their institutions… They ask questions, they want to know, and this exchange is very important. From a young age they already know that, yes, we can have this technology in our community,” argues Moura, herself mother to a 12-year-old boy and an 8-month-old baby girl.

The solar energy system set up at the Children’s World Community Daycare, as well as at the Tia Percília School, in Babilônia, was possible due to the involvement of several partners who supported these projects with resources and technical knowledge. Insolar and RevoluSolar act as conduits, democratizing and facilitating solar energy access in the favelas. These organizations also give professional training to local residents, who in turn are able to implement new systems and maintain those already running in the community.

Employability and Income: Opportunities Flowing from Clean Energy

Leonardo Luis discovered solar energy between 2015 and 2016. At that time, he was unemployed and earned a living selling cleaning products at one of the entrances to Santa Marta. He recalls his greatest concern was to ensure his daughter’s livelihood. One day, he was invited by the co-founder of Insolar, Henrique Drumond, to participate in a training course to learn about electrical circuits and photovoltaic systems, as well as specific solar industry safety standards.

In the last module of the course, when Luis was starting to learn about solar power systems, the first projects were being set up at Santa Marta. Since the course completion in 2017, solar energy changed not only the scenery in the community, but Luis’ life as well. He is now an entrepreneur, leading a four-person team. All are Santa Marta residents and former Insolar professional training participants. “Today, I have made a name for myself in this market, one company recommends me to another,” says Luis, whose first jobs were on the community’s panels.

Professional qualification changed not only Luis’ life, but the lives of his inner circle of family and friends. “Solar energy changed everything in my life. I can also create opportunities by teaching other friends about solar energy and even take them, when possible, to work with me,” explains the entrepreneur. “I, who had never had a profession, was able to, all of a sudden, connect with this type of technology… it had an enormous impact on my and my family’s life. Today, all my brothers say they want to learn as well,” he says.

New Solutions, Old Problems: Solar Energy Challenges in the Favelas

The main mission of the Estrelas da Babilônia Hostel, a solar energy pilot project in the Babilônia favela, is to be a sustainable establishment. In addition to the 2016 solar panel installation, the building has a green roof and runs recycling and composting. One idea present from the very beginning was to reduce the impact of its operations on nature. Leading this small venture is a Colombian, Bibiana Gonçalves, who has been a resident of Babilônia for eight years.

“Solar energy for our little venture was an amazing thing, because it seemed like everything we were toiling for, the little profit we could generate from a favela business, went into paying for electricity,” Gonçalves says. In the first month of the solar panels’ operation, previous charges that ranged from R$950 (US$176) to R$1,300 (US$240) fell to about R$300 (US$55) per month. In a short time, electricity savings were used to pay off the loan taken out to buy the solar panels.

“The biggest challenge is the electric utility, Light,” explains Gonçalves, who complains about the difference between the service provided for customers located in the formal city versus those in the favela. Problems with Light began right at installation, when the hostel’s solar system was first connected to Light’s grid. “You have no idea how many calls I had to make to get the electric company to come and do its part,” she recalls.

According to Gonçalves, for the past two years, problems with Light not only became more frequent but have gotten worse. The power box to which the hostel’s solar system is connected started to malfunction. The electric company made several repairs until, in November of last year, the transformer stopped working altogether, leaving the hostel and all the residences on its street without power. If the solar panels cannot be connected to Light’s grid, there is no power. “All the temporary solutions found by the workers have stopped working. So, now, all the energy in my house is connected directly to the main supply, bypassing the meter. I am unable to measure my electricity consumption, I haven’t been generating solar energy, and all this amazing sunlight that’s been shining on the panels has been lost, and not even Light is benefitting from this energy,” Gonçalves explains. Light has included Gonçalves’ name on a bad payers list after she was unable to keep up with her electric bills which, without the solar panels, went back to exceed R$1,000 per month.

According to Eduardo Avila, executive director of RevoluSolar, the most commonly found solar energy systems in Brazil are those connected to the local power company’s grid, running in an integrated manner. When solar panels are installed, part of the grid’s equipment is replaced, such as the meter. In a conventional grid, meters run one way and measure only the energy consumed. In photovoltaic systems connected to the power company’s grid, on the other hand, the regular meter is replaced by a two-way indicator, which measures not only consumption, but also the electricity produced by the home itself. When the system generates excess energy, this electricity is injected into the main electric grid and individuals get credits which can later offset their regular bills.

Involved in several environmental projects, Gonçalves says she believes in solar energy’s potential, though she claims it is imperative that authorities and businesses change their attitude toward favelas. In her view: what is the point of investing, of dreaming, of working with technology, when public and private institutions, needed as partners for these projects to succeed, continue to underestimate favelas, continue to consider favelas as something inferior?

Asked to comment on the implementation of solar energy projects in favelas, as well as on the service issues encountered at the Ladeira Ari Barroso Mirante, where the Estrelas da Babilônia Hostel is located, Rio’s electric utility, Light, did not respond.

About the author: Jaqueline Suarez is a journalist and master’s student at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), in Niterói. She is also a community journalist and independent documentary filmmaker. She lives in the favela of Fallet, in Santa Teresa, Central Rio.

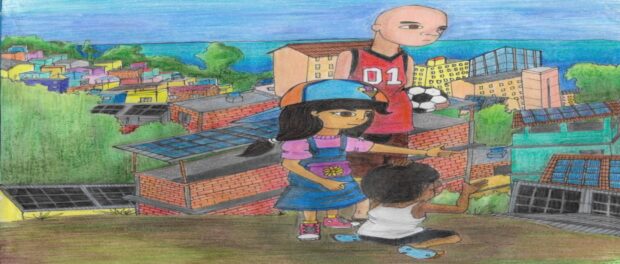

About the artist: A student of visual arts, an artist and a graffiti artist, Gilberto FAO is also a cultural organizer and an independent events producer. He lives in the neighborhood of Chácara Santana, in Capão Redondo, in the South Zone of São Paulo.

This article is part of a series on energy justice and efficiency in Rio’s favelas.