This article is part of a series on energy justice and efficiency in Rio’s favelas. It is also the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

In the beginning of the 20th century, when Rio de Janeiro was still Brazil’s capital and in the throes of the urban reforms promoted by Pereira Passos—a mayor driven to transform the national capital into a modern city—electric lighting was adopted for streets and households. This first power grid was designed to supply only the Port Region and surrounding areas, where the aristocracy lived. In bringing electric lightning to the city’s downtown region, Centro, the hygienist policy removed black and poor people from the region, relegating them to the capital’s margins.

Many stories regarding Rio’s urbanization and Pereira Passos’ reforms have been erased. It is important, however, to understand the productive forces that allowed Rio’s downtown to undergo such a rapid and major transformation. Investigating the workforce, materials and logistical strategies deployed might shed light on the period and scars left behind.

Some questions are particularly relevant in this historical reflection. What was the primary energy source involved in this early 20th century transformation of Rio? Who were the producers and suppliers of this energy? From where was it extracted? How does the history of this process relate to the city’s current energy injustices?

Charcoal Workers: A Link Between the Forest and the City

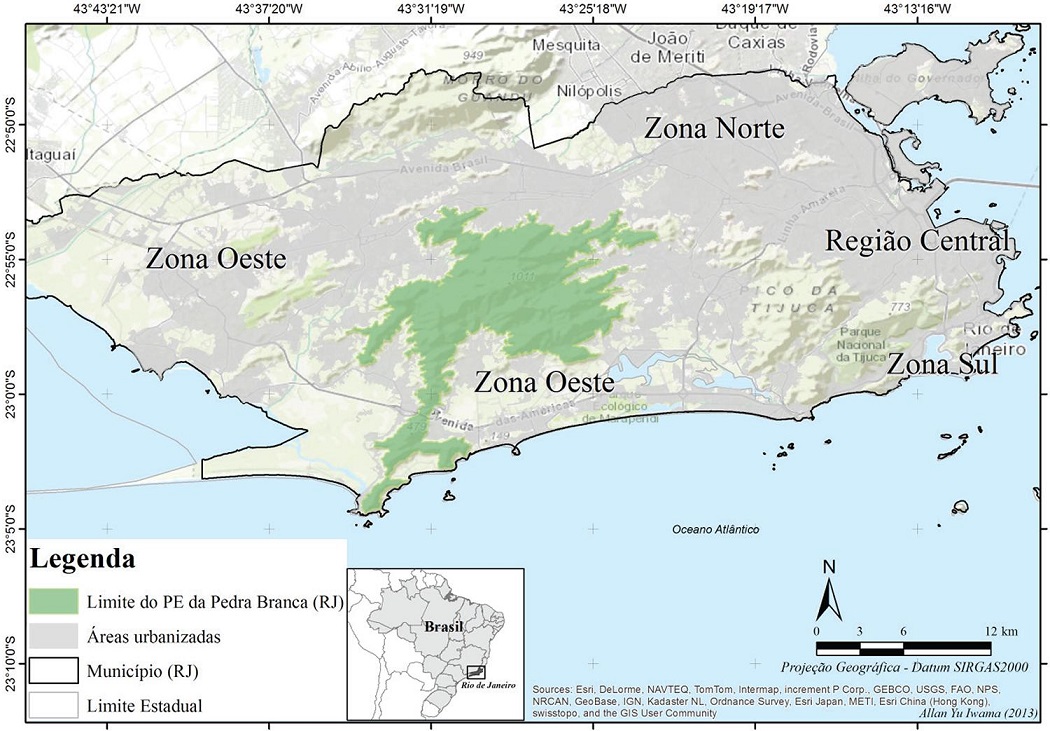

Located in what is today Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone, a compact group of mountains called the Pedra Branca Massif is part of one of the largest urban nature reserves in the world: the Pedra Branca State Park. To this day, the park contains three quilombos, as ancestral lands occupied by descendants of enslaved people in Brazil are called. These are: Camorim, in a neighborhood by the same name; Cafundá Astrogilda, in Vargem Grande; and Dona Bilina, in Campo Grande. In the past, this region was a great mill, and its forests provided the wood needed to generate energy for the production of sugar, coffee and charcoal during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

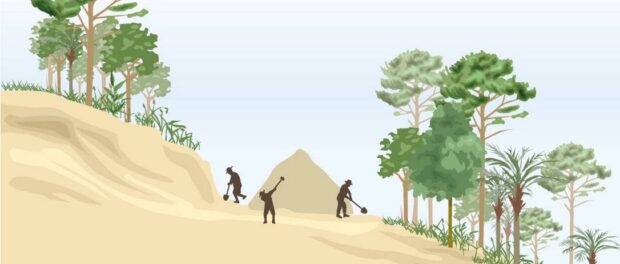

After the abolition of slavery in Brazil in 1888, the forest continued to be used as a source of charcoal. Fragments of small kilns that used the charcoal pile technique have been found in several parts of the Pedra Branca Massif. Over 1000 kilns have been mapped. The charcoal workers were likely individuals initially enslaved in the region’s mills, who saw charcoal production as a source of subsistence after abolition. These people lived inside and from the forest. In the areas where charcoal kilns have been found, the cultivation of ritualistic, edible, and medicinal plants can be found, as well as stone ruins—possibly shelters used by charcoal workers.

During the city’s urbanization, charcoal was the main energy source, essential for several activities in civil construction. One of its most intensive uses was for forging and sharpening the tools that cut stones for paving streets and for creating the structural elements of the imposing buildings we still see in downtown Rio.

We can therefore say that the Pedra Branca Massif was responsible for fueling the furnaces and forges that transformed Centro’s landscape following Pereira Passos’ reforms, transferring massive quantities of energy from the forest to the city. Far from Rio’s aristocracy’s eyes—dazzled by electric lights—recently freed Afro-Brazilians cleared the forest and transferred its energy to Rio’s center with their charcoal-making technology. The charcoal brought from the distant West Zone by these invisible workers turned into reality the dream of a metropolis built for a few. Therefore, while gazing Rio’s urban spaces, we are also looking at the forest and at the exhausting work of charcoal production, carried out by black Brazilians forgotten by the State.

The Massif’s Inhabitants in the 21st Century

Today, this same region is home to traditional farmers—some of them direct descendants of the early 20th century charcoal workers—all of them heirs to the forest peoples’ traditions. While subsisting from the land, they guarantee healthy food for the city. You can meet them at agroecological open-air markets throughout the city. The forest’s well-being depends on the survival of these farmers. Contrary to the prevailing thought that opposes human presence in conservation units, these women and men are true guardians of the forest.

The clandestine nature of the quilombos, the long expansion of the city’s urban limits toward the West Zone, and the criminalization of agriculture in the Massif once the conservation unit was established have kept these farmers disconnected from the city at large as they continue living throughout the Massif. Despite officials’ attempts to erase Rio’s rural vocation and the isolation of life in the Massif, inhabitants remain in their territories because they relate to the land with a sense of belonging.

In maintaining their heritage, the Massif farmers ended up sacrificing their access to health and education services and were cut off from electricity and telecommunications services, in some cases to this day. Although their ancestral lifestyle is adapted to the absence of electricity, they are denied many rights because of this exclusion. This is a sacrifice that should not exist: essential services should also be granted to them while respecting their way of life and their territory. They are residents of the municipality of Rio de Janeiro, after all.

This is precisely the contradiction that guides this article: over a century later, the descendants of the workers that produced the energy source used in the urbanization of Rio’s downtown are being denied access to electricity.

Farmer Francisco Caldeira lives in a remote ranch in Vargem Grande. He tells us how hard it is to live without electricity: “I wish I could have light at night, a fridge to keep food, and an outlet to charge my phone. I could use a TV too, especially in the evenings.”

Caldeira knows how important the voice of Rio’s farmers is for the city. He is a well-known presence in agroecological debates and, in spite of his geographical isolation, presided over the city’s Food Safety and Nutrition Council in 2014 and 2015.

Massif farmers recognize the importance of their presence in the forest but they also know that, isolated as they are from the rest of the city, they lose their voice. Access to electricity makes the integration of Massif residents with the rest of society easier. It guarantees their health and well-being, besides consolidating their political rights.

Massif farmers recognize the importance of their presence in the forest but they also know that, isolated as they are from the rest of the city, they lose their voice. Access to electricity makes the integration of Massif residents with the rest of society easier. It guarantees their health and well-being, besides consolidating their political rights.

Some might argue that if electricity is so important to the residents of the Massif, they could simply move to a place where it is available. Those who make these claims do not recognize Massif residents’ existence as farmers or as inhabitants of that territory. This lack of recognition relays their desire for a homogenized, non-rural city: the desire to silence the rural vocation of the city of Rio in favor of the image of a modern and eminently urban metropolis. Some, imbued with this colonial urbanizing logic, may pity these farmers’ next generations and question, “Why don’t they come to the city? Why remain bound by so many limitations?” Yet, we must also recognize the importance of these farmers in the city. Granting them the right to live in the forest without demanding they give up the technological advances available to the rest of civilization is to guarantee quality food for Rio’s population, the continuity of an ancestral knowledge of care, and the conservation of the Pedra Branca Massif.

Paths Towards Energy Justice in the Territory

In 2002, Law 10,438 established electricity as a universal public service, granting everyone the right to electricity. The Brazilian National Electric Energy Agency (ANEEL) recognized universal access within the local utility, Light’s, concession area in Rio in 2004, in compliance with a 2007 administrative order (991). In other words, as far as Light is concerned, the entire population of Rio has access to electricity.

The story of Caldeira and other farmers shows this is not the case. Although universalization has been formally recognized, the city of Rio presents territorial complexities that require added investigative and political efforts from the utility, the authorities and society at large with the aim of truly guaranteeing this right.

A technology with great potential for the electrification of remote areas is solar energy. Its use has become increasingly popular in Brazil: from large, centralized plants to small home generators. One of the most consolidated ways of using photovoltaic systems involves taking batteries to places not served by an energy grid. In the Pantanal of southern Mato Grosso state in Brazil and in the Amazon, for instance, the local power utility uses photovoltaic generators in conjunction with batteries to make the universalization of access possible even in remote communities.

In order to make the access to electricity truly universal in Rio de Janeiro, we need to face the challenge of taking it to the farmers of the Pedra Branca Massif. From a technical standpoint, this is not a simple task because it deviates from what is standard. It will be up to the utility to evaluate the best way to grant this right, considering the most adequate solutions for a conservation unit and its restrictions, taking socio-environmental impacts and cost into account.

About the authors:

Iamni Torres Jager is a popular educator and biologist with a Master’s in Science, Technology and Education and is currently pursuing a PhD. A resident of the Quilombo do Camorim, she is a participant of the Baixada de Jacarepaguá grassroots movements and activist in the fight for housing, food safety, and popular economy from an agroecological perspective. She is a member of the West Zone’s Web of Solidarity, the Popular Collective of West Zone Women, and the Vargens Popular Plan, among other groups.

Antonio Alonso is a civil servant, resident of Quilombo do Camorim and student of Public Administration. He currently works with the installation of photovoltaic systems in Rio de Janeiro.

About the artist: Natalia de Souza Flores, born and raised in Rio’s North Zone, is a member of Brabas Crew. With a degree in Graphic Design from Unigranrio in 2017, she has worked as a designer since 2015. She launched a magazine of collective comics called ‘Tá no Gibi’ in 2017 at the Rio Book Biennial. Her main themes are based in African culture, using cyberpunk, wicca and indigenous elements.

This article is part of a series on energy justice and efficiency in Rio’s favelas. It is also the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.