This is the first of three articles that cover the roundtable discussions of the Color of Mobility project. It is also the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

“Why does urban mobility need to be anti-racist?” This question was the subject of a roundtable held on October 13 by the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP), in partnership with the São Paulo Association of Urban Cyclists (Ciclocidade) and Pedal in the Hood. Participants reflected on the difficulties and inequalities that permeate the experience of Afro-Brazilians with urban mobility.

This was the first in a series of three meetings that make up the actions of the Color of Mobility project, which aims to bring awareness to the effects of racism on how the black population transits through cities. This first roundtable included Rafaela Albergaria and Paíque Santarém, authors of the book Anti-Racist Mobility, and ITDP communications coordinator, Mariana Brito, who moderated the conversation.

Neste mês de outubro o ITDP Brasil e a @ciclocidade irão promover três encontros para discutir e refletir sobre como o racismo estrutural afeta o acesso, a oferta e a prestação dos serviços de transporte público no Brasil.

Inscreva-se: https://t.co/hZRzDOwmtL pic.twitter.com/XAcCk81Vjl— ITDP BRASIL (@ITDPBRASIL) October 5, 2021

This October, ITDP Brazil and @ciclocidade will promote three meet-ups to discuss and reflect on how structural racism affects the access, supply and rendering of public transport services offered in Brazil.

With a master’s in Social Work, Albergaria is a researcher in the areas of Human Rights, Public Policy, Urban Mobility, and Institutional Racism. In 2019 she published It Wasn’t In Vain: Mobility, Inequality, and Safety on Rio’s Metropolitan Trains, co-authored with João Pedro Martins and Vitor Mihessen. The work is the result of extensive research on train-pedestrian fatalities on SuperVia trains, which serve Greater Rio de Janeiro. One of the stories told is that of Joana Bonifácio. Bonifácio was Albergaria’s cousin, who died at the age of 19 trying to board a train at the Coelho da Rocha Station, in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region, in the municipality of São João de Meriti. Her cousin’s death made the close relationship between race and the precariousness of rail transport and, more broadly, the influence of racism on urban mobility, jump out to the researcher.

A member of the Free Fare Movement and of the Black Movement, anthropologist Paique Duques Santarém is a doctoral candidate in Architecture and Urbanism at the University of Brasília (UNB). The relationship between racism and the structuring of urban mobility in the country is at the center of his analysis as a researcher. As Santarém argued during the event, racist mobility “is a concept born from life experience, a real lived experience.”

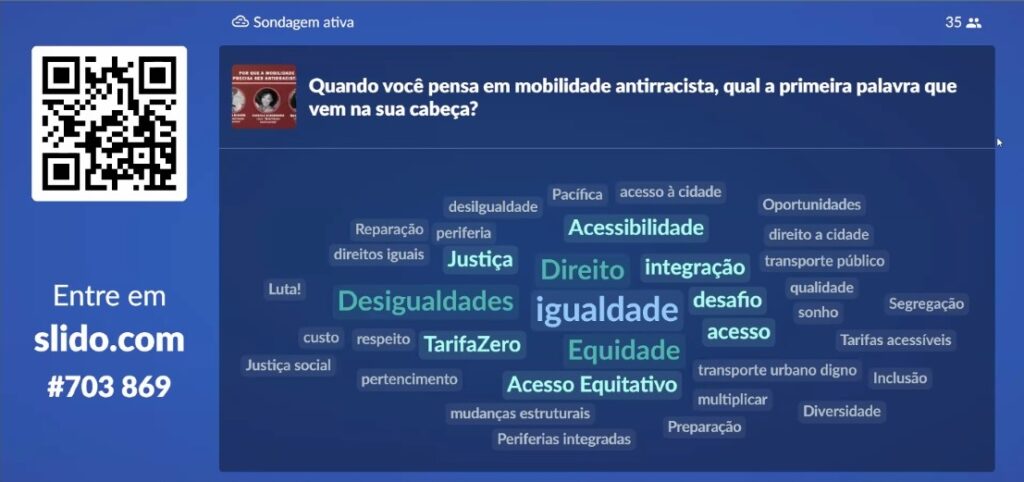

The meeting began with an invitation for those present to participate: “When you think about anti-racist mobility, what is the first word that comes to mind?” From this provocation, those present indicated terms that relate to the topic. Equality, equity, law, and inequality were the words most used.

Borrowing a few verses from the poem “Passenger from the last railcar,” by Elisa Lucinda, which opens the book Anti-Racist Mobility, Mariana Brito hinted at what would be discussed:

“I’ve spent my whole life scared of missing the train.

I’ve always lived far from dreams, far from money, from school, from art, from rest.

I calculated my life so I wouldn’t miss the train.

I did the math:

distance plus city broken in the middle

equals the path walked in vain.

[…]

And now, at the end of the night, it shows up exactly on time, as do I every day because all I’ve done in life is so as not to miss the train now.

chaos, screams, for help,

people yelling “stop”

someone else asking who?

half my body, pulled apart, and collected from the gap.

And, I, who struggled all my life not to miss the train.

I lost my life on the train.”

The relationship between racism and urban mobility can be seen from different perspectives. At the base of this problem is the strangeness of racism within institutions, its influence on the organization of spaces, in the hierarchy and differentiation of people, and in the establishment of public policies. Quoting Frantz Fanon, Santarém explains that “racism is a system of differentiating people, which only exists when it manages to build hierarchies in all of society and these hierarchies can interfere in all institutions.”

He goes one step further in his argument, “In order to reproduce itself, this structure acts in all institutions, in every existing space in society; it is something secular, something that replicates and changes form. The main characteristic of racism, for me, is its capacity for transformation, its ability to adapt to different social systems, and to maintain itself as a structuring force… So, if racism gives structure to all institutions, and if mobility is one of our society’s institutions, it stands to reason that racism will organize it, right?” questions Paique Santarém.

According to the researcher’s assessment, urban mobility cannot be seen as a consequence of socio-spatial segregation. On the contrary, it should be understood as an active, building agent of a policy that distances the black and low-income population from affluent areas. Far from the centers, this population is also, therefore, far from infrastructure and public services. This gap grows increasingly as cities—their services, opportunities, and infrastructure, including modes of transport—continue to develop unevenly, concentrating investments and opportunities in certain areas and making others precarious.

According to the researcher’s assessment, urban mobility cannot be seen as a consequence of socio-spatial segregation. On the contrary, it should be understood as an active, building agent of a policy that distances the black and low-income population from affluent areas. Far from the centers, this population is also, therefore, far from infrastructure and public services. This gap grows increasingly as cities—their services, opportunities, and infrastructure, including modes of transport—continue to develop unevenly, concentrating investments and opportunities in certain areas and making others precarious.

This mismatch that affects the existence and survival of black bodies so intensely comes from long ago. “The slave ship was the first space of racist mobility, which underwent an enormous push while cities were being born and structured and trams and trains were being set up… Until the 1930s, trams and trains were, simultaneously, mechanisms used to integrate cities and to segregate the black population, both because they could move this population further away and because of the rates imposed,” illustrates Santarém.

At the time that cities were being set up, hygienist and eugenic ideals populated the imagination and experiences of those responsible for creating public policies and organizing urban spaces. In Santarém’s view, racist mobility continues at work in building tools for segregation, which can show itself in various forms. He gives various examples: “The way I look or the attacks I will suffer in the streets; my territory being more precarious; my getting on the bus, having less income and not having access to bus vouchers; or, my being on the bus and bouncing all over the place; or, being on the bus and people not sitting next to me; the bus not stopping for me; or, the train not going where I need it to go, or when it does, having terrible infrastructure, one that is much more susceptible to accidents… That’s it. All aspects of mobility have a link with racism,” Paique Santarém concludes.

“The metrics that determine transport calculations are based on the dehumanization of our bodies,” reflected Rafaela Albergaria at the beginning of her address. The researcher recalled the death of her cousin, Joana Bonifácio, who was dragged and killed after having her leg stuck in the train door as she tried to board it. According to Albergaria, her view of urban mobility comes from a struggle for reparations: “It has to do with remembrance, with thinking about the fight for justice and the guarantee of non-repetition. I always talk about Joana because remembering, and exercising the memory of those who came before us, and who were important to us, is also a political production of existence and life.” Based on the understanding that a social problem is only targeted by public policies once mapped, Rafaela started to collect data and talk to people who use the trains, thus initiating the research that would result in the book It Wasn’t In Vain: Mobility, Inequality, and Safety on Rio’s Metropolitan Trains.

In the researcher’s understanding, racism operates through a policy of interdiction as opposed to a policy of access, having a eugenic perspective of organizing the public space as its starting point. She argues that, “White bodies access institutions from a place of guaranteed (rights). Black bodies access institutions and public spaces from a place of interdiction… Which bodies will access cities and rights? What are the bodies that will access the city from a standpoint of interdiction, control, and extermination?”

According to Albergaria, the eugenic theories and policies that fostered the construction of cities show their effects on the conditions of the access of black and low-income populations to cities, opportunities, and rights.

Albergaria believes that this access, permeated by deep inequalities, is heightened by the absence of reparations policies in the post-slavery period. Also according to her, what were actually observed were numerous policies created to maintain or even accentuate the precarious conditions of life and survival of black people. This logic of differentiating and establishing hierarchies manifests itself in all spheres of life, including transit. Albergaria draws attention to the impacts of this on people’s daily lives. “If you want to access any social policy, you need to get around the city. If you want to go to the health center, which is close to your house, you need to get around. The mobility policy is decisive for our existence.”

Albergaria believes that this access, permeated by deep inequalities, is heightened by the absence of reparations policies in the post-slavery period. Also according to her, what were actually observed were numerous policies created to maintain or even accentuate the precarious conditions of life and survival of black people. This logic of differentiating and establishing hierarchies manifests itself in all spheres of life, including transit. Albergaria draws attention to the impacts of this on people’s daily lives. “If you want to access any social policy, you need to get around the city. If you want to go to the health center, which is close to your house, you need to get around. The mobility policy is decisive for our existence.”

If survival is directly influenced by one’s ability to transit through the city, then we must fight to rework the policies and logic from which mobility operates. About this, Paique Santarém alludes to the transformations that have taken place in universities in recent years: “The Brazilian public university is a racist institution… but, today, it has effective affirmative action policies. Is that enough? No, but it’s creating spaces for Afro-Brazilians to fight for more within universities, knowing that the university will only be anti-racist when it is refounded. But it does have anti-racist policies within its walls. So, we can institute anti-racist policies in transport, knowing that mobility is a racist institution. I think that’s the direction we have to work in.”

Regarding this subject, Albergaria also defends the construction of affirmative action for transit, based on concrete experiences. According to the researcher, the gap existing between mobility policies and the needs of the black population, is supported, on the one hand, by intentional projects of interdiction and control though they also result from the lack of materiality of the problems for those who have the power to change this scenario. In other words, the fact that those who control policies and resources do not experience the problems of lack of access that banish black and low-income people from the city serves to exacerbate this abyss.

“People decide on public policies based on their materiality… we only dream of what is visible to us. Nobody dreams of what they don’t even know exists. We only dream and only build from that place [that we can imagine]. That, in itself, dismantles the thinking of universality that many white people assume exists, which doesn’t reproduce itself only with thoughts, but also with policies,” says Rafaela. So, if decision-making spaces are mostly occupied by white people, “they will prioritize investing the budget they control in what is visible to them. They’re not going to think and elaborate on the demands of Jardim Gramacho when they’ve never set foot there. They will not prioritize the train when they’ve never been inside a station, when the most they’ve used in terms of public transport is the subway,” defended Rafaela Albergaria.

The various intersections between race, racism and mobility were addressed over three meetings promoted in October by ITDP. The idea is to debate the theme from researchers and black activists, who work on the topic of transport and access to the city. Check back next week for coverage of the second meeting.

Watch the Roundtable “Why Does Urban Mobility Need to be Anti-racist?” Here:

This is the first of three articles that cover the roundtable discussions of the Color of Mobility project. It is also the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

About the author: Born and raised in the favela of Fallet, in Santa Teresa, Central Rio, Jaqueline Suarez is a journalist and master’s student at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), in Niterói. Suarez is also a community journalist and independent documentary filmmaker.

About the artist: Born and raised in Complexo do Alemão, David Amen is co-founder and communications producer of the Roots in Movement Institute, a journalist, graffiti artist, and illustrator.