For original article in Viva Favela click here.

Lack of space has become a chronic problem in Rio’s favelas. It is evident that in the last few years buildings have grown taller. Dribbling the squeeze has become a constant concern. In most cases, there is just one solution: another floor, a Joker for anyone who needs to increase the size of their house, build a new room, or needs new work space. For residents, this is a triumph almost as important as home ownership itself.

Not coincidentally the construction project to “lift” the roof is traditionally organized as a party. The “laje,” (a new level, often in the form of a rooftop terrace or room), in recent years has begun to constitute an independent piece of real estate. It can be rented out or sold separately from the rest of the house. And its value has increased consistently. In the favela, expanding a house vertically is often the only option that allows an entire family to be housed. It is primarily during these times that people add a floor.

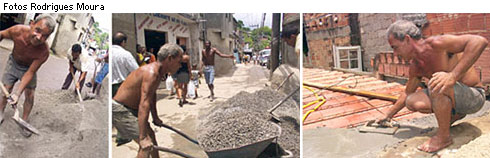

Adding a new floor is not complicated. Even those who are not professionals know the basics of the work. The mixture, which consists of washed sand and cement, becomes concrete when mixed with water, teaches stone worker Arlindo Manoel da Silva who lives in Alvorada in the Complexo do Alemão.

Everything ends in a party

But it’s hard work. Raising the roof is the most difficult part of home construction, and it requires strong, willing arms to do the work. For this reason, the process usually involves help from members of the family–especially when it is the owner of the house’s project–and friends. And to guarantee the energy of friends and family providing the intense manual labor for the project, the family prepares many dishes of heavy food: mocotó, beef-stew, Bahian mandioc. There must be enough beer. Especially because it is common the work ends in an all-night party.

Some make a point of helping despite not knowing the homeowner–or laje owner. It is not for no reason that the mutirão (collective action project)–would it be better to just call it a party?–of raising the roof has become a tradition in every and any favela.

After all that effort, when the space at the top of the construction project is concluded, it becomes a resource with a thousand and one uses: for barbecues, kite-flying, resting, hang hammocks, play dominoes, chess or cards with friends. On hot days significant numbers prefer to sleep under the stars than subject themselves to the heat indoors.

Lacking work space, brothers Ideraldo (40) and Artur Ribeiro Raimundo (41), both recently married, transformed their rooftop terrace into a workshop to produce doors, windows and covers in iron and aluminum. The business is prospering.

For the retired construction worker Antonio Pascoal Gomes, 51 years old, the addition of one more room would be extremely welcome. Only with the extra space would he be able to have a garage. The top then provides a play area for his grandchildren. The only thing missing to start the work is to set a date for the mutirão. “Friends always appear to help,” he says.

Unemployed, construction worker Lúcio de Mattos, 42, also understands this type of work. In the meantime, he does odd jobs throughout the community to be able to support his family. With his eleven year old daughter’s help, Priscila Jéssica Carvalho, he picks up work close to home. But, is this not really hard work for an eleven year old girl? Priscila says it isn’t. She likes to work with her father, and she is in charge of the lighter work. She uses a wooden wheelbarrow to transport the bricks. “She’s used to staying by my side,” he says. At the moment, the father and daughter are transporting a pre-made roof to a neighbor at the top of the community.

It is more enjoyable at the neighbors’

On top of the houses the kids have a field day. It’s their everyday playground. It is also a constant concern for mothers who worry about broken arms and legs when children fall from those heights. Like most boys from the favela, David Rodrigues, 12 years old, loves to fly kites. He admits though, “I prefer to fly kites on top of my neighbor’s laje… it is more enjoyable.” He also sweeps, washes the water tank on top of the roof, and keeps everything clean. Maybe this is why his mother, he says, is one of the few that doesn’t argue with him for staying out on top of the house all day. David is just one of the many boys who says that the laje is his favorite place.

And where else would teenage girls sunbathe? There’s no pool, but Priscilla Alves de Moura, 15 years old, drapes herself across the floor of her laje to catch some color. For her mother, Avaniza Conceiçnao Alves, 35 years old, like most mothers and wives, the climb to the top is simply to hang or fold clothes. On the clothesline, the clothes dance in the wind, and on days with lots of wind, even the tightest clips will do little to help. Whoever fails to clip their clothes securely to the line can be seen going from neighbor to neighbor collecting lost shirts and socks.

Eight years ago, Dulcinea Dias da Silva, 54 years old, decided to place a pool table on top of the roof. “I love to play pool, and the only place where the table could fit was on the laje,” she said. Her grandson, Leonardo Dias Batista (19), and his cousins loved the idea. But they weren’t the only ones. Since their laje is covered to protect drying clothes from getting wet in the rain, their rooftop has become the center of parties and games for the family. “During the World Cup and Carnaval, there isn’t another place to go. Children and grandchildren are used to coming here to watch the games and the samba parades,” she says. It is evident that everyone comes together on the laje.

Even the animals find space on the laje. Antonio Estevão de Lima, 65 years old, built a fancy canopy to cover and protect the birdcages of the birds he cares for so tenderly. Cely Alves, 50 years old, and Rafael de Almeida, 22 years old, like many other residents, prefer to leave the space free for the dogs. However, it is not always easy to find a house with a laje. Since it is greatly valued, it’s now common that the laje is independently marketed as a separate space from the house below. An independent entrance to the roof-top is all one needs to sell or rent the laje separately like any other property.

An example of this is the case of Ana de Souza Batista, 47 years old and married with three children. “After seeing the roof-top of the house that I wanted to buy, in Cruzeiro, I said I would build a room on top. The house only had two small rooms, a living room of about 3 square meters, a kitchen of 1.5 m x 2 m, and a bedroom of about 4 square meters on the second floor. However, the lady that sold me the house, said that I wouldn’t be able to build the room on top. The rooftop belonged to her brother. Since I needed the house I decided to buy it anyway,” she stated.

Later on, the brother of the past owner built a small room on top of the house so he could live there for some time. Afterwards, he sold the room to a third person, who then sold it to another person. Ana was only able to buy the rooftop when it was put on sale for the fifth time. “Only then were my two children and mother able to have a room for themselves, and my husband and I, and our two year old baby were able to have our own room as well,” stated Ana. And shortly thereafter, she completed her thought: “The laje was finally ours…”