This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” It is also part of a series created in partnership with the Center for Critical Studies in Language, Education, and Society (NECLES), at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), to produce articles to be used as teaching materials in Niterói public schools. Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

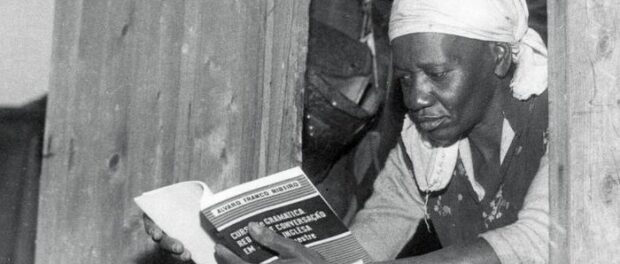

In this excerpt from the book Bitita’s Diary, in a chat with her grandfather, author Carolina Maria de Jesus reveals a Brazil we pretend not to know:

“My grandfather’s eight children couldn’t read. They were manual laborers. My grandfather was sorry that his children hadn’t learned to read and used to say: ‘No, it wasn’t due to negligence on my part.’ It’s just that at the time his children were supposed to be studying, Afro-Brazilians weren’t allowed in schools. So, when you start school, study hard and strive to learn.”

The last Western nation to abolish slavery gave no decent societal conditions to its Afro-Brazilian population. The sum of these factors results in unequal access in all spheres.

“My name is Denise, better known as Denise Crioula, an Afro-Brazilian woman from the periphery and a teacher of the Rio de Janeiro public school system. My path in education started very early on. I learned to read when I was four. I started school in the second grade and stayed on until I was 16, when my parents separated, and I had to work. Working and studying at the same time is very difficult, very demanding. And at that moment the greatest need was work, not study, to help out my mom. So, I got a job. When I was 19, I got married and had two children. As soon as I split up with my husband, I went back to school. I went back to school when I was 31. I finished high school and went straight to college.”

The story above was told by Denise Crioula, a teacher who lives in Paciência, in the West Zone of Rio de Janeiro and who found herself having to drop out of school during her life’s journey. For over ten years, she has been involved with psycho-pedagogical assistance through Social Conquest, an NGO that reduces inequality through education.

In 2019, 10 million Brazilian youth left school without finishing their basic education. Of these, 71.7% are Afro-Brazilian. Working is synonymous with survival, and, in the Brazil of the coronavirus pandemic, survival has become even more difficult.

There are many reasons that push a young person out of school. According to the study “Facing the Culture of Failing at School,” conducted by UNICEF, more than 5 million Brazilian children and adolescents did not have access to education in 2020. This reality is reflected in favelas, which have seen over half of their kids miss school during the pandemic according to a survey conducted by the Favela Data Institute, in partnership with the Locomotiva Research Institute and Central Única das Favelas (CUFA).

What Is School Flight? Family Cycles Dictate It

At the outset, we must establish the difference between the concepts of school dropout and school flight in the Brazilian context. When a student stops attending classes during the school year, it is normally said that they “dropped out of school.” However, in the situation where a student who either failed or passed the previous grade does not enroll to continue their studies the following year, the term “school flight” is more appropriate. Both, however, should be equally understood as complex social phenomena, resulting from several structural social struggles.

At the outset, we must establish the difference between the concepts of school dropout and school flight in the Brazilian context. When a student stops attending classes during the school year, it is normally said that they “dropped out of school.” However, in the situation where a student who either failed or passed the previous grade does not enroll to continue their studies the following year, the term “school flight” is more appropriate. Both, however, should be equally understood as complex social phenomena, resulting from several structural social struggles.

Structural racism dictates many of our society’s disparities and influences educational and socioeconomic indicators. Data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics’ (IBGE) last Continuous National Household Sample Survey (Continuous Pnad), conducted in 2015, show how family context influences the decision to drop out of school. In Rio de Janeiro, for example, research data show that when the student’s family is headed by a white male, holding at least a high school diploma, earning a good income, and living in the urban area, the probability of this student attending school regularly is approximately 90%. For families headed by Afro-Brazilian women, who are illiterate and rural, the maximum school attendance rate is 50%.

This reality highlights the socioeconomic shocks these youth are constantly faced with. After all, have you ever skipped school because you didn’t have the bus fare? Or were there ever times when you only had one meal to sustain you for a whole day?

Teacher Robson Abreu, member of the School Community Council (CEC)—an advisory board of Rio’s municipal government that aims to promote constant and effective integration between school, family and community—explains what actions, taking into account the existing structures of the schools they work in, principals can take as preventive measures to reduce dropout and school flight levels:

“The family bond is crucial even in trying to understand what is behind a student’s absences. For this reason, one of the things we do is contact the family, bring the family into school, talk things out, try to find solutions. During the pandemic, [school flight] has increased enormously, because in addition to students who were already in the habit of missing school, other factors are now affecting attendance [in person because of the pandemic and online due to lack of access to technology]. In such cases, school flight risks are even greater. Arrangements are also being made to bring these students into school, to work with them every step of the way to provide them, in the absence of Internet access, with printed material, so that they are not alienated from their learning rights during the pandemic. In other words, we try to do all this preventive work, but the pandemic undoubtedly made it even harder to prevent school flight and dropout rates.”

Analyzing the most varied research data, it is clear that the racial debate is a key point of the school flight topic. And it is important to understand how the racial issue has been addressed in schools and by public policies. Abreu tells us as well what it’s been like to discuss the issue with students and families:

“Utilizing debates about race as a pedagogical tool is still far from the ideal, isn’t it? It ends up being quite limited to individual actions by teachers who hold a strong commitment to these topics. Depending on the school unit, it may or may not be embraced by the community. But, as far as I know, there is no practice or policy of pedagogical practice which truly encompasses the relevance of dealing with the theme and the vacuum left by this omission. However, I also do see progress. I see some appreciation for black culture beyond specific periods such as Black Awareness Month. We do observe initiatives that end up being multiplied. With families, it is difficult since, quite often, they themselves are unaware of the importance of the racial debate and place themselves as spectators of the process. But this is also changing because many students have realized the importance of discussing, of engaging as a group to change not only paradigms, but mainly the passive acceptance [of racism]… this is something that really needs to change.”

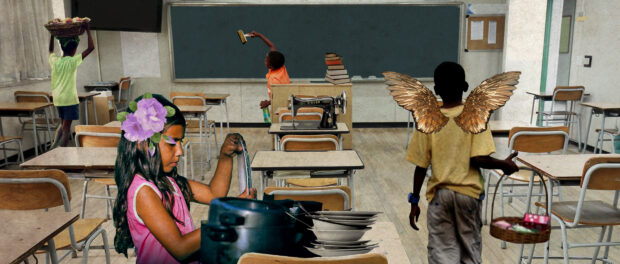

Following students’ and families’ individual trajectories is essencial to offer them the necessary tools for their return to school. With this in mind, performing arts teacher Alessandra Biá developed a project called ELA—Liberatory School of Arts. Starting at the Paulo Freire Municipal School, in Vila do Pinheiro, in 2019, ELA hit the streets of Complexo da Maré. Biá, as she is known, reenacted the tragedy of the murder of Agatha Félix, who was shot inside a VW Bus in Complexo do Alemão. When it occurred, the tragedy deeply affected Biá’s students, and she came up with the idea of turning ELA into an itinerant education tool.

“I arrived with my VW Bus and the children showed me the best place to park. At first, we stopped at a random spot, then they took me to a wooded area where we ended up staying for a long time. They themselves would open up the VW Bus and take out the educational tools. The VW Bus contains visual arts and music material, a toy library, material for DJing, and assorted creative equipment for this type of work. Ultimately, they’d set up their own classes and would teach them themselves. I basically acted as a facilitator in the middle of all this. One student taught the other and from then on unimaginable things would happen.”

View this post on Instagram

Written on the van: “Say no to racism!! Good morning!”

Going on a little pedagogical stroll

The work developed by Biá is in tune with another school flight marker, which is students’ disengagement from school. The decision to take flight does not happen instantly: it is, in fact, a very long process. The challenge is to develop and implement active retention practices, adaptable and tailored to each reality. The Liberatory School of Arts has been stirring a passion for knowledge and, consequently, sparks an interest for knowledge in Maré youth. According to Biá: “ELA has always had a relationship with school flight because it is itinerant, it belongs to the street, it is approachable, and speaks the language of freedom. All these characteristics help people approach ELA naturally. It’s not an obligation: ELA is a weekend school. Everyone wants to study on the weekend! Me, I usually play. So, unintentionally, we end up heading towards a space of knowledge, which they often don’t even believe in anymore, because they think it’s boring, they think it’s not suited to them.”

Although the vast majority leave school for socioeconomic reasons, almost half of young people who take flight from school do not work. Which also means that, for some students, school simply ceased to be an attractive or even safe place. These young people are not easily absorbed into the labor market as they have neither skills nor experience. They exit classrooms to face unemployment, informal work and, increasingly, hunger.

As an example, if a student is transgender and is subjected to transphobic bullying at school, the chances of that student taking flight is approximately 82%, while still in elementary school. These data were obtained from research conducted by public defender João Paulo Carvalho Dias, who is also president of the state of Mato Grosso chapter of the Brazilian Bar Association’s Committee on Sexual Diversity. The paths that lead to lack of interest and feelings of insecurity in the school environment are many, such as negative interactions with teachers and classmates, learning difficulties, repeating a grade, prejudice, teenage emotional issues and not receiving individualized and constant pedagogical attention.

Still A Lot of Work Ahead

The first major step is to develop a listening methodology that is both active and focused on existing needs, especially regarding the infrastructure of many public schools. Secondly, it is imperative to understand that schools form a community which should engage and welcome students’ families and develop actions that focus on discussing racial issues both with family members and students.

In 2021, in a country numbering over 600,000 dead, coronavirus displaced youth from the school’s physical environment due to mismanagement of the immunization drive among the population, and the federal government sabotaging the fight against the pandemic. It took way too long to guarantee students’ safe return to classrooms in 2021.

It is important to remember that quality education is a constitutional right in Brazil. It is a pledge of the United Nations‘ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which set targets to be reached by 2030.

Unfortunately, Brazilian youth, especially those in public schools, have been left in the dark, once again paraphrasing writer Carolina Maria de Jesus‘s diary, Child of the Dark. School flight is this place of discomfort—and we know full well who in our population feels this discomfort. We can already envision the rotten fruits yielded by the lack of care and the omissions of a genocidal health policy, of necropolitics as a public policy for the pandemic, on the education of Afro-Brazilian and favela youth.

“Brazil needs to be run by someone who has already experienced hunger. Hunger is also a teacher. Those who go hungry learn to think about others and about children.” This truth exalted by Carolina Maria de Jesus in the 1950s still resonates with the same strength today. We will only move forward when our own occupy political decision roles. It is necessary that Afro-Brazilian, indigenous people and favela leaders advance, but to do so, we must break the logic of reproducing the existing privileges of whiteness. Public education must be defended against disinvestment and destruction. An anti-racist, accessible, and quality public education is our greatest weapon to address Brazilian inequalities.

Accompanying Podcast in Portuguese Available Here:

About the author: Cleyton Santanna hold degrees in journalism and screenwriting from UFRRJ and the CriaAtivo Film School. He uses his YouTube channel to address oddities, ancestry, and Afro-Brazilian culture. In 2017, he produced two documentaries: “Entre Negros” (Between Blacks) and “Tudo Vai Ficar Bem” (Everything is Gonna Be OK), and was recognized as a screenwriter in 2018 by the Creative Economy Network for the short “Vandinho.” He is currently a communicator for The Museum of Tomorrow and hosts the Influência Negra podcast.

About the artist: Born and raised in Complexo do Alemão, David Amen is co-founder and communications producer of the Roots in Movement Institute, a journalist, graffiti artist, and illustrator.

This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.