This is the second of three articles that cover the roundtable discussions of the Color of Mobility project. It is also the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

How do we build transit that is just and high quality for all? This was the topic of the second roundtable held on October 20 by the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP), in partnership with the São Paulo Association of Urban Cyclists (Ciclocidade) and Pedal in the Hood. The meet-up is part of the Color of Mobility project, whose objective is to make visible the effects of racism in the way the black and peripheral population transits through Brazilian cities. For this second meeting, participants were invited to reflect on how the quality of public transit restricts access to rights and opportunities.

Luana Costa, social media and community organizing consultant for the Our Belo Horizonte Movement, and architect and urban planner Sarah Esli, were invited to speak on the subject. Costa and Esli are black women who study mobility from the perspective of their own life experiences in their home territories. Costa is an educator and popular communicator with a graduate degree in human and citizen rights, and co-author of the article “Black Youth are Going Places,” published in the book Anti-Racist Mobility. Sarah Esli created the platform Roads and Rhymes, that proposes urban studies having hip-hop culture as a point of departure. She lives in the city of Natal, in the Northeastern state of Rio Grande do Norte.

Luana Costa, social media and community organizing consultant for the Our Belo Horizonte Movement, and architect and urban planner Sarah Esli, were invited to speak on the subject. Costa and Esli are black women who study mobility from the perspective of their own life experiences in their home territories. Costa is an educator and popular communicator with a graduate degree in human and citizen rights, and co-author of the article “Black Youth are Going Places,” published in the book Anti-Racist Mobility. Sarah Esli created the platform Roads and Rhymes, that proposes urban studies having hip-hop culture as a point of departure. She lives in the city of Natal, in the Northeastern state of Rio Grande do Norte.

The roundtable was moderated by Lorena Freitas, a doctoral student in Transportation Engineering, and Coordinator of Mobility Management at ITDP. Rincon Sapiência’s poetry in music kicked off the event. From the experience of a black peripheral man transiting through the city of São Paulo, the rapper wrote the words to the song “Public Transit”:

[…] I get on the railcar, I’m chillin’ for real

The trip is collective, but also individual

Everyone tries to keep their mood at a high

Jammin’ to music, brewing ideas, reading the paperRush hour, the subway’s packed, you feel sick

Workers have to suffer even before they get to work

For the poor, hardship is real

Freedom belongs to the cars that speed down the highway […]

Like Rincon, Esli also believes that the use of public transit is a personal experience. That is why it is crucial to reflect on who it is that plans and who it is that uses these modes. “In my view, talking about the right to the city means talking about life experience and living. Experiences don’t repeat themselves from one person to the next, even when these people are occupying the same space, at the same time. An experience does not repeat itself,” argues Esli, who also says: “Race, gender, sexuality and age are aspects that will always make our experiences different.”

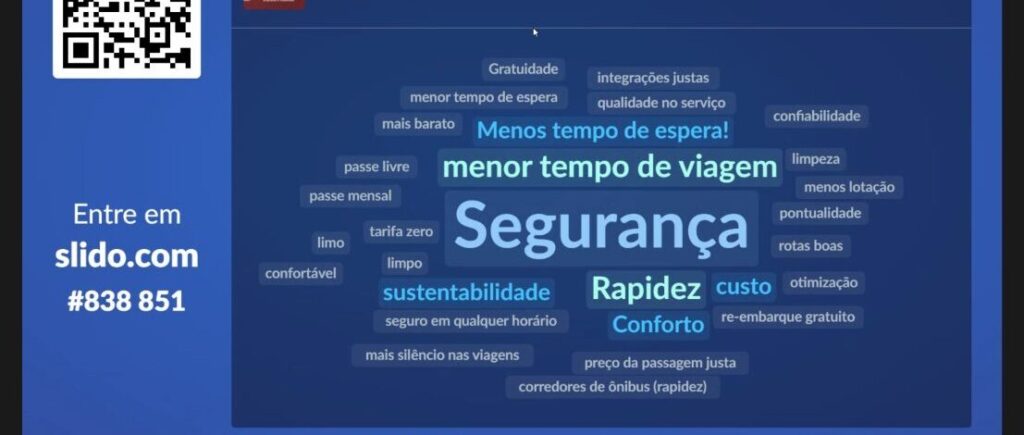

The issue of safety in mass transit is a good example. Safety was mentioned by participants as one of the main factors in deciding whether to take mass transit. Although the issue was pointed out by both men and women, and although it covers more than just the vehicle’s interior to include the route taken to stops, women’s concerns are quite different from men’s. The fear of being harassed or sexually assaulted, for instance, is mentioned as an important issue for women. Therefore, vulnerability generated by gender brings about distinct concerns and experiences.

“In thinking of experiences in public transit, a child gets to go under the turnstile. The elderly get in through the back. Students show their bus passes. Nowadays, drivers themselves collect the fare; they are drivers and fare collectors. So, a same bus creates different experiences, even if the route is the same and people are getting on and off at the same stops,” illustrates Esli. The experience will also be determined by the territory and, consequently, by the profile of users. The supply of transit and its quality restrict access and influence the possibilities of leisure, work, education and much more.

To explain this, Esli showed maps created by the Access to Opportunities project, produced from research coordinated by the Institute for Applied Economic Research (IPEA). The project estimates the population’s access to work, health services and education by transit mode. In this manner, the inequalities created or highlighted by mobility become visible.

Using maps for Natal, Esli shows that residents of the city’s central zone are able to access opportunities by walking approximately 15 minutes, while those who live in peripheries need transport to have this access. “In speaking of peripheral territories, of racialized populations, we are talking, specifically, of buses, trains, bicycles and motorbikes, at least here in Natal,” says Esli. Therefore, the absence or precarious supply of transit services restrict or even prevent transit and access to opportunities and rights.

Esli mentions the purely quantitative nature of the studies and analyses that shape how urban mobility systems are structured as one of her greatest discomforts. “A lot of weight is given to quantitative studies and analyses, which are certainly important for creating and defending public policies. But in my opinion, charts are not enough for us to understand problems and imagine solutions that take into account the right to the city and mobility for everyone.”

According to the researcher, in order to think of real improvements, we must discuss mobility and the planning of modes with those who actually use public transit. Surveys need to prioritize users’ experiences and profiles: “We need to get to know those who use public transit to then build a path.”

The inclusion of race and origin of users in the debate on mobility, as pointed out by Esli, was what led Costa to join the Our BH Movement. Living in the North Zone of Belo Horizonte, in the state of Minas Gerais, Costa’s personal mission was to “burst the downtown BH bubble” and reach the peripheries.

She describes how the post-slavery period in Brazil was not followed by policies of reparations and equity, therefore producing an unequal society whose forms of organization are rooted in structural racism. The establishment of favelas and the conditions of transit accessed by this peripheral population and, in particular, by Afro-Brazilians, are integrally influenced by this history. “I find myself unable to reflect on transit as a right for a population that does not have its minimum rights as citizens upheld, ” argues Costa, making clear that we still have a long way to go.

“Where I’m from, you can’t really talk about quality public transit,” says Costa, referring to how difficult it is to bring the issue into discussion in peripheries. She lives approximately 20 kilometers from the city center and explains: “My whole life, my whole experience, as is the case of many people who live in this part of town, has been to be removed from places, far from opportunities, far from jobs, far from school, far from the health center or from the hospital.” Reciting an excerpt from the Elisa Lucinda poem that opens the book Anti-Racist Mobility, she sums things up by saying: “we are far from the dream.”

In Costa’s view, in Brazil, we can talk about mass transit but not about transit that is truly public due to the proprietary aspect of the system, which prioritizes profit. Like Sarah Esli, Costa sees the participation of users—especially that of the peripheral population that is more dependent on public transit—as crucial. “If we want to discuss the issue properly, we need to occupy spaces. How can we guarantee people’s participation in these processes? When we look at Belo Horizonte and at other Brazilian capitals, it’s plain to see that this participation is not guaranteed!” she says.

The full participation of users stumbles on a series of issues, as exemplified by the researcher. Costa recounts a few of her experiences in forums and committees that discuss the topic: “Do not assume that a black person showing up at these places means that this voice will be heard. Quite the opposite. Every time I’ve had the chance to be in one of these places, I was mowed down. For starters, I’m not even seen at times. Then, when I am seen, I am perceived as a strange, suspect element, which is the way black people are viewed in our society. And as for a voice? Having a voice is a different story.” Taking the opposite approach, Costa explains that the Our BH Movement tries to coordinate networks and bring people together to build new spaces of discussion on mobility, including the possibility of taking the debate from the city’s central region to peripheral neighborhoods.

Esli and Costa point out other factors that limit or even prevent users from participating in the mobility debate. One example is the reduced number of public consultations before drafting a plan. Esli recounts that, in Natal, many residents are not even made aware of such meetings and that many take place in the late afternoon, when many are still at work or in transit. Costa, on the other hand, calls attention to the highly technical nature of discussion on the topic, which ends up driving people away from discussing it. “It seems that if you don’t have a degree that somewhat addresses the issue of mobility, you’re not allowed to discuss it. It’s something that affects you so much, every single day, so why can’t you talk about it?” questions Costa.

Watch the Roundtable “How Do We Build High-Quality, Just Transit For All?” Here:

This is the second of three articles that cover the roundtable discussions of the Color of Mobility project. It is also the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

About the author: Jaqueline Suarez was born and raised in the favela of Fallet, in Santa Teresa, Central Rio. She is a journalist and master’s student at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), in Niterói, and an independent documentary filmmaker.

About the artist: David Amen was born and raised in Complexo do Alemão, is co-founder and communications producer at the Roots in Movement Institute, a journalist, graffiti artist, and illustrator.