This is the third of three articles that cover the roundtable discussions of the Color of Mobility project. It is also the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

“Cycling as resistance: how racism affects mobility by bike” was the subject of the third and final roundtable held on October 27 by the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP), in partnership with the São Paulo Association of Urban Cyclists (Ciclocidade) and Pedal in the Hood. In this latest meeting, participants reflected on the main challenges that restrict Brazil’s black, peripheral, or low-income people from moving by bike.

The three roundtables are part of the Color of Mobility project, whose objective is to make visible the effects of racism in the way the black and peripheral population transits through Brazilian cities. At the first event, the close relationship between racism and the organization of urban transport systems was addressed. At the second, the discussion was about the quality of public transport and its impact on access to services and opportunities.

At all three roundtables, the participants were Afro-Brazilians who study and participate in movements and collectives engaged with mobility in different cities across Brazil. The routine absence of black and brown people living in peripheral areas and on low incomes in spaces for debate, and from positions of decision-making, was pointed out across the events as one of the main obstacles in identifying the real demands of the population that uses and depends on transport systems. This also includes bicycle transport, as participants in the last roundtable discussed.

At all three roundtables, the participants were Afro-Brazilians who study and participate in movements and collectives engaged with mobility in different cities across Brazil. The routine absence of black and brown people living in peripheral areas and on low incomes in spaces for debate, and from positions of decision-making, was pointed out across the events as one of the main obstacles in identifying the real demands of the population that uses and depends on transport systems. This also includes bicycle transport, as participants in the last roundtable discussed.

Carlos Greenbike, founder of the Cycle Queimados Association and Jamile Santana, cofounder of the Afro Cycle Collective Mobilization Network participated in the debate. Greenbike started his project in the city of Queimados, in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region, and has traveled to many countries, taking Cycle Queimados’ name and struggle with him. The project aims to promote the bicycle as a tool for social transformation, with a focus on generating work and income, promoting citizenship and reducing inequality.

Before cofounding the Afro Cycle project, Santana participated in the creation of another initiative called Black Girls Go By Bike, which taught black women how to ride bicycles and encouraged them to use them as a mode of transport. From this experience came the desire and need to look at this subject from the perspectives of race and gender, which Santana took to university and turned into research. In 2020, Afro Cycle was born, a project which seeks the social transformation of peripheral, rural and quilombola communities that are segregated from city centers of cities in the Recôncavo Baiano, the region that surrounds Salvador in the state of Bahia. (Quilombos are communities comprised of descendants of enslaved people in Brazil who still live on their ancestral lands.)

Before cofounding the Afro Cycle project, Santana participated in the creation of another initiative called Black Girls Go By Bike, which taught black women how to ride bicycles and encouraged them to use them as a mode of transport. From this experience came the desire and need to look at this subject from the perspectives of race and gender, which Santana took to university and turned into research. In 2020, Afro Cycle was born, a project which seeks the social transformation of peripheral, rural and quilombola communities that are segregated from city centers of cities in the Recôncavo Baiano, the region that surrounds Salvador in the state of Bahia. (Quilombos are communities comprised of descendants of enslaved people in Brazil who still live on their ancestral lands.)

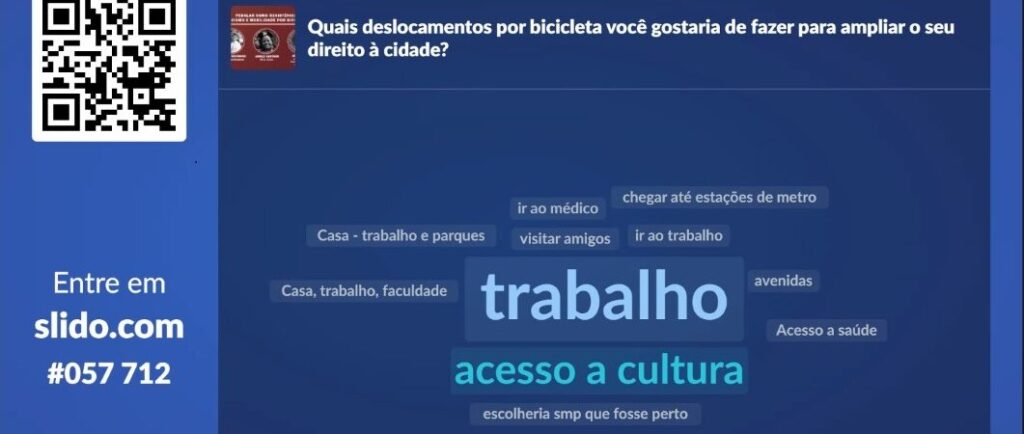

The moderator of the latest roundtable was Jo Pereira, director of Ciclocidade. She started the discussion by asking those present: “What journeys would you like to take by bicycle to expand your right to the city?” Going to work, accessing parks and cultural infrastructure, as well as health centers, were the main responses. She called attention to the different experiences during these journeys, especially for young black people, the group that experiences the most violence in public spaces.

Starting with structural racism around mobility, Pereira asked: “What can make this anti-racist mobility visible?” As Greenbike from Cycle Queimados sees it, the insistence and persistence of collectives and activists are the main element in the fight for anti-racist mobility. Over the years, the collective’s work has enabled him and other people to participate in events and discussions on the subject in Brazil and abroad. On many of these journeys, as he explains, there have been various situations in which racism was explicit.

Greenbike remembers an episode which happened in 2019, when he participated in an international conference in Dublin, Ireland. “When the event ended, I went to a pub with a group from São Paulo and some people from other countries. The whole white group went into the pub and security stopped me from entering. The group came back out, talked to security, called the manager, and they still didn’t let me in. We all had to leave and go somewhere else, since I wasn’t allowed in because I am black,” recalls Greenbike. He continues: “What makes this mobility, this anti-racist movement possible is our insistence, our persistence and, over time, we have been breaking open these spaces.”

Pereira adds: “When we better our vocabulary, when we are in places that we build so we can also be in them, we are still questioned.”

Santana, on the other hand, points out the existence of racist mobility as another path to the visibility—and necessity—of anti-racist transit. “A totally segregationist city is built, where the right to transit is denied to the black population, who occupy the majority of places which are at the margin of resources,” she observes. A good example of this is rush hour, which defines a time for arriving and another for leaving work and, as a consequence, delimits the amount of time that certain people are welcome in the central areas of cities.

Like Greenbike, Santana also highlights the absence of black people in spaces for debate, including in meetings organized by civil society. She recalls one of the first conferences on the topic she took part in, in 2016, where almost all participants were white: “I could count on the fingers of one hand how many black people were occupying that space.”

Like Greenbike, Santana also highlights the absence of black people in spaces for debate, including in meetings organized by civil society. She recalls one of the first conferences on the topic she took part in, in 2016, where almost all participants were white: “I could count on the fingers of one hand how many black people were occupying that space.”

Underlining the absence of diversity and occupying theses spaces are, according to Santana, mechanisms for confronting the racist structure of mobility. She also mentions activities directed at teaching the black and peripheral population how to cycle, setting up bike racks, campaigning and communicating with people and strengthening self-esteem in these territories. “The idea is that we denounce these spaces more and more and demand our rightful place,” summarizes Santana. She observes that: “2020, 2021 were years that I managed to see a much greater number of roundtables discussing anti-racist mobility, racist mobility, mobility in peripheral areas, putting more black movements and people on the agenda.”

Next, Jo Pereira shared an experience she had in 2019 when she was invited to talk at a big event on mobility. “I was tested in every possible aspect: regarding my ability, the hairstyle I would wear to the event, what clothes I would wear to the event, what I was going to present at the event… In the presentation I gave, I started out with Maria Carolina de Jesus and the communication officer asked, ‘but who is this woman?’ I was very hurt that day, but I went on and said who that woman was and who we are,” says Pereira about the racism she experienced. She reminds us that the fight against racism is collective and, above all, that it is not the sole responsibility of black people.

“For those of us that are in collectives and institutions, cycling also becomes a place of political activity,” recognizes Pereira. “The majority of those who cycle in this country are black and peripheral people, but these are not the people being thought of in public policies on urban mobility,” she points out. Based on this, she asked about the challenges the collectives face to guarantee the continuation of the movement and of the groups themselves.

“For those of us that are in collectives and institutions, cycling also becomes a place of political activity,” recognizes Pereira. “The majority of those who cycle in this country are black and peripheral people, but these are not the people being thought of in public policies on urban mobility,” she points out. Based on this, she asked about the challenges the collectives face to guarantee the continuation of the movement and of the groups themselves.

For Santana, the strengthening of agendas and of the collective itself is in recognizing peer groups. That is, talking and getting together with movements and people who have similar objectives. Combining agendas and proposals is, in Santana’s opinion, an act of co-creation, as is seeking to strengthen the collective through the community itself. “I see that there are many black mobility movements, many cycleactivists involved in teaching children to cycle… Teaching children, teaching women, this a widespread movement,” defends Santana.

She sums up: “The more we come together and understand our common enemy, which is this predatory development, and we understand our strategies for resilience and revolution to confront it, the stronger we grow.”

Cycle Queimados’ initial proposal was to think about mobility for the city of Queimados. However, as Greenbike explained, working separately from the municipal government didn’t work. The city entered the national agenda through the issue of public security: in 2018, Queimados was considered the most violent city in Brazil by the Violence Atlas, research carried out by the Institute for Applied Economic Research (IPEA) and by the Brazilian Forum on Public Safety. The next year, the same research again pointed to the municipality as one of the five most violent in the country.

Access to education and employment are other problems confronted by the population, the majority of whom end up finding work far from home: “we have the second longest home-work travel time [in the country], we are a commuter town where the majority of people travel three hours to get to the capital; three hours there and three hours back,” explains Greenbike, citing figures from 2010, taken from the last Census carried out by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE).

In response to this situation, the project began trying to involve young people in its activities, with a focus on training and generating income for this group. According to Greenbike, the big problem in continuing this work is the lack of support. “Personally, I dedicate myself 100% to Cycle Queimados and to cycling, but when I look around, I don’t have anyone who also commits themselves 100% because we don’t have any financial resources. How can I guarantee the demands of society if our [demand] is not met?” he asks.

Greenbike is intent on generating employment and income, especially for those who make the Cycle Queimados collective happen, so as to guarantee a more solid foundation. “What we really need—the institutions, the collectives—is for businesses and grants to take this territory into account, to look at the collectives that are already active in that area,” he argued. Greenbike explained that sometimes institutions outside the area receive resources to carry out work that local collectives could do or are already doing, although without financial support. “Everyone says that what we do is super cool, but that’s not enough to make ends meet at the end of the month,” he concludes. Guaranteeing the presence of black, peripheral people in spaces for debate and decision-making on the topic is the first step to making demands that truly respond and guarantee this population’s access to urban mobility and, in particular, to traveling by bike.

Watch the Roundtable “Cycling as Resistance: How Racism Affects Mobility by Bike” Here:

This is the third of three articles that cover the roundtable discussions of the Color of Mobility project. It is also the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

About the author: Born and raised in the favela of Fallet, in Santa Teresa, Central Rio, Jaqueline Suarez is a journalist and master’s student at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), in Niterói. Suarez is also a community journalist and independent documentary filmmaker.

About the artist: Born and raised in Complexo do Alemão, David Amen is co-founder and communications producer of the Roots in Movement Institute, a journalist, graffiti artist, and illustrator.