This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” It is also part of a series created in partnership with the Center for Critical Studies in Language, Education, and Society (NECLES), at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), to produce articles to be used as teaching materials in Niterói public schools. Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

This year, Law 10,639/03, which establishes requirements for the teaching of Afro-Brazilian history and culture in schools, turns 18. According to the legal text, every school in Brazil should teach “the History of Africa and Africans, the struggle of black people in Brazil, Afro-Brazilian culture, and the contributions of black people in forming national society, including social, economic, and political areas relevant to the History of Brazil.” These topics should all, according to the law, be present in school curricula, “in a multidisciplinary and intersectional way.”

The law was an achievement of the Black Movement and of other anti-racist movements in Brazil. It seeks to recognize and value the contributions of African culture and Afro-Brazilians in building the country. The educational system is one of the main re-producers of structural inequities and racism in society, but it could instead be instrumental in improving popular perspectives on race. It is in this sense that the law seeks to bring about change.

But as it comes of age, how has this law matured? Is it possible to say that it has been well implemented, especially in schools in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, where the majority of the population is black? In talking with researchers and teachers who work day-to-day in Rio’s municipal school system, we see a long road ahead to better institutionalize the teaching of Afro-Brazilian history and culture.

Individual Initiative vs. a Formalized Teaching Plan

Alessandra Pio is a professor at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), but for a long time worked in elementary education in Rio de Janeiro. She points out that one of the first obstacles in ensuring the effectiveness of Law 10,639/03 is the difficulty of measuring implementation. In other words: monitoring whether the law is being upheld. “The law is the law; you either apply it or you don’t. When we read between the lines, to ‘apply the law’ has [simply] meant having a black teacher organize a Black Awareness Month event in November at their school… But that’s not applying the law,” says Professor Pio.

Alessandra Pio is a professor at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), but for a long time worked in elementary education in Rio de Janeiro. She points out that one of the first obstacles in ensuring the effectiveness of Law 10,639/03 is the difficulty of measuring implementation. In other words: monitoring whether the law is being upheld. “The law is the law; you either apply it or you don’t. When we read between the lines, to ‘apply the law’ has [simply] meant having a black teacher organize a Black Awareness Month event in November at their school… But that’s not applying the law,” says Professor Pio.

Ensuring that educational institutions are engaging with Afro-Brazilian culture ends up the responsibility of black teachers themselves, who find themselves in the position of having to urge their peers to implement the law. “It seems that the law is only intended to be carried out by black people. The responsibility of white people is optional. So, at the school level, they demand that we solve the implementation of Law 10,639,” adds Pio.

Silvia Barros is coordinator of the Center for Afro-Brazilian and Indigenous Studies in Rio de Janeiro (NEABI-RJ). She gives specialized teacher training in ethnic-racial studies, working with people from different parts of Rio. Barros also notes the solitary struggle of teachers who try to apply the law in their schools, but without any support. “This feeling of doing it alone or of being the reference in the school: ‘talk to so-and-so because he’s the one who knows about these issues,’ creates a lot of responsibility for just one person,” she says.

Silvia Barros is coordinator of the Center for Afro-Brazilian and Indigenous Studies in Rio de Janeiro (NEABI-RJ). She gives specialized teacher training in ethnic-racial studies, working with people from different parts of Rio. Barros also notes the solitary struggle of teachers who try to apply the law in their schools, but without any support. “This feeling of doing it alone or of being the reference in the school: ‘talk to so-and-so because he’s the one who knows about these issues,’ creates a lot of responsibility for just one person,” she says.

The individual actions of black teachers trying to implement Law 10,639 reveal how many schools do not embrace the teaching of Afro-Brazilian history and culture in their teaching plans as they should. “Many times, the teaching plan is a ‘big brick’ [a very big book] that just sits on the coordination room shelf. Nobody touches it, nobody sees it. It’s something that people aren’t involved in creating. Schools are hierarchical, they like hierarchical structures,” says Pio.

Barros mentions the need for more actions that are broadly and deeply rooted in ethnic-racial studies. “There are many elements preventing effective, anti-racist change to expand and take root in all areas of a school, both in the formal curriculum and in everything that exists inside the school. Even if it is not explicitly [part of the curriculum, we need to consider] the organization of classrooms, posters that hang on walls, conversations and speeches given, the school lunch, what is eaten, who the students are that receive that food, who are the people who produce that food. All these elements that make up a school community are still very far from real change,” she concludes.

Rosária Diniz has worked in municipal public education for 26 years, both as a teacher and a coordinator in five schools. Having taught in all of them, and worked as a pedagogical coordinator in one, Diniz currently teaches in a public school in Taquara, in the West Zone of Rio. With her vast experience, she sees that there are insufficient institutionalized actions, which depend less on the individuals making up the school staff, but that are instead implicit in the intersectional and multidisciplinary way curricular subjects should be taught, as is required by law. Further institutionalized actions are needed to actually implement the teaching of African and Afro-Brazilian history in Rio’s public schools. “What I have come to realize from my own path is that, of all the five schools I’ve worked at, the only one that has incorporated this issue into its formal teaching plan is the one I’m at now. The issue normally has a lot more to do with a teacher’s point of view than with an institutionalized standard,” she says.

Rosária Diniz has worked in municipal public education for 26 years, both as a teacher and a coordinator in five schools. Having taught in all of them, and worked as a pedagogical coordinator in one, Diniz currently teaches in a public school in Taquara, in the West Zone of Rio. With her vast experience, she sees that there are insufficient institutionalized actions, which depend less on the individuals making up the school staff, but that are instead implicit in the intersectional and multidisciplinary way curricular subjects should be taught, as is required by law. Further institutionalized actions are needed to actually implement the teaching of African and Afro-Brazilian history in Rio’s public schools. “What I have come to realize from my own path is that, of all the five schools I’ve worked at, the only one that has incorporated this issue into its formal teaching plan is the one I’m at now. The issue normally has a lot more to do with a teacher’s point of view than with an institutionalized standard,” she says.

Teacher Training

In partnership with UNESCO, the Ministry of Education conducted a survey in 2012 that revealed the main barriers in advancing Law 10,639/03. One of the factors indicated is a lot of misinformation or ignorance about the change in the Law of Directives and Bases of National Education (LDB), along with other documents that affect this change. One of the institutions involved in conducting this research was NEABI. Silvia Ramos explains where this ignorance stems from: “Today I understand that curricular changes should be made in undergraduate courses. What I see is that some topics are included as extensions, just to say that certain information is covered. In the School of Modern Languages, we’ve been fighting for all majors to have enough content on African literature. And I see this happening in other academic areas as well.”

Alessandra Pio has also diagnosed a need to change university curricula. “There is a common racist pushback claiming that: ‘including more Africa will undermine the curriculum.’ We are just so colonized! This argument of not giving Law 10,639 an institutional status is because racism rejects [African History] as knowledge worth being institutionalized,” she says.

Religious Racism in Public Education

The growth of the evangelical movement in Brazilian society, especially the neo-Pentecostal sector, can be observed in several spheres, including schools. This has been one of the main challenges in enforcing the teaching of Afro-Brazilian history and culture: resistance from parents, teachers, or school boards that reject the faith, culture, and history of black people as demonic.

“Religious racism is a very strong force, especially in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense, in the peripheries. The neo-Pentecostal movement has invaded schools in an irreversible way, I think… If we start to enforce the law such that people who do not implement it suffer the necessary sanctions, then we can start to have a more equitable dialogue,” says Alessandra Pio.

Repressed and criminalized, black and favela culture have always been seen as an issue for the police. Even today, there is fear of black culture and of black religiosity. According to Barros, in schools, this manifests itself mainly through evangelical parents: “but obviously it has to be talked about because there is no way to disconnect one thing from the other. Many times, there is religious racism coming from the school itself, where there is rejection, and from guardians, who are inclined towards other religious denominations and don’t want their children to have contact [with African cultures and religions].”

Repressed and criminalized, black and favela culture have always been seen as an issue for the police. Even today, there is fear of black culture and of black religiosity. According to Barros, in schools, this manifests itself mainly through evangelical parents: “but obviously it has to be talked about because there is no way to disconnect one thing from the other. Many times, there is religious racism coming from the school itself, where there is rejection, and from guardians, who are inclined towards other religious denominations and don’t want their children to have contact [with African cultures and religions].”

Diniz is evangelical, and often uses her knowledge of her own religion to reason with parents who disagree with the law. “I feel very comfortable discussing this kind of thing. If a guy comes to me complaining: ‘ah, you made a child listen to samba.’ No, hold on! Do you remember that David used to dance? So, this helps me facilitate the dialogue in some way.”

Action Strategies

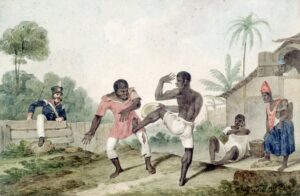

Ronaldo Messias Lacerda has worked as a physical education teacher in Rio’s public school system for over 30 years. As a capoeira master, he says his goal is, “that each school in Rio de Janeiro have a capoeira instructor who will work on cultural aspects along with the educational side.” In these three decades teaching, Mestre Ronaldo (as he is known in capoeira circles) has seen the importance of capoeira in the social, physical, and educational development of his students.

Ronaldo Messias Lacerda has worked as a physical education teacher in Rio’s public school system for over 30 years. As a capoeira master, he says his goal is, “that each school in Rio de Janeiro have a capoeira instructor who will work on cultural aspects along with the educational side.” In these three decades teaching, Mestre Ronaldo (as he is known in capoeira circles) has seen the importance of capoeira in the social, physical, and educational development of his students.

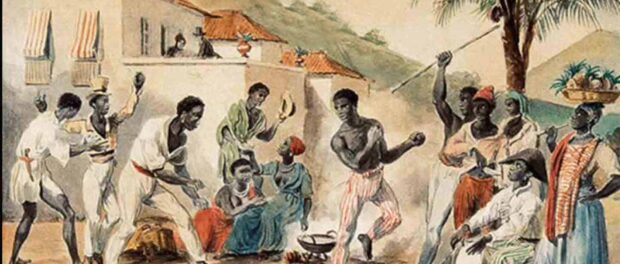

Ronaldo Lacerda currently teaches at three schools, all located in the favela of Rio das Pedras, in the West Zone of Rio. He’s based all his teaching methods in African origins for some time. “Physical education is Eurocentric. I spent three years teaching volleyball, indoor soccer, basketball, and handball. After that, I started to work only with capoeira, maculelê, puxada de rede (miming of pulling in a full fishing net) and samba de roda,” he says.

Even before Law 10,639/03 came into effect, Lacerda was teaching his physical education classes in a way that valued Afro-Brazilian cultural heritage. He explains what changed once the law was approved: “I started to utilize the national legislation. In the beginning, I had some trouble with evangelical mothers. Their pastors would say, ‘you can’t do this, this is macumba (a disparaging term referring to Afro-Brazilian religions)!’ With the introduction of the law, I was able to better discuss this [with students’ families]. Against the weight of the law, the more religious parents had fewer arguments against the teaching plan of physical education classes.”

Even before Law 10,639/03 came into effect, Lacerda was teaching his physical education classes in a way that valued Afro-Brazilian cultural heritage. He explains what changed once the law was approved: “I started to utilize the national legislation. In the beginning, I had some trouble with evangelical mothers. Their pastors would say, ‘you can’t do this, this is macumba (a disparaging term referring to Afro-Brazilian religions)!’ With the introduction of the law, I was able to better discuss this [with students’ families]. Against the weight of the law, the more religious parents had fewer arguments against the teaching plan of physical education classes.”

He manages to incorporate his more democratic vision of teaching well in all the places where he currently works. However, only at one school did he not have to fight for this. When he began working at Cláudio Besserman Vianna Municipal Elementary School, he found an environment where Afro-Brazilian history and culture were already part of the teaching plan. “I was called to this school because of their Africanity; it goes all the way through to the management level. The coordinator, Maria Aparecida, the principal Maria, and another principal named Cátia, are all deeply involved in the community, and work in the tradition of Paulo Freire. So, I already came to this school knowing I could do my work in peace,” says Lacerda.

He manages to incorporate his more democratic vision of teaching well in all the places where he currently works. However, only at one school did he not have to fight for this. When he began working at Cláudio Besserman Vianna Municipal Elementary School, he found an environment where Afro-Brazilian history and culture were already part of the teaching plan. “I was called to this school because of their Africanity; it goes all the way through to the management level. The coordinator, Maria Aparecida, the principal Maria, and another principal named Cátia, are all deeply involved in the community, and work in the tradition of Paulo Freire. So, I already came to this school knowing I could do my work in peace,” says Lacerda.

One of Lacerda’s strategies is to use capoeira songs to talk to students about the enslavement of African people in Brazil. Another didactic tool he uses is, at the beginning of the year, to separate classes into groups of six students, with each group responsible for an African country. Each group has to learn about the dances, educational systems, and languages of the country in question. As a final assignment, Lacerda asks students to make typical dishes from these countries and present the main features of the country they have chosen. “In this way [students] [involve] parents, which is a struggle schools have: to integrate the father and the mother in the educational process. And it’s so cool because sometimes they don’t have an ingredient, but they substitute it. So, they bring in a dish from each country, and at the end of the year we have an exhibit,” says Lacerda.

One of Lacerda’s strategies is to use capoeira songs to talk to students about the enslavement of African people in Brazil. Another didactic tool he uses is, at the beginning of the year, to separate classes into groups of six students, with each group responsible for an African country. Each group has to learn about the dances, educational systems, and languages of the country in question. As a final assignment, Lacerda asks students to make typical dishes from these countries and present the main features of the country they have chosen. “In this way [students] [involve] parents, which is a struggle schools have: to integrate the father and the mother in the educational process. And it’s so cool because sometimes they don’t have an ingredient, but they substitute it. So, they bring in a dish from each country, and at the end of the year we have an exhibit,” says Lacerda.

For Lacerda, it is important that educators not forget how important black people were and are for the growth of Brazil, and how much elements of black culture have built the national identity. “This country grew because of slave labor, so I think it’s important that we not forget that. And whoever can, enjoys and wants to work their lessons based on this, great! I think it is very important for the knowledge of our people.”

Podcast version available in Portuguese onSoundCloud, Spotify, YouTube, and other players.

About the author: Euro Mascarenhas Filho is a journalist and contributor to the Piratininga Communication Center (NPC) news service. He is author of the podcast Antena Aberta.

About the artist: Born and raised in Complexo do Alemão, David Amen is co-founder and communications producer of the Roots in Movement Institute, a journalist, graffiti artist, and illustrator.

This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.