This article, published in Portuguese on Brazil’s Children’s Day, illustrates the effects of racism on the mental health of black children. It is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

I’ve been really sad. I never thought I’d live through a health crisis like the coronavirus pandemic. Everything’s been at a high around here: my feelings, the lack of prospects, unemployment, the price of gas, prices at the supermarket and all of my personal dilemmas. Everything feels raw.

But before being a man, I was a child. A black child. All of my layers and everything I demand of myself today come from that child. Through tales of my own life experiences, I, Cleyton Santanna, a journalist and screenwriter who was born and raised in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense, will bring to light recent data on an issue that is not often discussed: the mental health of black children.

Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, introduced the idea that the most important phase in building our character is early childhood—when all our experiences and various family relations influence our development and shape the adult we will become. That is why the mental health and stimuli provided to children and babies are crucial.

To be a child in the 2000s was to live the promise of a new and more connected world. To be a black Brazilian child at the turn of the millennium was to live under the weight of the responsibility of making this promise of social mobility come true, and to unearth an entire history that’s been stuck in our throats throughout the over 400 years of social injustice which have been the period of slavery and post-slavery in Brazil.

When I was around seven, eight years old, I remember spending entire afternoons in agony, feeling an anguish that was almost too big for my skin. I lived in a very humid house, a home that provided no comfort whatsoever. And, even back then, I’d think to myself, “Man, I need to make something of myself. For these bare walls with no plaster; for this bathroom with no floor tiles and no sink; for this cement-floor kitchen.” The reality of my parents’ house only changed recently. But the way it affected me has stayed to this day. Yes, I was an anxious child, a child with internal demands that no child deserves to make on themselves. Only now do I understand the harm done to my mental health by the racist structure that paved my family’s path since slavery.

The 2017 Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting presented research demonstrating the harmful effects racism can have on a child’s health. The study showed that the combination of factors such as racial discrimination and low income provide for higher rates of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), anxiety and depression in American children.

The 2017 Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting presented research demonstrating the harmful effects racism can have on a child’s health. The study showed that the combination of factors such as racial discrimination and low income provide for higher rates of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), anxiety and depression in American children.

When we are still learning to deal with our feelings during childhood and are also bombarded by the harsh reality of racism, factors such as the troublesome use of addictive substances, the inability to live an independent life, problems with the law, dropping out of school, financial limitations, physical health problems and suicide become more likely challenges in adult life. Many of us don’t know how to overcome these situations. Corroborating with a global alert from the World Health Organization that says that “there is no health without mental health,” a great portion of the black population is ill. In Brazil, in 2019, the Ministry of Health showed that 60% of young people between the ages of 10 and 29 who commit suicide identify themselves as black.

Besides the precarious conditions of my personal life journey, as I’ve mentioned, we are also subjected not only to openly racist attacks, but to a social structure that puts us down, erases us, humiliates us or associates us with all things bad. The first time you see this is in the school environment, where black children can fall victim to stigma and discrimination due to their physical appearance. As a consequence, we internalize there and then negative characteristics that are attributed to a feeling of inferiority, behaviors such as the need for isolation, shyness, aggression and the eternal feeling of not belonging. In my case, school was a peaceful environment, but I know that’s not the reality of most of us, particularly for black girls.

How To Identify These Symptoms in Children?

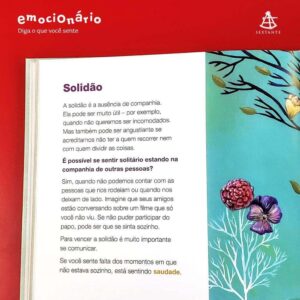

First of all, it’s important to let children know that feelings such as fear, anger, sadness and anguish are inherent to any human being. To do this, there’s a great book called Emotionary: Say What You Feel, written by Cristina Núñez Pereira and Rafael Valcárcel. The authors propose a dialogue with children about the most varied emotions, which ends up being good for adults as well, since many of us don’t know how to embrace our feelings and much less understand that we deserve to have them.

The focus of your attention should be whether or not you feel or notice these emotions in your children more often or more intensely than usual. When I was a kid, for instance, I remember getting that way—anguished—every weekend or when the day was coming to an end. My mom always tried to understand and would tell me to take a shower and relax. I remember that after the shower, I’d hold on to her sitting on the couch and cry a lot. If your child shows symptoms such as gain or loss of appetite, if they have a hard time falling asleep, are always tired or if they stay away from friends and from family, it’s important to see a health professional, a pediatrician or psychologist and to never treat the child’s feelings with disdain. Quite the opposite: this child needs to be heard. Listening is an important way of embracing issues related to physical and emotional wellbeing. All of these efforts echo in the healthier development of children and teenagers and allow them to be happier throughout their life’s journey.

The focus of your attention should be whether or not you feel or notice these emotions in your children more often or more intensely than usual. When I was a kid, for instance, I remember getting that way—anguished—every weekend or when the day was coming to an end. My mom always tried to understand and would tell me to take a shower and relax. I remember that after the shower, I’d hold on to her sitting on the couch and cry a lot. If your child shows symptoms such as gain or loss of appetite, if they have a hard time falling asleep, are always tired or if they stay away from friends and from family, it’s important to see a health professional, a pediatrician or psychologist and to never treat the child’s feelings with disdain. Quite the opposite: this child needs to be heard. Listening is an important way of embracing issues related to physical and emotional wellbeing. All of these efforts echo in the healthier development of children and teenagers and allow them to be happier throughout their life’s journey.

It’s obvious that we cannot look at the issue thinking solely of the challenges we have in dealing with our emotions. Besides the lack of access to knowledge, there is a lack of multi-sectorial public policies that involve families, communities and the health, education, and social welfare systems. Mental health should be in the foreground, since only when it is balanced can we have quality human development.

About the author: Cleyton Santanna hold degrees in journalism and screenwriting from UFRRJ and the CriaAtivo Film School. He uses his YouTube channel to address oddities, ancestry, and Afro-Brazilian culture. In 2017, he produced two documentaries: “Entre Negros” (Between Blacks) and “Tudo Vai Ficar Bem” (Everything is Gonna Be OK), and was recognized as a screenwriter in 2018 by the Creative Economy Network for the short “Vandinho.” He is currently a communicator for The Museum of Tomorrow and hosts the Influência Negra podcast.

About the artist: Illustrator Yara Santos is a student of generalist design at the University of São Paulo (USP). Born and raised in the periphery of São Paulo, she seeks to represent elements of the black and peripheral culture in which she is inserted in her art. Most of her production is centered on digital techniques.

This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.