The Jacarezinho massacre of May 6, the largest ever chronicled in the city of Rio, brought the oversight of police actions back into the public debate and to consideration by State policymakers. Just over three months later, on August 29, State Deputy Carlos Minc wrote on social media: “If the bill had already been passed, there would have been no Jacarezinho massacre. In São Paulo, the installation of these cameras reduced mortality in the actions of the Military Police by 40%.”

Minc was referring to Proposed Bill 265/2015, only approved in May of this year by the Rio de Janeiro Legislative Assembly (ALERJ), six years after it had been introduced. The law’s conception, however, is even older. The Proposed Bill presented in 2015 was an update of Law 5,588/2009—which was not being complied with—drafted by then-State Deputy Gilberto Palmares.

At the time, after being approved by ALERJ, the bill was vetoed by Rio’s then-governor, Sérgio Cabral. In an objectionable manner, and without considering that it is already common practice elsewhere, Cabral deemed the project prejudiced towards the police. At the end of 2009, the governor’s veto was overturned by ALERJ, which approved the project, establishing the installation of video cameras in Military Policy, Civil Police and Fire Department vehicles.

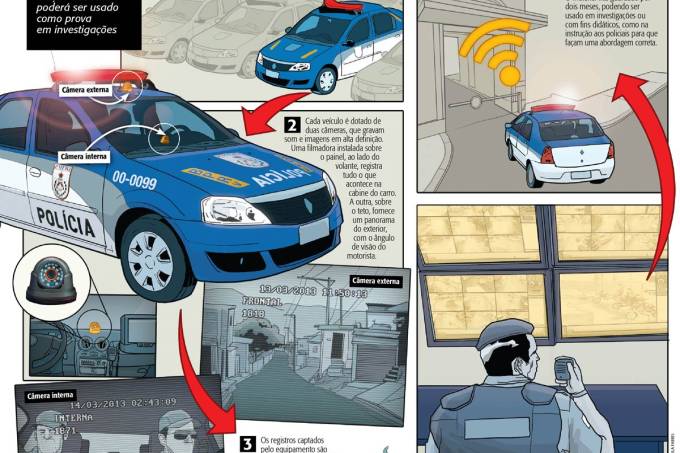

The recording of images and audio would be connected to a central monitoring system, which aimed to protect the population from “bad cops.” At the same time, the system would shield police forces from untrue accusations. The project approved in 2009, however, was never implemented.

The installation of cameras in public security vehicles and on uniforms should provide factual evidence in cases where police officers are involved in illicit and criminal occurrences, whose investigation, without cameras, would only be possible from witness accounts—often nonexistent.

However, in the last decade, much has changed, and today there are new elements that can hinder the effective use of this policy and that, therefore, need consideration.

Today, we have paramilitary militia members holding public office, exercising increased economic and political power, expanding their ground in peripheral regions, and obtaining the support of entrepreneurs and members of the judiciary. When asked about the militia’s expansion—including members of both the Civil and Military Police—and the risk that these organized groups might systematically circumvent the monitoring established by Proposed Bill 265/2015, Carlos Minc replied: “They always try to act in a way that obstructs the production of evidence. We must make it clear… that cameras favor the performance of good professionals,” said the deputy.

Another controversy involved the initial five-year storage period of recorded images—a period considered appropriate by experts to establish complete trial evidence. However, after negotiations between the state assembly and governor, a period of two years was established. Sometime later, following the completion of a technical study, the State Secretariat of Military Police proposed yet another reduction. Due to technological and budgetary constraints, the Secretariat proposed to store the videos for a maximum period of only two months after the recorded event.

“This 60-day period is too brief considering the slow pace of investigations. However, in more serious cases, we had an important victory, and managed to increase the storage period to twelve months,” explained State Deputy Carlos Minc.

For sociologist Adriano de Araújo, executive coordinator of Fórum Grita Baixada, a social movement dedicated to fighting State violence in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region, more transparency is needed in implementing this policy.

“The way this is done—including external control mechanisms—will determine whether or not we will achieve an effective reduction in the lethality of police actions. I do believe, however, that we should neither individualize nor subjectify police or any other State action. We have a structure that is proven to be highly lethal to black, poor and peripheral populations. A whole set of facts make Rio’s police one of the most lethal in Brazil and this needs to be faced by all of us. The use of cameras is important, but it is only one element of this equation,” argues Araújo.

Like Minc, Rodrigo Mondego, vice president of the State Council for Human Rights of the Brazilian Bar Association, Rio de Janeiro Chapter (OAB-RJ), shows enthusiasm and considers legitimate the arguments that a policy related to technological innovations can achieve good results in “cleaning up” public security in the state of Rio.

“Over the years a lot has changed, including the technology used to do this monitoring. There weren’t many smartphones around, for example. The ability to produce images in the area of public security highlighted several cases that were later on investigated and resolved. When the law was implemented, it proved effective in confronting ‘bad’ police officers, especially in the case of Favela da Palmeirinha, where they killed one boy and arrested another, accused of dealing drugs. The camera in the car proved the officer’s allegations were false. A similar case happened in Morro do Sumaré, where the truth came to light thanks to a video,” says Mondego.

He adds: “Unfortunately, due to their modest legal applicability in generating evidence against ‘bad agents,’ the cameras cannot be considered a complete success yet. Today, these cameras are cheaper to install, more effective in terms of storage and the amount of data they can store, so I feel somewhat more hopeful for new results,” Mondego points out.

Despite good intentions, not everyone shares this hope, as evidenced by researcher Pedro Paulo da Silva, from the Center for Studies on Public Security and Citizenship (CESeC). He recalls that, according to data from the Brazilian Public Safety Yearbook, an annual publication prepared by the Brazilian Forum on Public Safety (FBSP), black officers have the highest mortality rate although they are a minority in corporations. White officers, who make up 56.8% of the force, were victims in 34.5% of homicides. Black officers, on the other hand, represent 42% of police ranks, but bear 62.7% of all officers killed.

“The biggest problem with the debate about cameras is that there seems to be an indisputable certainty about the effectiveness of this technology… [there is] a gray area between this technology being ‘good’ or ‘bad.’ When we talk about police victimization, the first issue should always be that most police officers die off-duty, so it would be more useful to investigate the context of these killings and develop strategies to prevent police officers from reacting to robberies in haphazard ways or using weapons in interpersonal conflicts, as well as investigating police officers’ executions in off-duty hours to try to elucidate why this occurs,” said Silva.

In the researcher’s opinion, as public policy and as a contribution to reduce racist actions in police raids, cameras on officers’ uniforms and vehicles fall far short from solving the issue: “It is an uncomfortable assumption that police officers are not intelligent enough to develop new ways of brutalizing the population from within control mechanisms. After all, we’re talking about racism and racism can’t be solved by dealing with its consequences. It will only [be resolved when we address] the racist roots of the police. What guarantee do we have that the video of a person being killed by the police will guarantee there is punishment?” questions Silva.

As an example, the researcher recalls: “We can mention the United States‘ cases, where there have been videos of several people’s deaths and the police were not punished, with the exception of the George Floyd case. And you don’t even have to go that far. Did people forget the video recorded with Claudia’s body being dragged by a police car? Did that video change anything?”

Luciano França, representative of the Rio chapter of the Front for Decarceration, a movement that fights for a decrease in the prison population, mostly made up of black, peripheral and low-income people, also sees the so-called positive results of this policy with great caution.

“This State’s modus operandi regarding surveillance and monitoring is hardly surprising. Our doubt is whether a law of this type will prevent acts of truculence, violence and torture. We do not know if the State will comply with the law that mandates the installation of cameras in all police vehicles. Will this law also be extended to the helicopters and armored cars that invade favelas and are used as killing machines? The State is racist and has no commitment to the lives of black and peripheral populations and this video equipment will not change that,” says the activist.

“The logic is to serve the security market. Reparations will occur the moment we implement public policies aimed at decarceration and demilitarization and when other short, medium and long-term affirmative actions are adopted,” concludes Luciano França.

About the author: Fabio Leon is a journalist, human rights activist, and media advisor for the Fórum Grita Baixada.