This article is the latest contribution to our award-winning reporting project, Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.

We hear about “right” and “left” all the time. Since we were children, we learned that there are different sides and that understanding them is important to the basic tasks of life. During elections here in Brazil, we hear a lot that candidate X or Y is from the Left or from the Right, but few people actually understand what this means. Sometimes it even sounds like a football match or something, right? But it’s much more serious than that!

It is important at least to understand what these terms mean and how they directly affect the lives of Afro-Brazilians and favela residents. More than that, it is necessary to provide an alternative. The purpose of this text is to show that aquilombamento is a way out for the emancipation and autonomy of our people.

There are several ways of looking at the practice of politics. One of the main ones is through economics, a social science that deals with our resources and proposes ways to deal better with them, making the best use of wealth, seeking to multiply it. Economics can be a way of doing politics that takes into consideration that existing resources can promote social well-being or not. But, ultimately, who or what can do that?

There is a political entity responsible for the administration of the country. Sometimes we even confuse it with the country itself, but they are different things. I’m talking about the State, with a capital “S”. This State is also different from the states of the federation, such as Rio de Janeiro, Rondônia, Sergipe and so on.

There are several ideas and ways of administering a State and, in Brazil, those who choose the way to administer it are the people, through direct elections. The diversity of political parties is, in principle, a reflection of the diversity of thoughts and views of the public on how to manage State resources. When the voter chooses party A or B, they are voting not only for a person, but for a form of administration, for a vision on how the State should be organized.

A long time ago, around 1789, in the context of the French Revolution, the French National Constituent Assembly was organized as follows: to the left of the president of the parliament were the Jacobins, people in favor of the revolution, republicans who wanted the dissolution of the monarchy; and to the right were the Girondins, supporters of the installation of a constitutional monarchy in France. These two groups had very different views on how the State should behave in relation to the economy. Time went by, new ideas emerged and adapted to new times and places, so that now we no longer have this 18th century notion as our only reference.

Major events marked and divided the two political spectrums in Brazil and in the world. Some primary ones were the Paris Commune, World War I, the Russian Revolution, Tenentismo, Coluna Prestes, the rise of Nazi-fascism, Integralism, World War II, the Cold War, and anti-colonial struggles in Africa and Asia. New names and parties emerged and succeeded each other within the left and the right wings nationally and internationally during these past two hundred years. Both sides took on very different nuances and trajectories. Today, Left and Right are defined political concepts that vary according to the territory and its local political tradition.

Within each side, there are groups that are very different from each other and sometimes even opposites. When we talk about “American Left” and “European Left” or “liberal left” and “communism” we are referring to completely different things, just as between “liberal right” and “conservative right” or between “neoconservatism” and “fascism.” Some of these groups have in the past declared war on others within their own political spectrum. The diversity is so great that left and right are characterized from their most radical and extremist versions, such as “anarchism” and “libertarianism,” to their variations less demanding of change, the so-called “political center,” the “center-left,” and the “center-right.” Sometimes there is greater similarity between groups from different sides than within each of the sides themselves. Therefore, what we call “Left” and “Right” today is quite different from what emerged from the French National Constituent Assembly.

Very generally speaking, the Left believes that the State should interfere in the economy, maintaining large state structures for the generation of resources and direct investment in public facilities, such as schools, healthcare, security, leisure, and culture. In general, for groups on the Left, ensuring the basics for survival for all is the primary function of the State. Taxes administered by the State are the major source of revenue to guarantee these services.

In contrast, the Right believes that the State should not interfere in the economy in this way. The economy, the large wealth-generating institutions, and many facilities including schools, health clinics, security, leisure and culture should be managed by the private sector to ensure competition, leaving prices to be automatically regulated by the free market. In this perspective, people (seen as “consumers”) pay for the use of private equipment and services, paying minimal taxes to maintain a small State. The profits from the management of these services remain with the entrepreneurs, who allocate resources according to their market strategy and not according to public interest. Just as occurred with the Left, over time a schism has appeared within the Right, encompassing several sub-groups that were quite different from each other, but that still recognize themselves as part of the Right.

I’ve listed some economic characteristics, but I should highlight that there are variations on both sides of the aisle. It should also be understood that both fields have stances that go far beyond the economy. These can be, for example, about social guidelines (sexuality and gender, for example), religion, and forms of government (democracy, dictatorship, aristocracy, monarchy, etc.). Allying yourself with one group or another is ultimately about declaring which one will favor your survival when managing the country’s resources.

And in the Favela, How Is This Reflected?

The story of every favela is the story of the struggle of black people, indigenous people, and other marginalized groups for survival in Brazil. When I talk about survival, I am not just talking about the right to breathe, but the right to exist in an expression of culture and spirituality, with access to health, education, and leisure that respect your ancestral ways of living. In other words, the right to exist.

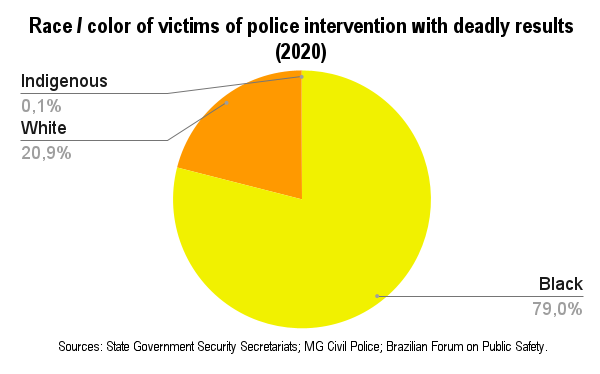

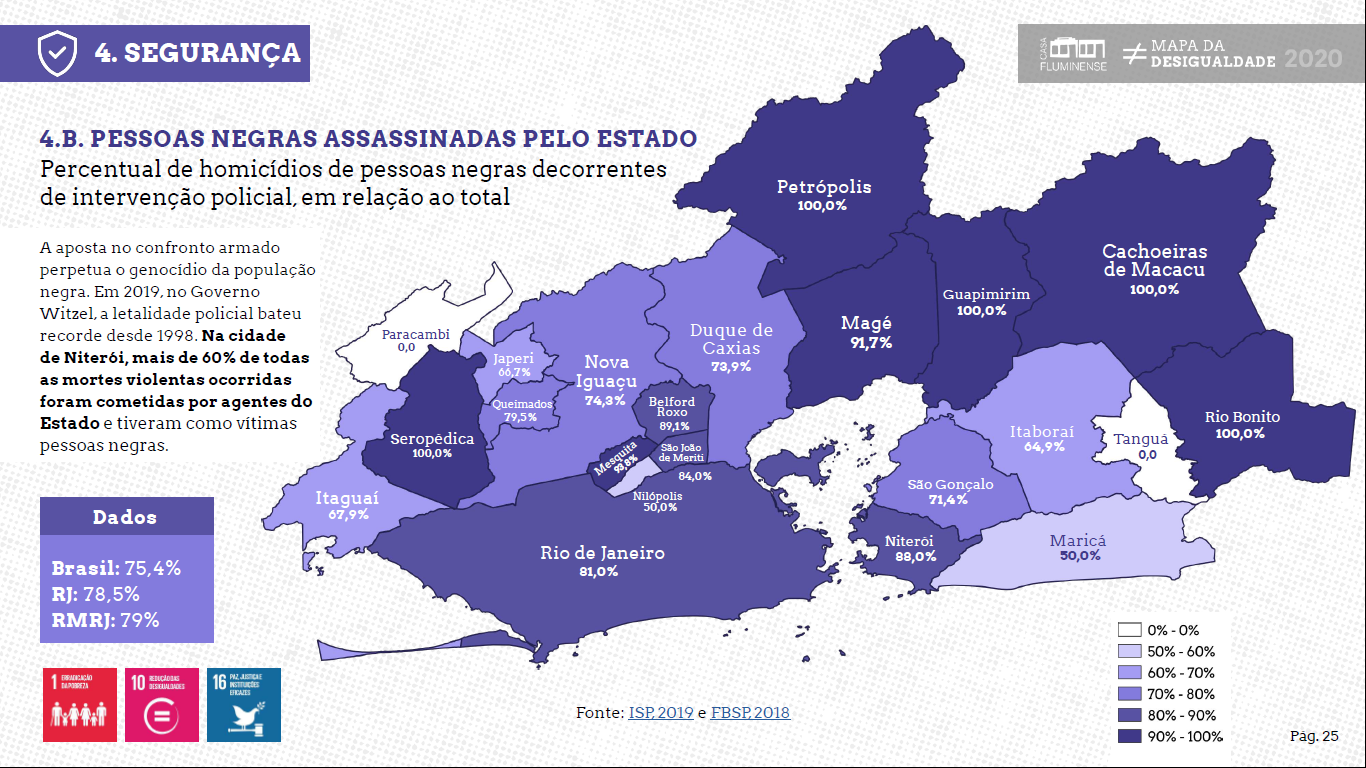

Since the birth of the first favela, today known as Morro da Providência, the Brazilian State has owed a debt to favela residents. Numerous promises for adequate housing have been made historically, all of them insufficient to solve the nation’s housing problem. Along with this, we watch the growing violent onslaught against favelas in a war on black people and on the poor disguised as a war on drugs. The result is the absurd death rate of black people as a result of police operations without any reason to justify so many lost lives.

Often, the media reports an absurd case of violence. The question remains: is it incompetence or is it a project? Some cases become emblematic and remain in our memory. That’s the case of the Special Operations Battalion (BOPE) policeman who mistook a drill for a gun and killed a resident of Morro do Andaraí in 2010. That same year, in Chapéu Mangueira, in the South Zone of Rio de Janeiro, Rodrigo Alexandre da Silva Serrano was hit by three shots fired by police officers from the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) because he was carrying an umbrella. In 2012, in Avaré, a city in the state of São Paulo, a worker was shot and killed by a shot in the neck fired by a São Paulo Military Police corporal, who mistook a Bible in the man’s pocket for a gun. In 2018, a resident of Complexo do Alemão had his crutch mistaken for a gun and was hit in the head by shrapnel. Recently, in 2021, in Favela do Piolho, in São Paulo, residents assert that a teenager was hit in the head by a bullet after having his lunch box mistaken for a gun.

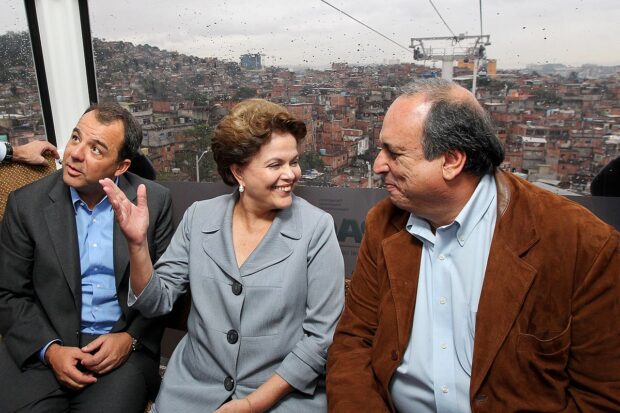

This behavior of the State towards the favela has not been different under any political administration to date, whether on the Right or on the Left. Both have dealt hard blows to favela residents, intensifying their punitive policies and paying little or no attention to integrating these territories with the formal city. An example of this is how electoral alliances were formed to allow the Brazilian Left to come to power. This meant not only a platform that brought together people who were previously political opponents, but also the composition of a legislature, a secretariat, and ministries that had no converging views on how public administration should be.

Government coalitions are what provide elected officials with the power to realize public policies, though sometimes they require supporting policies contrary to the perspectives of one’s own constituents who originally elected and supported the candidate in power. An example of public policy carried out by right-wing governments and supported by the Left, in a coalition government, that has a direct impact on the livelihoods of favelas is the failure of the Pacifying Police Units project. Adopted as a security policy during the administration of Governor Sérgio Cabral (PMDB Party of Rio de Janeiro), the UPPs were supported by many on the Left with the argument that they would be a solution to the problem of violence and drug trafficking. For the Left, the success of this policy would come mainly through its social component, UPP Social, which promised the installation of cultural facilities and social intervention in the territories where police units were established. But like its military twin, UPP Social did not have satisfactory results, bringing frustration and intensifying the feeling of abandonment of our people.

Government coalitions are what provide elected officials with the power to realize public policies, though sometimes they require supporting policies contrary to the perspectives of one’s own constituents who originally elected and supported the candidate in power. An example of public policy carried out by right-wing governments and supported by the Left, in a coalition government, that has a direct impact on the livelihoods of favelas is the failure of the Pacifying Police Units project. Adopted as a security policy during the administration of Governor Sérgio Cabral (PMDB Party of Rio de Janeiro), the UPPs were supported by many on the Left with the argument that they would be a solution to the problem of violence and drug trafficking. For the Left, the success of this policy would come mainly through its social component, UPP Social, which promised the installation of cultural facilities and social intervention in the territories where police units were established. But like its military twin, UPP Social did not have satisfactory results, bringing frustration and intensifying the feeling of abandonment of our people.

The Right does not have a project for favelas and has been reinforcing stereotypes and an approach where problems are not faced at their source, but rather, the blame falls on the people, favela residents, ignoring the historical processes that brought us to this point. An example is the insistence on the discourse of meritocracy and support for efforts such as lowering the legal age of criminal responsibility that directly affect black and favela youth.

Under right-wing governments such as those of former Governor Wilson Witzel (PSC Party) and current Governor Cláudio Castro (PSC Party) in Rio de Janeiro, or President Jair Bolsonaro (PL Party) at the national level, the undeniable relationship between political right and necropolitics has been made obvious. Witzel, for example, on campaign, said that favelas should be bombed. After being elected, he spent public money riding a helicopter and landing on the Rio-Niterói Bridge just to commemorate with theatrical excitement the death of a person who had hijacked a bus. After Witzel’s impeachment, under Castro’s government, the rhetoric of unrestricted support for the police and for human rights violations provoked the biggest police massacre in the history of Rio de Janeiro: the Jacarezinho massacre, with 29 people murdered in the Jacarezinho favela last May. Cláudio Castro even went public after the massacre to defend police action in Jacarezinho.

Under right-wing governments such as those of former Governor Wilson Witzel (PSC Party) and current Governor Cláudio Castro (PSC Party) in Rio de Janeiro, or President Jair Bolsonaro (PL Party) at the national level, the undeniable relationship between political right and necropolitics has been made obvious. Witzel, for example, on campaign, said that favelas should be bombed. After being elected, he spent public money riding a helicopter and landing on the Rio-Niterói Bridge just to commemorate with theatrical excitement the death of a person who had hijacked a bus. After Witzel’s impeachment, under Castro’s government, the rhetoric of unrestricted support for the police and for human rights violations provoked the biggest police massacre in the history of Rio de Janeiro: the Jacarezinho massacre, with 29 people murdered in the Jacarezinho favela last May. Cláudio Castro even went public after the massacre to defend police action in Jacarezinho.

Under a far-right government, Jair Bolsonaro and his Minister of Justice, Sérgio Moro, proposed immunity for crimes committed by police officers in action, which would legalize all crimes by Brazilian police. In addition, like much of the contemporary Brazilian right-wing, Bolsonaro promotes a belief that killing is the solution to public security problems. The right believes these problems are favelas’, not of society as a whole. Still campaigning, in 2018, Bolsonaro said that, if elected, he would have Rocinha machine-gunned. He said this to an audience of businessmen during the electoral process. This rhetoric that criminalizes the favela and all this discourse of necropolitics have been central to the Brazilian conservative right in recent years.

In the eyes of the State, in the capitalist regime, whether in an administration of the Right or of the Left, the favela continues to be a repository of cheap labor to move the surplus value and profit machine of Capital. It is with residents of these territories that businessmen use the classic blackmail to keep wages low: “If you don’t want it, I’ll fire you and hire two people for half of your salary.”

In the eyes of the State, in the capitalist regime, whether in an administration of the Right or of the Left, the favela continues to be a repository of cheap labor to move the surplus value and profit machine of Capital. It is with residents of these territories that businessmen use the classic blackmail to keep wages low: “If you don’t want it, I’ll fire you and hire two people for half of your salary.”

Favelas were once important places for the formation of left-wing parties in Brazil. An example of this is Jacarezinho, that once housed offices of parties such as the PT and PDT, but that nowadays suffers from the exodus of its militants, co-opted by academia, as claimed by activist and longtime Jacarezinho resident, Rumba Gabriel.

What we witness today is the occupation of the Right in the favelas via evangelical churches, where liberalism and neo-pentecostalism came together as faith and political practice in favor of the oppression of diversity. Churches clearly have the function of being the ideological basis of the Brazilian Right, including establishing moral guidelines around customs and practices of a personal nature to each citizen, such as who you marry or what you do with your body, which in turn reinforces the dominant faith in these spaces.

What we witness today is the occupation of the Right in the favelas via evangelical churches, where liberalism and neo-pentecostalism came together as faith and political practice in favor of the oppression of diversity. Churches clearly have the function of being the ideological basis of the Brazilian Right, including establishing moral guidelines around customs and practices of a personal nature to each citizen, such as who you marry or what you do with your body, which in turn reinforces the dominant faith in these spaces.

When the focus of transformation leaves the hands of the people and passes into the hands of spiritual beings, the tendency is to naturalize inequalities, criminalize differences, and impose beliefs that the solution comes from the heavens and that, for this reason, we need to mix the state structure with the ecclesiastical structure of certain groups. In this case, the economic and political debate of institutions and organizations shift to the background, since the focus becomes the will of a spiritual being, in which only some believe, but which all are obliged to follow. Thus, values such as participation, accountability, and propositive proposals on issues of public interest lose strength in favor of faith.

Conclusion: Aquilombamento Is the Way Out!

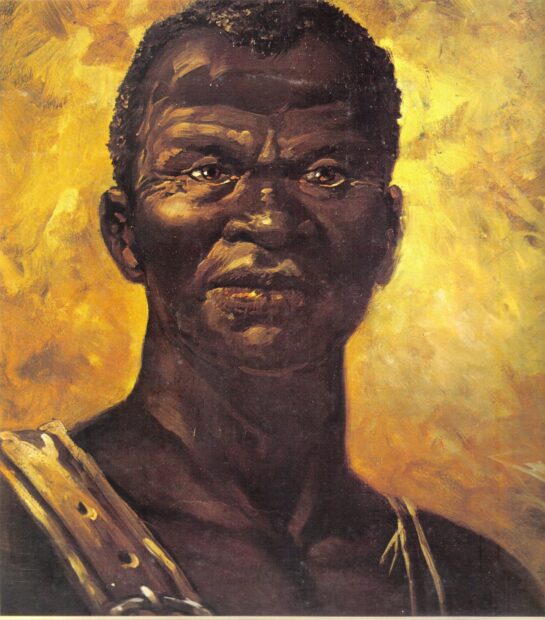

This unfortunate crossroads is not new for our people, but aquilombamento presents itself as an efficient form of favela organization. To aquilombar means treating the favela as what it never ceased to be: a quilombo! The quilombo was the space where enslaved people resisted the system, and, fleeing the spaces of exploitation, got together and created ways of resistance in culture, music, spirituality, and material production. The most famous was Palmares Quilombo under the leadership of Zumbi. In these quilombos, the protagonism was black, although indigenous and white people also found shelter there.

This unfortunate crossroads is not new for our people, but aquilombamento presents itself as an efficient form of favela organization. To aquilombar means treating the favela as what it never ceased to be: a quilombo! The quilombo was the space where enslaved people resisted the system, and, fleeing the spaces of exploitation, got together and created ways of resistance in culture, music, spirituality, and material production. The most famous was Palmares Quilombo under the leadership of Zumbi. In these quilombos, the protagonism was black, although indigenous and white people also found shelter there.

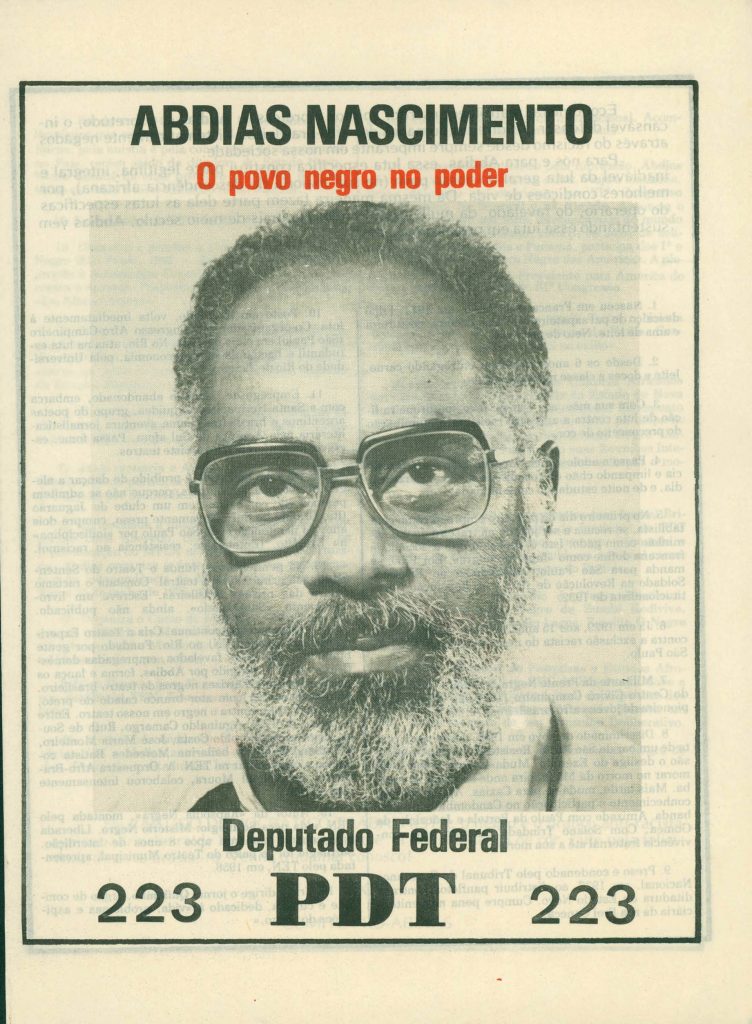

Andrelino Campos in his thesis Urban Planning and the “Invisibility” of Afro-Descendants: Ethnic-Racial Discrimination, State Intervention and Socio-Spatial Segregation in the City of Rio de Janeiro shows how today’s favelas are yesterday’s quilombos. The aquilombamento strategy—also brought up by Abdias do Nascimento, in his book O Quilombismo: Documentos de uma Milunidade Pan-Africanista—is necessary to build a different view of ourselves and understand that we are not a problem for society. On the contrary, if favelas don’t move, the city as a whole grinds to a halt. To aquilombar oneself is to recognize the diversity that exists in our places and make this a point in our favor. This strategy requires positioning. As the philosopher Katiúscia Ribeiro once said:

“No one is half a people.”

In this way, we, black people who have aquilombado, may have different religions, life perspectives, sexual orientations, genders, ethnicities and origins, ideological and party affiliations. However, we will think collectively, very honestly and pragmatically: in order to create conditions for mobilization and social movement, for ensuring survival and fulfilling potentialities, is there more space for us, for the favela, on the Right or on the Left? This question is honest and must be pondered on a personal basis, but it must also be taken to the quilombo at all times, to be discussed collectively. We may not be able to ignore this polarization between Right and Left, but we need to deal with it strategically. All parties have their electoral programs and objectives to be achieved. Let us also have our own and, when dealing with these parties, let us be firm and strategic, pushing them to adhere to whatever is necessary for the emancipation and autonomy of our people. Let’s not be naive, our lives and the lives of ours depend on it! Before choosing Left or Right, we must stand alive and united!

In this way, we, black people who have aquilombado, may have different religions, life perspectives, sexual orientations, genders, ethnicities and origins, ideological and party affiliations. However, we will think collectively, very honestly and pragmatically: in order to create conditions for mobilization and social movement, for ensuring survival and fulfilling potentialities, is there more space for us, for the favela, on the Right or on the Left? This question is honest and must be pondered on a personal basis, but it must also be taken to the quilombo at all times, to be discussed collectively. We may not be able to ignore this polarization between Right and Left, but we need to deal with it strategically. All parties have their electoral programs and objectives to be achieved. Let us also have our own and, when dealing with these parties, let us be firm and strategic, pushing them to adhere to whatever is necessary for the emancipation and autonomy of our people. Let’s not be naive, our lives and the lives of ours depend on it! Before choosing Left or Right, we must stand alive and united!

Listen to the Accompanying Podcast in Portuguese Here:

About the author: Jeferson Rodrigues is 34 years old from Complexo do Alemão. He graduated as a teacher in geography at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) and is a specialist in Public Administration at CEPERJ. He uses social media to talk about race and spirituality. He maintains the Dide YouTube channel where he speaks on racial issues among members of Afro-Brazilian religions.

About the artist: Lorena Portela is an artist, environmental engineer and doctoral student in public health (ENSP/FIOCRUZ). Her research in the field of health and the visual arts dialogues with socio-environmental issues and the affirmation of agroecology as a practice of emancipation.

This article is the latest contribution to our award-winning reporting project, Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.