This article is the latest contribution to our award-winning reporting project, Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro. It is also part of a series created in partnership with the Center for Critical Studies in Language, Education, and Society (NECLES), at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), to produce articles to be used as teaching materials in Niterói public schools.

This story describes a process of intergenerational and interracial coeducation in Brazil, the starting point of which was a set of questions asked by my mother, Andréa Luisa. She is a 54-year-old white, heterosexual, cisgender woman. Her questions were directed at me, a 31-year-old black, gay, cisgender male. Some of these inquiries could have a broader educational impact if shared.

“You talk about the struggle of black people, but where do I, who have always been discriminated against for being from a favela, come in? I, who had to carry your birth certificate in my purse because people didn’t believe I was your [biological] mother?”

Snippets like these started to catch my attention from the other end of the phone. I, who in addition to being her son, became a teacher and social scientist thanks to her efforts, shuddered with each question and with the possibility of more complex questions. So I accepted the challenge of researching and studying that which I had no idea how to respond to. I wanted to build more democratic and anti-racist exchanges with my loved ones. Prior to that, I did not seek general explanations for the questions of my and of many other family configurations existing in our country, composed of the diaspora and of forced miscegenation.

Considered the first space for socialization, the family is, in general, made up of groups of people who are generationally distinct, who exchange and share experiences and knowledge. Commonly involved in situations of conflict, negotiation, cooperation, transmission of values, emotional demands and expectations of reciprocity, we have the chance to learn every day while also teaching. These processes of learning through teaching and teaching through learning that we share within a family are known as coeducation. The first steps we take in the world are designed based on the members of each kinship model and our family configuration.

Considered the first space for socialization, the family is, in general, made up of groups of people who are generationally distinct, who exchange and share experiences and knowledge. Commonly involved in situations of conflict, negotiation, cooperation, transmission of values, emotional demands and expectations of reciprocity, we have the chance to learn every day while also teaching. These processes of learning through teaching and teaching through learning that we share within a family are known as coeducation. The first steps we take in the world are designed based on the members of each kinship model and our family configuration.

The experiences and access to the universe of language occur initially within these family relationships. We educate each other in a context of both permanence and changes in conceptions, values and practices taken on by each member. The importance of the intergenerational nature of family is usually highlighted when we notice glimpses of the worldviews of the elders in the discourses of the younger generations, and vice versa, with diverging and converging trajectories. The family is, fortunately, a place of exchange where everyone learns from everyone else, in community.

Memories that Tug Out Other Memories and Coeducate Us

In 1957, my maternal grandmother, Maria de Lourdes da Silva, migrated from the state of Paraíba to Rio de Janeiro in search of work. Her identity document points to August 24, 1932 as her date of birth, in João Pessoa, but her telling is that this was the year of her registration at a notary, carried out by her father when she was already two years old.

Born into a Christian family, she attended mass at the Catholic Church with her parents, Antônio Silvano and Francisca Miguel da Silva, both white. But grandma also talks about belonging to Catimbó, a magical-medicinal ritual of indigenous origin centered on the cult of herbs, such as the Jurema (mimosa hostilis), a native bush of the wild, and Caatinga, whose bark is used in baths, infusions, smoking and ingestion in healing ceremonies and guidance with discarnate beings. My great-grandmother, Francisca, who was also a rezadeira and benzedeira, something like a blesser and healer, gave birth to eight children, but only six of my grandmother Maria de Lourdes’ siblings made it. As an adult, my grandmother migrated to Rio de Janeiro at the invitation of one of her older sisters who had moved there earlier with her husband.

My maternal grandfather, Luiz Delfino da Silva, left Paraíba to work as a foreman in Rio de Janeiro. The absence of images of me next to him follows a common tale for families without resources to pay for portraits. When the camera arrived, film rolls accumulated waiting to be developed and ended up spoiling. The physical distance came later, with my moving with my parents, older brother and our dog to the state of Espírito Santo, making it impossible to contrast memory with images printed on photographic paper.

I have few oral records of my grandfather’s life trajectory. I know, albeit in a very fragmented way, about him belonging to [the Afro-Brazilian religious tradition of] Candomblé, about his religious position as a pai de santo, as male priests of Afro-Brazilian religions are known, and about his presence in terreiros and houses of worship for most of his life. Family accounts also show how often my grandmother and uncle went to terreiros in Rio’s South Zone taken by him, as well as his wish to initiate my mother into this magical-religious universe of Afro-Brazilian origin. However, one afternoon on the way to mass at a Catholic Church in Copacabana, after leaving one of the apartments where she worked as a maid in Leblon, my grandmother Maria de Lourdes was approached by an evangelist from the Assembly of God Church.

My grandmother’s process of reconversion to Protestant Christianity started a real spiritual battle within the family. When my mother was born in 1967, in terms of religious clashes, “the circus was already set:” my grandmother practiced her faith in the Assembly of God and my grandfather in Candomblé. Raised at the crossroads between the material world and the spiritual world, marked by conversion processes and complex passages, my mother is the main guardian of our family’s narratives.

Mom says that she lived with my grandparents, first, in Baixa do Sapateiro, which is part of Complexo da Maré, in a house on stilts, until they managed to buy the small plot of land where the family built their house, on Travessa da Viçosa, in Morro do Sereno, both of these, favelas in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone. My grandmother lived in this house in Sereno until she needed care and moved into my parents’ house in 2019. My grandfather, after he separated from my grandmother, moved and lived for years in Favela do Pereirão, in the South Zone, with his second wife.

For me, as a child, Rua Pereira da Silva seemed to have no end. It felt like taking a trip. Everything was fascinating: the old buildings, the cobblestone streets, the many trees. The deeper you went down the street, the more similar the landscape was to the one on the way to my grandmother’s house. The entrance to the favela, the aesthetics and precariousness of Morro do Pereirão seemed the same as in Morro do Sereno, in Complexo da Penha. The stairs, alleys and narrow streets were a childhood adventure, a period when everything seems to be created through the force of imagination. I used to lay on my grandfather’s bed, one eye on the cartoon playing on TV and the other on the window where you could admire Christ the Redeemer. That was the view from the South Zone favela. From the North Zone one, you could see the Basilica of Our Lady of Penha atop a cliff, in addition to the planes cutting through the sky near Galeão Airport, on Ilha do Governador.

Always in transit, I grew up taking the 497 bus route, discontinued in 2016. Going from Penha Circular to Cosme Velho, this bus connected the two favelas of my childhood. The trip to Laranjeiras was followed by a whole journey on foot, along the asphalt of Rua Pereira da Silva, and then up the stairs and through alleys and narrow streets to my grandfather’s house, which appeared among the clouds.

Despite being read as white, my maternal family has characteristics that I attribute to caboclos, although they do not remember relatives that would allow them to retrace their indigenous heritage, expressed not only in phenotypic characteristics, but also in social practices transmitted in a naturalized way to each new generation. This perception of a kind of second-rate whiteness is present in my grandmother. She, for example, refuses to be photographed on the grounds that she considers herself ugly. When asked why she thinks she is ugly, the first characteristic she points out is her “yellowish, grimy and stained” skin.

My grandfather, in turn, is described as having “burned” or “spotted” skin due to intense exposure to the sun from working on construction sites. His rough and callused hands didn’t tell me verbally and in detail the stories that I would now like to know about the man with deep blue eyes. Moments when Seu Luiz, on his way to the bus stop with us, made Rua Pereira da Silva seem magical and huge, especially when he raised one of his arms and pointed diagonally and upwards: “That building over there, I built from the ground up!” he’d show us proudly .

A seamstress who made her own clothes, my grandmother entered school when she was 6 years old, but did not attend for more than six months. She learned to read, although she was asked to withdraw and forced to interrupt her literacy process because she did not have closed shoes to attend classes.

The matriarch of this side of my family, she always showed pride in being a great seamstress, being self-taught, a swimmer and cook. One afternoon I asked her: “Who taught you to sew, grandma?” She replied: “I did!” In silence, I’d listen to her talk, recording each new piece of information in my memory. After all, I was taught to listen and not interrupt my elders. As an adult, when I visited her in her little house on Morro do Sereno, I would sit in one of the two rosewood armchairs that she used to put together to serve as a crib when I was little. There, I’d listen to my grandmother recall my drawings and how she thought I was going to become a clothing designer someday. According to her, I’d “make wedding gowns on paper and give them to [her] for safekeeping.” Under her round table, there were many times when childhood was imagined, created and lived.

My grandfather had untrained and firm handwriting. He always asked my only brother, four years older than me, our mother or father, to read labels and documents; or, still, to explain and write down important data in his little notebook.

My mother, in turn, learned the alphabet and basic arithmetic from Dona Doca, a next-door neighbor in Morro do Sereno. She entered school and studied until the age of 14, leaving after repeating fifth grade. The decision was driven by shame and embarrassment caused by a teacher and by her work routine. At the age of 10, she started taking care of the young daughters of her mother’s employers. At the age of 11, she was already sweeping and dusting things. She skipped classes weekly and didn’t stop working until she was 16. The interruptions in school attendance to go with my grandmother to do housework, added to learning difficulties and the excessive impositions of teachers, contributed to my mother, like my grandmother, not finishing her formal studies.

My mother, in turn, learned the alphabet and basic arithmetic from Dona Doca, a next-door neighbor in Morro do Sereno. She entered school and studied until the age of 14, leaving after repeating fifth grade. The decision was driven by shame and embarrassment caused by a teacher and by her work routine. At the age of 10, she started taking care of the young daughters of her mother’s employers. At the age of 11, she was already sweeping and dusting things. She skipped classes weekly and didn’t stop working until she was 16. The interruptions in school attendance to go with my grandmother to do housework, added to learning difficulties and the excessive impositions of teachers, contributed to my mother, like my grandmother, not finishing her formal studies.

“On Tuesdays I would go to my ‘godmother’s’ house, where I was allowed to watch a little TV,” my mother tells me, explaining that it was there that she learned to enjoy soap operas and movies, in addition to reading newspapers, magazines and comic books that she’d find in the trash of her mother’s—my grandmother’s—employers.

Andrea Luisa, my mother, unlike my grandmother, developed a real fascination with photographs. When she married my father, Joás, she got a camera as a wedding gift, which allowed us numerous records of our family nucleus.

Stories in Books and Stories of a Multiracial Family

In mid-2017, when I visited my parents, who were still living in Espírito Santo, I did what I always do when I get home: I took my books out of my bag and spread them out on the living room table. I was surprised by my mother’s question about one of the titles: “What is this book about?” Her attention was caught by Três Famílias: Identidades e Trajetórias Transgeracionais nas Classes Populares (in English, something like Three Families: Transgenerational Identities and Trajectories in the Popular Classes), by anthropologists Luiz Fernando Dias Duarte and Edilaine Campos Gomes. The book is a study on the social dynamics of three Greater Rio low-income family networks. “It’s the work of the researcher who was one of my master’s examiners,” I commented. “Hmm, your teacher, you mean? The one in the picture?” she asked as she leafed through the book and I nodded my head in agreement.

Days went by and, one morning, I woke up and saw my mother sitting on the living room sofa holding the book. “Oh boy, I had terrible insomnia!” she explained, before she continued: “I came to the living room, saw your book and started reading. It’s great, isn’t it?! Very good book! Have you read it?” This time, my answer was no. “I found this one just now at a stall at the Cinelândia Book Fair, on my way here,” I explained. The interest of my mother, a non-anthropologist, in an anthropology text increased my curiosity for her interpretations.

“Oh, your grandmother would like it too, because they talk about the streets where she used to walk and sometimes took me along,” she recalled. From that point on, narratives about us started coming out, stories that I, until then, had never heard. While I make no judgment about anyone’s reading habits, the small library in my parents’ living room is strictly composed of evangelical books belonging to my father. Joas Araujo da Silva is a black, heterosexual and cisgender man, born in Jacarepaguá, in 1964. At the age of 16, he became an evangelical pastor and a neo-Pentecostal missionary, dedicating 42 of his 58 years of life to this vocation.

“Oh, your grandmother would like it too, because they talk about the streets where she used to walk and sometimes took me along,” she recalled. From that point on, narratives about us started coming out, stories that I, until then, had never heard. While I make no judgment about anyone’s reading habits, the small library in my parents’ living room is strictly composed of evangelical books belonging to my father. Joas Araujo da Silva is a black, heterosexual and cisgender man, born in Jacarepaguá, in 1964. At the age of 16, he became an evangelical pastor and a neo-Pentecostal missionary, dedicating 42 of his 58 years of life to this vocation.

The recomposition of my paternal family’s trajectory goes back to my great-grandparents Ovídio Correia da Silva, a traveling salesman, and Antonia da Silva, described by my mother as “a tall, thin, black woman with blue eyes.” One of my aunts on my father’s side says that they were introduced to the gospel and taught to read and write by missionaries from the Baptist Church in Eden (Itinga), in São João de Meriti. The main intention was that they have autonomy in their relationship with biblical scriptures. Although Ovídio did not actually convert, my great-grandmother did, and took their family to the Protestant religion.

My paternal grandfather, Jorge Correia da Silva, was born in the 1930s in Rio de Janeiro. He started working as a shoemaker as a child and was a bus conductor as a teenager. When he reached the age of enlisting, he joined the army and only left retired. My paternal grandmother, Maria Araujo Correia, was born the same year, 1934. She worked in the fields or as a laundress since she was a child; later, she became a reseller of magazine products. Upon marrying, Maria and Jorge took up residence in military villages in the North and West Zones of Rio.

Once, on the phone, grandma told me that she managed to buy the land where she built her house—which populates my family experiences—after working as an orange harvester in the rural area of Baixada Fluminense. My grandparents live on this land in Vila Operária, in Nova Iguaçu, to this day. My parents built the house where they went to live after getting married in this same space, just like other uncles and aunts did. Including my father, my grandparents had four sons and three daughters, all black, heterosexual and cisgender, like them, and with different levels of education. The men work as a mechanic, gunsmith/security, supermarket manager and—my father—evangelical pastor. The women, in addition to being housewives, also work as janitors, hairdressers/seamstresses and caregivers.

“I know even more about your father’s family than my own,” says my mother, between chapters of my anthropology book. In the following weeks, at times, mom would stop reading and make me stop what I was doing to comment on some passage, stressing that my grandmother would also love the book. Sometimes, she’d say that some of the places described in the work were no longer, or still were, as described. It was like diving into her memories of being a carioca from a suburban favela. She even laughed at times. “When are you leaving, again?” she asked. “It’s just that I need to know the end of the story,” she’d say, as my departure approached. When I mentioned the possibility of leaving the book with her, she replied, “I think I’ll have enough time then. It’s just that I’m holding back so I don’t go right to the end of the book and end up missing the plot of all the families in this novel!” In the end, her reading strategies turned out to be much more interesting than mine.

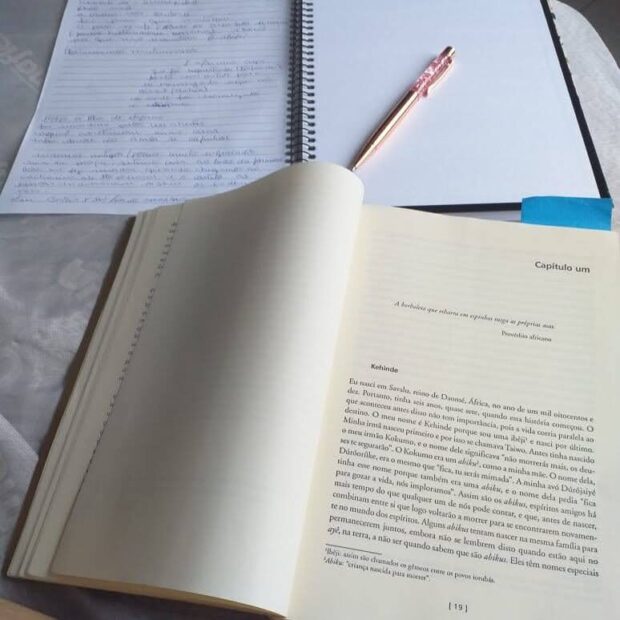

I recently proposed a new reading, this time together with my mother. The proposed novel is called A Color Defect, by black Brazilian writer Ana Maria Gonçalves. Centered on the life of Kehinde, a blind octogenarian woman, she retells her life to her goddaughter so that her story, once written, can be read by the son she had when she was young and who was sold by his own father to pay off gambling debts. Kidnapped and enslaved at the age of 6 from Dahomey, West Africa, she was trafficked to Brazil in the 19th century. Her struggles and conquest of freedom are the backdrop for the story. Likewise, they contribute to establish other voices and narrative possibilities for the historical gaps produced by the erasure and silencing caused by the slavery regime.

I lent my copy to my mother, along with the challenge of carrying out a commented and shared reading. The voluminous 952-page book, divided into ten chapters, was not received with awe by her. On the contrary, the challenge of facing the reading as research, aided by notes and consultation with her teacher son, was accepted. With this co-reading, we have been deepening and producing new and unusual links. I have considered this process of co-reading with my mother as a broad exercise in intergenerational and racial co-education, where orality and writing mix together, furthermore triggered by photographic memories.

I lent my copy to my mother, along with the challenge of carrying out a commented and shared reading. The voluminous 952-page book, divided into ten chapters, was not received with awe by her. On the contrary, the challenge of facing the reading as research, aided by notes and consultation with her teacher son, was accepted. With this co-reading, we have been deepening and producing new and unusual links. I have considered this process of co-reading with my mother as a broad exercise in intergenerational and racial co-education, where orality and writing mix together, furthermore triggered by photographic memories.

“What is this about Africans being Muslims, as described in this book?” “The Malês were important, right?!” “There’s race and ethnicity, is that it?” I started to get these comments and questions through WhatsApp, on a daily basis, and to shudder in terror at the possibility of not being able to learn to teach. But there’s also the excitement and new motivations for challenges mediated by more studies and readings.

Fortunately, my conversations with my mother do not allow me to forget that we need to admit everything that we do not know, in addition to our constant learning processes. In other words: nobody knows everything, whether or not they have degrees acquired through formal education—for example, in my case, as a doctoral candidate and in my brother’s having become a lawyer. Family teaches as much as academic texts or hours spent in university chairs. We need to learn to ask questions without being so fearful of making mistakes. And, above all, we must avoid silencing those who fear being discriminated against when they ask out of lack of knowledge or formal study. Sometimes, the absence of titles and diplomas are understood as synonymous with lack of knowledge, knowledge that is crucial for possible and desirable exchanges between interracial generations, as in the case of my family.

I have learned how much our favela memories can serve as a substrate for the construction of new shared readings about the world. And that there is room in the family for the dismantling of systemic and intersectional oppressions such as racism and classism, as well as misogyny and machismo.

The family, which is primarily an environment for exchanges, is an ideal place to stimulate anti-racist educational activities, especially in families like mine, composed of white and black people, from the favela and from the Baixada, with rising levels of education—unfortunately, still slow and gradual. Personally and as a professional, I bet on the necessary intimacy with reading, which in my case I first acquired from my mother. Her habit and pleasure, acquired from a young age, is maintained by the daily study of the Bible or from the books spread by her youngest son on her living room table.

About the author: Nathanael Araujo is a social scientist and doctoral candidate in social anthropology at the State University of Campinas (Unicamp). A researcher at the Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning (Cebrap), he teaches at the Parque Lage School of Visual Arts and at the São Paulo School of Sociology and Politics Foundation (FESPSP).

About the artist: Natalia de Souza Flores was born and raised in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone and is a member of Brabas Crew. With a degree in Graphic Design from Unigranrio in 2017, she has worked as a designer since 2015. She launched a magazine of collective comics called ‘Tá no Gibi’ in 2017 at the Rio Book Biennial. Her main themes are based in African culture, using cyberpunk, wicca and indigenous elements.

This article is the latest contribution to our award-winning reporting project, Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.