This is the fourth article in a series of four on Brazil’s Black Coalition for Rights and is also the latest contribution to our award-winning reporting project, Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.

Plurality of Voices and Trajectories

Unreflected in our power structures and political representation, the majority—52%—of Brazilians are female. Combining race and gender, black women make up about 28% of the nation, which makes black women our largest demographic. Women head almost half of Brazilian households. Of the families headed by black women, 63% are below the poverty line, while only 39% of those headed by white women are in poverty. Black women are also those who suffer most with unemployment. According to data from Data Labe, black women had double the rate of unemployment of white men in the first trimester of 2021. Moreover, black women receive lower wages than white men and women, and black men. The scenario is so dramatic that a study from the Insper Learning Institution showed that black women with the same educational attainment and graduating from the same educational institutions as white men receive 159% less than they do.

Despite making up the largest demographic, black women in Brazil also suffer from the lowest political representation. The masses, favelas, and peripheries have a color and gender, as do unemployment, State negligence, genocide and famine. The political framework of black women in Brazil is that of an underrepresented majority, but despite this, many of them are on the frontline of the struggle for rights, at the forefront of changes.

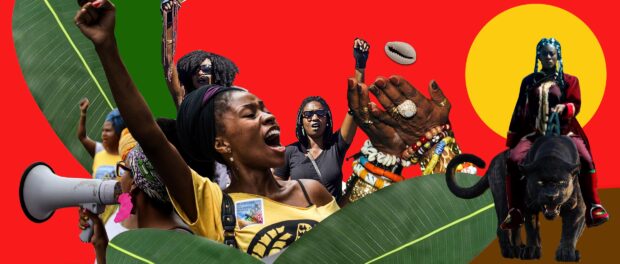

The Black Coalition for Rights emerges precisely from the struggle of black women and men for the right to live. Brought together in coalition, activists of hundreds of organizations from the Brazilian Black Movement, professionals from the most diverse areas including health, education, domestic workers, the construction industry, the samba community, youth from the slam and funk movements, informal and gig workers, favela activists, Afro-Brazilian religious leaders like babalorixás and ialorixaás, priests and pastors, as well as quilombola, ribeirinha, farming, fishing, and LGBTQIA+ populations aim to aquilombar, rooting Brazilian policies in the anti-racist struggle for rights.

To portray this plurality, RioOnWatch interviewed nine voices from the Black Coalition for Rights, with the objective of charting this tree of representation, representativeness and temporalities of the organized Black Movement’s history. Some of these voices have been published in previous texts of the series. In this final article, RioOnWatch introduces three more interviewees, to whom we asked: “What is your voice within the Black Coalition for Rights?”

In these testimonies, Monica Oliveira, Sandra Maria Andrade, and Maria José Menezes give a summary of the country’s structural racism, which led to the consolidation of the Coalition, and of how their voices unite past and present in the construction of a just and democratic future for Afro-Brazilians.

“My Voice is the Voice of Over 6 Million Quilombolas”

A quilombola from the Carrapatos da Tabatinga Community, in the state of Minas Gerais, Sandra Maria da Silva Andrade has over 20 years’ experience as a quilombo activist. She is one of the most active leaders in the state and a founder of the Federation of Quilombola Communities of Minas Gerais (N’Golo). She is currently the executive coordinator of the National Coordination for the Articulation of Rural Black Quilombo Communities (CONAQ). A child of Yoruba deity Xangô, Andrade is the daughter of Dona Sebastiana Geralda, the renowned Mother Tiana, an important political and spiritual leader of the quilombola people.

A quilombola from the Carrapatos da Tabatinga Community, in the state of Minas Gerais, Sandra Maria da Silva Andrade has over 20 years’ experience as a quilombo activist. She is one of the most active leaders in the state and a founder of the Federation of Quilombola Communities of Minas Gerais (N’Golo). She is currently the executive coordinator of the National Coordination for the Articulation of Rural Black Quilombo Communities (CONAQ). A child of Yoruba deity Xangô, Andrade is the daughter of Dona Sebastiana Geralda, the renowned Mother Tiana, an important political and spiritual leader of the quilombola people.

“My voice within the Coalition is the voice of the over 6 million quilombolas existing in the country, because we have lived with racism for 500 years. The Coalition exists today to make these voices visible and, through the Coalition, we are letting the world know about the structural racism we suffer from within this country. The need to yell and give visibility to racism is because Brazil has always projected abroad that there is no racism here. But we are here today proving that this is not true, through demonstrations of rights violations, giving visibility to this veiled racism that has always existed here. We come together to echo the voice of the black people.

The current [federal] government came to take away hard-won rights. In three months, they destroyed 24 years of work developed by CONAQ. All the government agencies that had the competence to work with the quilombola population were disbanded. The government has also been incentivizing the invasion of our territories. President Bolsonaro was very clear before he was elected. He said that he would not title any land for quilombolas and he is, in fact, fulfilling his promise. He talks about us quilombolas like animals in his speeches and his use of racist lines is constant. We knew we were going to face a tough fight, but we thought that through the justice system we would be able to guarantee some rights. However, with this government, not even the justice system has been able to stop these violations. We are on our own… like we so often say, it is ‘by us for us.’

The Black Coalition for Rights and its ‘As Long As There is Racism, There Will Be No Democracy,’ campaign, launched in June 2020, came at the exact and crucial moment to denounce all of this. This struggle cannot be ours alone. The anti-racist fight belongs to society, that needs to embrace this fight. Racism does not start with us.”

“Even When They’re Not Activists, Black Women Are On the Move”

Known inside the Black Movement lovingly as “Zezé,” Maria José Menezes, from the state of Bahia, is one of the greatest references for black women in the fight for rights and against racism and sexism. A Candomblé practitioner with a degree in Biology, she was one of the University of São Paulo Black Awareness Center’s leaders to spearhead the struggle for affirmative action policies within the university. Today, Menezes participates in the MAHIN collective and is one of the organizers of São Paulo’s Black Women’s March, representing the organization in the Black Coalition for Rights.

Known inside the Black Movement lovingly as “Zezé,” Maria José Menezes, from the state of Bahia, is one of the greatest references for black women in the fight for rights and against racism and sexism. A Candomblé practitioner with a degree in Biology, she was one of the University of São Paulo Black Awareness Center’s leaders to spearhead the struggle for affirmative action policies within the university. Today, Menezes participates in the MAHIN collective and is one of the organizers of São Paulo’s Black Women’s March, representing the organization in the Black Coalition for Rights.

“Even when they’re not activists, black women are on the move. You don’t necessarily have to be part of a movement to fight. Reading Sueli Carneiro’s thesis, for example, I learned that Brazil’s Unified Health System (SUS) would not exist today without the struggle of women from the peripheries. And who are these women? They’re us, black women, who, without any kind of assistance, fight for universal public health. Consequently, it is crucial to value the voices of black women as subjects. My voice in the Coalition for Black Rights is that voice! It is a voice that contemplates the periphery from the perspective of black women and of urban youth, the main victims in a racist country.

Being a black woman brings a special kind of power, and that makes me very proud. To be in the Black Coalition for Rights in such a role is to live in a space of learning and to have my voice echo from an ancestral movement of black women, who have, historically, and who still face the structure of a nation controlled by segments of colonial society, that act as if the country were a great estate. Whiteness in this country benefits from the capital, the labor force and public rights that should be at the service of and for the benefit of all, without unequal access. It is for this reason that, with the Coalition, people question narratives and ask themselves: ‘What kind of democracy is this, where racism is the main agent?’ That question… that issue needs to be confronted.

It’s absurd that, in a country like ours, where racism generates inequalities and asymmetries, it does not figure on the main political agenda, [especially] when you look at Brazilian society and see that all indicators have color and gender. The Coalition came about within the context of attacks—on rights, of the crimes of the Bolsonaro administration and of the strengthening of neo-fascism—as a resistance to that picture, for we feel that, with this government, our lives, that are already vulnerable, would be even more at risk. The Coalition is one more response among many of Brazil’s Black Movement.

It is important to say that the Brazilian Black Movement always acts in a coordinated manner and that there are many other organized black women’s movements and black movements in the country. The Black Coalition for Rights is but one more contribution that adds alongside the entire black movement composed of many groups and collectives.”

“I Speak from the Place of a Black Northeastern Woman”

Born and raised in Recife, Monica Oliveira has been an activist since she was 15, and in Brazil’s Black Movement for over 30 years. She’s been a part of different black organizations, from the Unified Black Movement to the Black Observatory. Oliveira has a degree in social communication and is currently the Finance Coordinator of the Pernambuco Network of Black Women and member of the Black Women Network of the Northeast, representing the latter in the Black Coalition for Rights.

Born and raised in Recife, Monica Oliveira has been an activist since she was 15, and in Brazil’s Black Movement for over 30 years. She’s been a part of different black organizations, from the Unified Black Movement to the Black Observatory. Oliveira has a degree in social communication and is currently the Finance Coordinator of the Pernambuco Network of Black Women and member of the Black Women Network of the Northeast, representing the latter in the Black Coalition for Rights.

“I speak from the place of a black woman from northeastern Brazil. That is an important statement because Brazil is as vast as a continent and racism is also reflected in regional inequalities.

From a proportional point of view, the Northeast is Brazil’s blackest region. I speak from this viewpoint because intersectionality, which is a way of analyzing inequalities, is a reality felt in the day-to-day encounters that intersect the different realities of discrimination, whether by race, gender and class, but also region. For this reason, we often strain our relationships with leaders from Brazil’s South and Southeast to affirm our political positions. Thus, I speak from the viewpoint of a region that is very impoverished and exploited, but also from a region that is beautiful and that has a historic trajectory of struggle; where the Quilombo dos Palmares was located, where a fight [for freedom] was waged for nearly 100 years. I speak from a city where the head of Zumbi dos Palmares was staked in front of a church. I speak from the position of black and Northeastern identity.

The Black Coalition’s manifesto ‘As Long as There is Racism, There Will Be No Democracy‘ is a historical landmark of great magnitude, as important as the 1978 Black Unified Movement manifesto, when the Black Movement created an organization at the height of the military dictatorship that had prohibited the discussion of racism in Brazil and removed the notion of color, for example, from public texts. Despite changes and advances that we’ve had over the years, the cruel inequality of racism in Brazil, the abyss between whites and blacks, has not undergone any significant change. Furthermore, the model of democracy we have in this country is one that is unrealized, that has never been a true democracy where everyone could participate in the country’s decisions. That is exactly what the manifesto, and above all, the political advocacy of the Coalition spotlights: the racism present in our society.

And that doesn’t apply solely to conservative political forces, but also to progressive ones on the Left, that has, over the years, stated and agreed alongside the Black Movement that racism structures inequality in Brazil, without this anti-racist statement translating into policy, as the black population continues to be impeded from spaces of decision-making and power. Therefore, anti-racist statements [by progressive forces] do not translate into changes in attitudes, for example, inside political parties, programs and governmental public policies when the Left is in power. As long as this is the case, it is not possible to say that Brazil is a true democracy. Either racism is truly seen as structural and becomes a pillar for debate and policy-building to achieve equality, or we need to evaluate: what country is this that we are building? Who is this democracy for?

We from the Black Movement do not want to and will not return to that so-called normalcy of racism, patriarchy, genocide, hunger and poverty that existed before the pandemic and that continues to exist… We are living a political moment where we need to break with the normalization of racism. And that rupture needs to happen now, because we are in a dire situation and, for us, it is no longer possible that this country continues to live with this level of continuous racial conflict. The Coalition is not something new, but the continuation of previous organized black movements that have been vying for years for a nationwide political project.”

About the author: Tatiana Lima is a journalist and popular communicator at heart. A black feminist, member of Complexo do Alemão’s Researchers in Movement Study Group, she is currently special reporter with RioOnWatch. A fair-skinned black woman, born and raised in a favela, Lima currently lives in Rio’s periphery and is a doctoral student at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF).

About the artist: David Amen was born and raised in Complexo do Alemão, is co-founder and communications producer at the Roots in Movement Institute, a journalist, graffiti artist, and illustrator.

This is the fourth article in a series of four on Brazil’s Black Coalition for Rights and is also the latest contribution to our award-winning reporting project, Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.