This article is part of a series created in partnership with the Center for Critical Studies in Language, Education, and Society (NECLES), at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), to produce articles to be used as teaching materials in Niterói public schools.

The Covid-19 pandemic increased social inequalities globally. Here in Rio de Janeiro, education was one of the most affected areas. As classes were temporarily suspended and then carried out online, the number of children not attending classes increased, especially among those living in urban peripheries. In an attempt to stop more students from abandoning their studies, creative initiatives were set up or expanded, such as the Knowledge Crate and the Inclusion Project.

With teaching going online, children and teenagers who live in Brazil’s favelas and urban peripheries saw their access to school affected by their lack of Internet access. According to the study “Facing Up to the Culture of School Failure,” around 5.5 million students were left without access to education in Brazil, almost double 2019 figures. The survey, carried out by Unicef in 2020, revealed that around 1.4 million students aged between 6 and 17 dropped out of school across Brazil. The survey also looked at the absence of school activities. Despite being enrolled and not being on break, 4.1 million students did not receive any schooling in 2020.

Given this situation, NGO Nóiz developed creative education and cultural initiatives to support residents in the City of God favela, in Rio’s West Zone. In 2018, the project received help from dermatologists to treat children suffering from skin problems often caused by the open-air sewer in Brejo, a neighborhood in the favela made up of precarious homes without access to water and electricity.

With the help of three friends, the president of the organization, André Melo, developed a proposal that would go beyond welfare assistance. “We are very aware that donations are just a palliative measure. You give someone a plate of food and they will go hungry again. Welfare assistance is important, but it’s never been our focus. We’ve always believed in training people, whether through sport or culture. We believe in a more expansive approach.”

Nóiz’s first base was a basic wooden shack in Brejo. In 2019, thanks to partners, the team gained access to a deserted building, long abandoned by public authorities in the Karatê area. They organized a graffiti event to add some color to the walls of the new building. Despite the basic facilities, the group sought to preserve its identity based on education and development, offering a variety of activities such as martial arts, tech courses and a college exam prep course, among others. With the onset of the pandemic, the organization distributed face masks, hand sanitizer, and baskets of basic foodstuffs. By the end of 2021, Nóiz’s team had given out 20 tons of food.

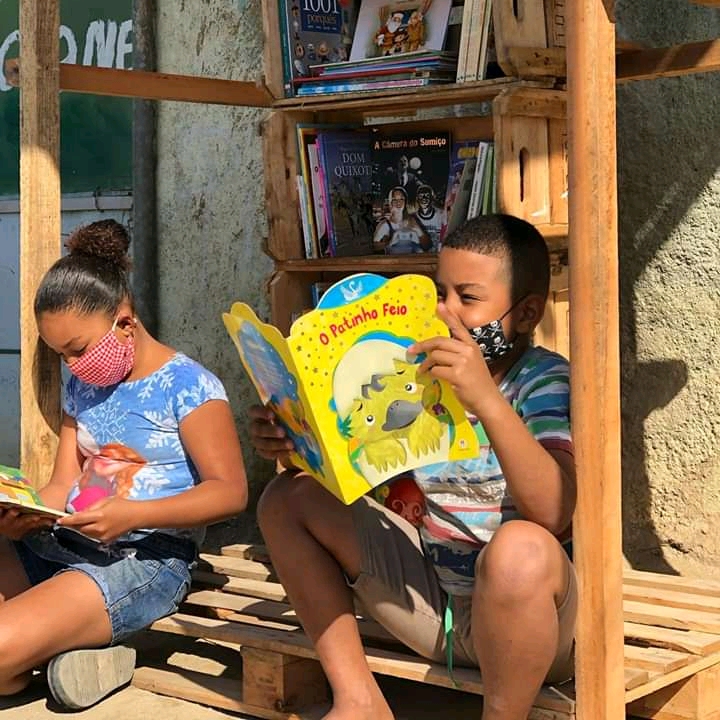

During the pandemic, Nóiz decided to keep running its education programs due to strong appeals from parents of the 60-plus children involved with the project. One of these programs is the Knowledge Crate. The idea of creating miniature libraries emerged in July 2020 when Nóiz volunteers joined forces to reduce students’ idle time in City of God. In total there are four fixed points, located in Brejo, Pantanal, Tangaré, and Apês. The mini-libraries received over 1,500 donated books through social media campaigns and from people interested in helping. Locals can borrow the books or read them on the spot.

The Knowledge Crate is currently located in the Frederico Eyer Municipal School, with reading groups to increase interaction between students and teachers. André Melo notes that the initiative has succeeded in encouraging reading within the community. “When we put a crate [somewhere], the sparkle in kids’ eyes is contagious. Everything is a question of opportunity and encouragement,” he says.

The initiative helped many parents—including Giovanna Ferreira, a waste picker who has two children involved with Nóiz. “I was scared of leaving my daughter alone because of her epilepsy; now I leave her because I trust the team. Duda is eight and is learning to write her name. The NGO is helping her a lot,” says Ferreira.

The initiative helped many parents—including Giovanna Ferreira, a waste picker who has two children involved with Nóiz. “I was scared of leaving my daughter alone because of her epilepsy; now I leave her because I trust the team. Duda is eight and is learning to write her name. The NGO is helping her a lot,” says Ferreira.

While the Knowledge Crate has been helping maintain some learning among students during the pandemic, official schooling continues to present a series of obstacles for those living in the periphery. “The teacher created a WhatsApp group and sent homework to be copied out in notebooks. We had to hunt down a Wi-Fi signal so the kids could do their homework. Before, the school gave out food vouchers, now they only give them out to people with multiple issues,” says Ferreira.

The Impacts of Staying Out of School

Generally, school flight occurs when students do not enroll to continue their studies the following year, different from dropping out, which is when they stop attending during the school year. Although education is included in Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, school flight and school dropout are realities not yet resolved in Brazil.

Rute Andrade, a specialist in neuro-psychopedagogy, warns that school dropout rates can have consequences which tend to multiply if not taken seriously by governments. “The lack of continuous education is a problem in which public authorities should intervene. The classroom increases self-esteem, provides security, and teaches how to have a social conscience in practice. To be left out of school can be a painful process which will be hard to overcome as an adult without seeking adequate professional help. Dropping out of school and the associated prejudice can make it difficult to have a successful career,” she explains.

With the motto “What we don’t know, we learn,” the couple Élida Nascimento and Marcos Júnior founded the Inclusion Project in the heights of the Morro da Aparecida favela in São João de Meriti, a municipality in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region. The idea of promoting youth education emerged in 2014. Using an approach based on the theory of multiple intelligences and personalized help, the Inclusion Project delivers school tutoring, psychological support, sports, and vocational courses.

With the motto “What we don’t know, we learn,” the couple Élida Nascimento and Marcos Júnior founded the Inclusion Project in the heights of the Morro da Aparecida favela in São João de Meriti, a municipality in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region. The idea of promoting youth education emerged in 2014. Using an approach based on the theory of multiple intelligences and personalized help, the Inclusion Project delivers school tutoring, psychological support, sports, and vocational courses.

After identifying the education gap that affects favela residents, Nascimento, a teacher in Rio’s municipal school system, decided to intervene. “In school corridors, I often overheard people saying that a child wasn’t capable of learning. This really disturbed me, so I started to think about bringing classroom teaching methods to my community,” she says.

Last year, the organizers had to reinvent the Inclusion Project’s activities. With the help of volunteers, a crowdfunding campaign was launched aimed at donations of baskets of organic basic foodstuffs. The idea led to the creation of the Solidarity Market. After much research, the project found a way of increasing immunity among its beneficiaries by incentivizing healthy eating habits with fruit and vegetables. In total, 500 baskets were distributed.

Last year, the organizers had to reinvent the Inclusion Project’s activities. With the help of volunteers, a crowdfunding campaign was launched aimed at donations of baskets of organic basic foodstuffs. The idea led to the creation of the Solidarity Market. After much research, the project found a way of increasing immunity among its beneficiaries by incentivizing healthy eating habits with fruit and vegetables. In total, 500 baskets were distributed.

Nascimento stresses that the initiative has met needs which go well beyond education: “We noticed that a lot of young people had abandoned their studies. When the rules started being relaxed we decided to go back to holding classes at our base. Many children don’t just come here [to the Inclusion Project] to learn, but also to eat. A lot of children weren’t eating properly, consuming mostly processed foods really quickly… An unhealthy diet negatively affects educational development. Vitamins, proteins, and nutrients are essential for physical and pedagogical training.”

An Uncertain Return to School

Also located in Baixada Fluminense, the municipality of Duque de Caxias is the third most populous in the state of Rio and hosts approximately 809 industrial businesses.

The Merity Proletarian School was founded in 1921 to serve the region’s rural community and represents a milestone in Duque de Caxias’ educational history. Educator Armanda Álvaro Alberto, inspired by the Montessori method, brought innovation to the pedagogy of the time and sought to transform the school into a center for the development of teaching for children.

Notably, the school was one of the first in Latin America to provide meals. Because of this, it became known as the Escola Mate com Angu, or the tea and corn gruel school. Alberto always paid attention to the children’s health, offered a full education, and got students to assist in the gardens and animal rearing.

For quite some time during the pandemic, many public secondary schools functioned through hybrid teaching—part in-person, part virtually. The Anísio Teixeira National Institute for Educational Studies and Research (Inep) released a study based on the school census carried out between February and May 2021, which revealed that 90% of schools did not return to classes in the 2020 academic year. Among federal-run schools, the percentage was 98%, followed by municipal schools (97%) and state-run schools (85%).

Rose Cipriano, who has been a teacher in Duque de Caxias’ municipal schools for 24 years, is critical of the teaching methods adopted during the pandemic: “With school closures, access to resources became even more precarious. While private schools moved online, this did not happen with our students [due to the lack of] access to computers. When [a student] has a mobile phone, it is used by the entire family. What we’re passing on to them as virtual schoolwork is not prepared, it’s completely improvised. This experience is very complex. We communicated with students over social media. We asked ourselves if a like on Facebook could be considered class attendance.”

In Rio de Janeiro’s municipal schools, in-person classes became compulsory again in November 2021. In an announcement made on October 26, current education secretary Renan Ferreirinha said: “It’s very important that we guarantee our students have access to education and the return to compulsory in-person classes is an important step in this direction.”

Cipriano, who leads the Caxias chapter of the Rio de Janeiro State Union of Education Professionals, says of in-person teaching: “Students were hit with the shock of remote teaching and returning [to the classroom] could have a real impact. We need institutional programs, campaigns or sound trucks to raise awareness about the importance of education. Active searches of homes need to be carried out in a way that respects each person’s individual reality.”

The reasons for leaving school vary by region. Some students abandon their studies because of lack of support, precarious public transport, or even because of bullying. Community initiatives continue to lovingly carry out their work like an ant colony, once again following the principle of “By Us for Us.” But it is clear that, right now, it is crucial that public policies be designed to halt school dropouts, which become a fatal problem as the years progress.

About the author: Beatriz Carvalho was born and raised in Vilar dos Teles, São João de Meriti. She is a journalist, media-activist, feminist, and founder of Mulheres de Frente.