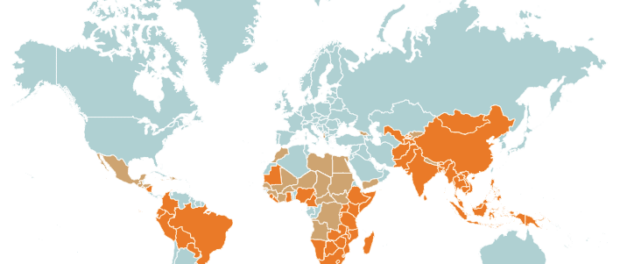

On March 9, the Land Portal and the Solutions Journalism Network realized the webinar “Communication About Land and Environmental Issues: The Solutions Journalism Approach” with attendees from Nigeria, Tanzania, Namibia, Rwanda, South Africa, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Mozambique, Colombia, Ecuador, Brazil, Belize, Canada, Spain, the Netherlands, Sweden, India, Philippines, Bangladesh, Singapore, and the United Arab Emirates.

The goal of the webinar was to better understand the role of journalism in inclusive access to land and environmental protection. Another objective was to share how the Land Portal could be a useful tool to collect data, produce knowledge, and defend land rights globally. The partnership between the Land Portal and the Solutions Journalism Network aims to reach and publicize new solutions to environmental and land issues, as well as to challenge perceptions about, interest in, and public engagement with these themes.

The goal of the webinar was to better understand the role of journalism in inclusive access to land and environmental protection. Another objective was to share how the Land Portal could be a useful tool to collect data, produce knowledge, and defend land rights globally. The partnership between the Land Portal and the Solutions Journalism Network aims to reach and publicize new solutions to environmental and land issues, as well as to challenge perceptions about, interest in, and public engagement with these themes.

Among the webinar participants were Romy Sato, coordinator of the network of researchers of the Land Portal; Nieves Zúñiga, researcher and engagement consultant for the Latin American Land Portal; Alfredo Casares, Spanish journalist from the Constructive Journalism Institute; Swait Sanyal Tarafdar, independent solutions journalist based in South India; and Mavic Conde, a Filipina expert in agroecology, the environment, and community innovation in food systems.

Romy Sato, responsible for coordinating the Land Portal’s network of researchers, explained that the portal was founded in 2014 to share democratic land and environmental community solutions around the globe and can be an important source of information and data on actions featured through solutions journalism. It has over 66,000 publications related to land and environmental issues, with a series of thematic reports and compiled material on the themes: Land Governance on the African Continent, Indigenous Land Rights, and Territorial Governance and Gender. In addition, it is possible to filter the publications by content, location, author, and date, among others.

Romy Sato, responsible for coordinating the Land Portal’s network of researchers, explained that the portal was founded in 2014 to share democratic land and environmental community solutions around the globe and can be an important source of information and data on actions featured through solutions journalism. It has over 66,000 publications related to land and environmental issues, with a series of thematic reports and compiled material on the themes: Land Governance on the African Continent, Indigenous Land Rights, and Territorial Governance and Gender. In addition, it is possible to filter the publications by content, location, author, and date, among others.

For Nieves Zúñiga, some of the biggest challenges related to the environment in Latin America are deforestation, climate change, agriculture, and plastic pollution in the ocean. But with intense and paralyzing news titles, like the 2019 New York Times headline “Climate Change Is Accelerating, Bringing World ‘Dangerously Close’ to Irreversible Change” or the 2021 Guardian headline “Major Climate Changes Inevitable and Irreversible – IPCC’s Starkest Warning Yet,” the public is not urged to act, but to conform to what appears, by the title of the article, to be inevitable, incapable of change. The pessimism and problem focus that dominates the traditional media narrative with an overly dramatic discourse of the inevitable and irreversible negatively affects people and, according to Zúñiga and researchers from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, is one of the main reasons readers reject news stories.

“When we read these headlines, we think: ‘What can a single person like me do to stop these irreversible changes?’ And many people tune out the problem and feel depressed. One study done by the Reuters Institute shows that the main reason people avoid news is because it irritates and depresses them.” — Nieves Zúñiga

Zúñiga explains that knowing there is a public demand for hope and solutions, in addition to recognizing the potential of journalism in helping realize the world we want, should guide journalists to mobilize their audience to deal with problems and share answers. Solutions journalism is not only about reporting positive things, it’s about telling the whole story focusing not only on problems, but mainly on ways to respond to them. According to Zúñiga, one of the ways in which solutions journalism works is by conducting an in-depth data analysis on potential community solutions.

“Often, environmental journalism is based on scientific research. This is important because it gives credibility, but, on the other hand, at times, it is difficult for many people to connect with science and we lose the chance to bring the story closer to the public’s reality. Recognition of the power of information and journalism in creating a vision of mission in the world is our role in it… how to better report on the environment to mobilize public agency to effectively deal with problems and bring about positive change.” — Nieves Zúñiga

Alfredo Casares, Spanish journalist from the Constructive Journalism Institute, consults on solutions journalism and is author of Time for Constructive Journalism (La Hora del Periodismo Constructivo). The book talks about how to apply constructive, solutions journalism to environmental and land issues. According to the author, “64% of BBC viewers under 35 want to see positive news which deals with solutions to everyday problems. According to the Reuters Institute, young Europeans want to have contact with news that inspires them to the possibility of change”.

For Casares, the most important role of journalists and the media is to present and share solutions to issues that the public thinks to be unsolvable: to report hope, share successes and new ideas. Journalism can lead society to have hope based on facts, leading to mobilization and collective action. He draws attention to the fact that, despite identifying pathways, solutions journalism is not advocacy. It identifies existing solutions without assuming a political or ideological slant.

“In this scenario of lack of access to reliable information, lack of trust in the media and social polarization, rejection of news is one of the consequences. People feel overwhelmed, they feel that we focus too much on conflicts and dramas, that solutions are underrepresented in the media, and we describe the world as a worse place than the one we live in… Our responsibility as journalists is two-fold: one, we, the media, help the population to form an image of the world, but we also help them to make an image of themselves in the world, in addition to the [image] of the role they can play in this society as active citizens and not passive spectators… If we share learning and new ideas, maybe people will feel inspired to take action and really mobilize.” — Alfredo Casares

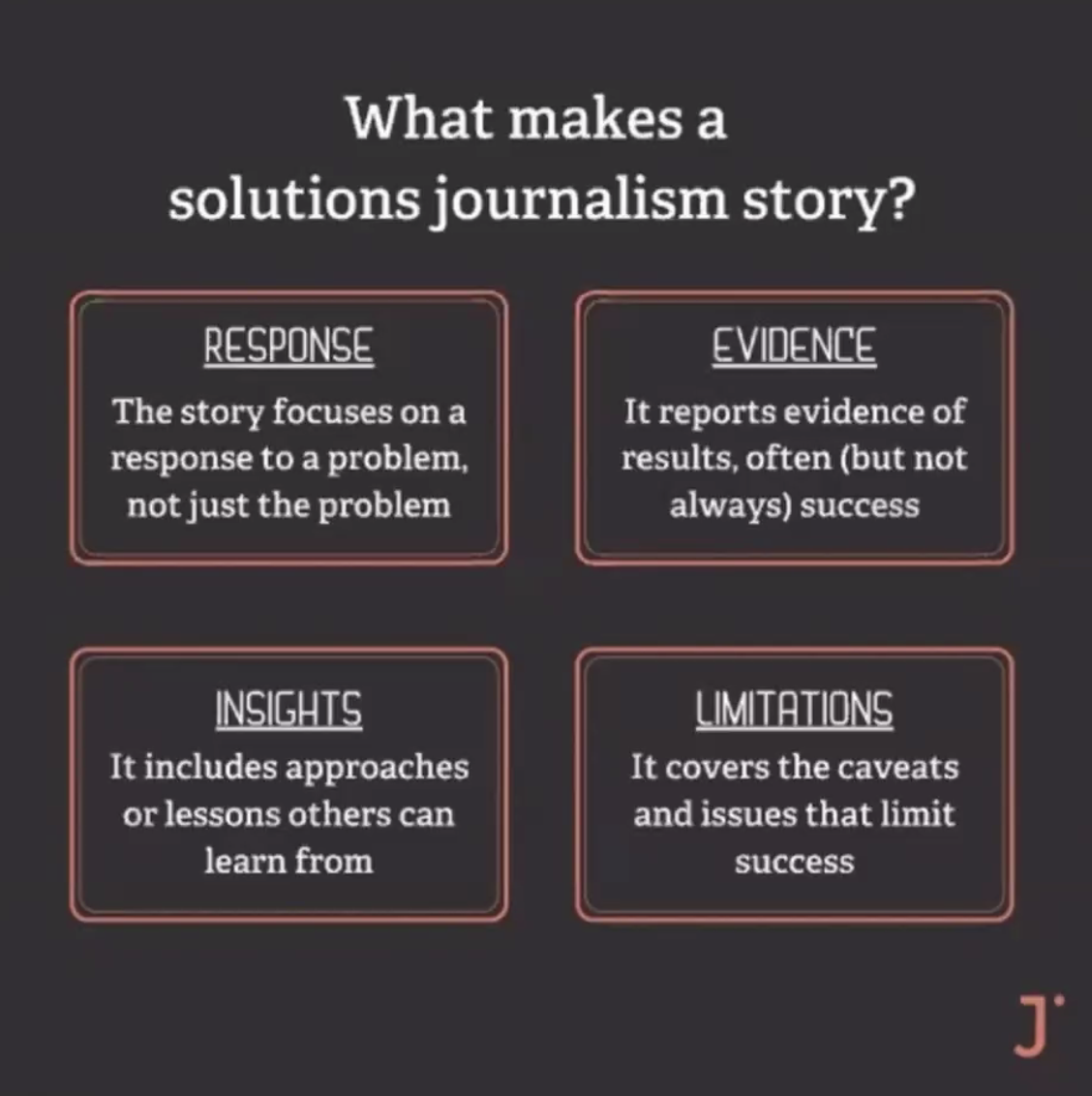

According to Casares, solutions journalism must be accurate, based on evidence that offers hope to society through science and also always responding with innovative ideas to a real problem. This type of journalism prioritizes analyzing the problem through solutions. Evidence of the problem is presented along with ideas for responding to it. According to Casares, it is also fundamental to analyze the limitations of the solutions presented. As a tool for these professionals, platforms such as the Solutions Story Tracker have cataloged over 13,000 community solutions from global society that have made news and can help people around the world.

According to Casares, solutions journalism has positive impacts on journalists and media professionals as well. Writing stories and working on positive and purposeful agendas, many report feeling empowered and encouraged to act because they are one step ahead of the rest of society. They feel motivated to promote a change in the perspective of others and come to understand their work as having a significant social purpose.

“Solutions journalism also covers the problem, but no longer from the point of view of the problem. Rather, from the point of view of the solution… of social knowledge. In solutions journalism you do a better job, because you explain problems better from other perspectives, where you help the reader understand the problem through the answer… Journalism should give us hope, not fear.” — Alfredo Casares

Swati Sanyal Tarafdar is an independent reporter who covers social and climate justice, health and the environment in South India. This region, in addition to being fertile with large agricultural areas, is industrial and suffers from pollution. The territory has conditions that contribute to climate change: deforestation, large numbers of cattle, extractivism, pollution of water, land, and air, garbage, etc. But the stories that she reports are told from the point of view of natural resources, social and environmental justice, of those who suffer and solve problems.

“These people, in their ancestral lands, have been telling us for decades that the environment is suffering. In my work, I try to go to people, talk to farmers, workers, women, to capture their perspectives on the environment. They are the people who are the least heard, but those who can contribute the most, because they are at the base, directly experiencing the impacts of the problem. We already have many displaced by the climate, areas that used to produce are no longer producing, there are droughts or excessive rain. Why do we continue to ignore even the most dire warnings about climate change?” — Swati Sanyal Tarafdar

According to Tarafdar, one of the reasons for the apathy is that there is a disconnect between how we understand environmental problems and how they are reported to society through traditional journalism. A good solution to make the audience care, according to her, is through the sharing of information that motivates and inspires the reader, with local accessible solutions. A journalism that engages is based on four pillars:

- Offers a response (to a problem);

- Contemplates scientific evidence;

- Brings about innovative ideas; and

- Analyzes limitations.

The role of the journalist is to show where this solution is created, how it is carried out, what the scientific principles that underlie the solution are, and how to reproduce it—to show how a solution is close at hand. It is about helping people change their lifestyle, present answers, inspire, entertain, and mobilize communities to create their own solutions. It is about reporting positive stories that inspire real changes. “In my experience, the most impactful stories were those that presented solutions to the reported problems,” says Tarafdar.

“People care more about things that impact and inspire them.” — Swati Sanyal Tarafdar

To Tarafdar, it is a political value of solutions journalism to bring up evidence to debate the political stagnation regarding the problem. Another value is to understand the limitations of community solutions, precisely in order to demand—based on those limits—systemic solutions to be undertaken by the government, making governing authorities accountable.

A criticism of solutions journalism is typically that it diverts attention from the problem and minimizes government responsibility. However, according to Tarafdar, once a solution is identified somewhere, people from similar regions can be inspired and see that change is possible and close at hand. This then helps them hold governments accountable, demonstrating that solutions exist, and that to adopt them is a political choice.

The webinar’s last panelist was Mavic Conde, from the Philippines, an expert in the environment and community innovations in food systems. According to her: “agriculture and land rights are two sides of the same coin.” Agriculture should be at the heart of development, especially in native and campesino territories and, therefore it must have an increasing presence in solutions journalism coverage.

In contrast to global industrial agriculture, agroecology explores the interactions between species by adopting polyculture; democratizing food production and land access; reducing the exploitation of work in the field, land conflicts with native peoples, and environmental degradation; preserving biodiversity, having less environmental and climate impacts; prioritizing food security over profit; and respecting traditional local practices of sustainable production instead of implementation of intensive technology. However, Conde says that it is necessary to state that ecological principles apply to all types of food production, not just organic systems.

In the climate crisis we are living, agroecology can be seen as an excellent solution. It is a process based on four main pillars: ecological balance, social equity, cultural vitality, and economic viability. Agroecology is the management of agriculture as an ecosystem and its principles are cooperation, mutual aid, sustainability, and diversification. It reduces production costs, valuing the local seed bank over industrial food production in large-scale monoculture.

“Above all, agroecology gives the farmer a sense of belonging with relation to the land on which he produces. He realizes that he also is part of the ecosystem.” — Mavic Conde

In regard to solutions journalism, Conde explained that, in the Philippines, people are suffering from broad climate crisis impacts: problems with floods, water contamination, and rising temperatures. To respond to environmental issues in the Philippines, solutions journalism is a powerful path. According to her, news reports focused on solutions have the greatest impacts in the country.