From the closing down of printers to the lack of profitability of favela media, grassroots communicators have faced the challenge of keeping community journalism alive in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro for the past 40 years.

According to data gathered by the Piratinga Communications Center (NPC), the newspaper O Favelão—The Voice of the Favelados continues to be in print. O Favelão was founded in 1978 by the Favelas Pastoral Committee during the struggle against forced evictions in the favela of Vidigal. While it is still in circulation, albeit irregularly, the project in its original format, in which residents play leading roles in the political voice of the favela, ended in 1986.

The challenge of the newspaper to encompass all of Rio’s favelas was bold, especially considering it sought to represent every favela resident via its slogan “voice of the favelados.” However, the end of the newspaper’s journalistic project in print format is directly linked to the end of its financial viability, guaranteed at the time by the Ford Foundation. Producing a print newspaper is expensive: beyond the work and fair payment of community journalists, there are the costs of photography, printing, and newspaper distribution.

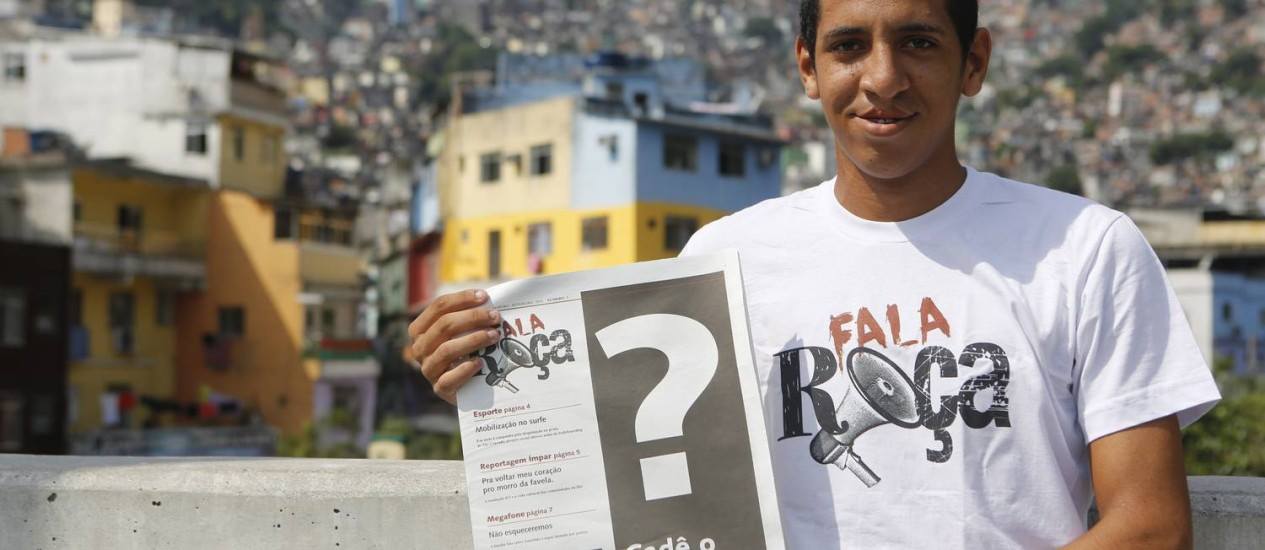

The sustainability of community and grassroots journalism, especially in printed form, continues to be fought for by journalists and community communicators in the favelas to this day. Fala Roça, for example, is a community newspaper created by a group of young people in Rocinha, Rio’s single largest favela, who participated in creative activities at the Networks for Youth Agency program. Its first print edition was published in May 2013.

A print publication was thought of as a necessary to reach the favela’s offline population. The newspaper’s name pays homage to the population of northeastern Brazilian origin in the favela. With advances in technology, Fala Roça was revamped and created a website. Although it went on to produce coverage in digital and video versions, it has not given up its print circulation. However, the production and distribution of the print newspaper is irregular due to difficulties with financial sustainability.

A print publication was thought of as a necessary to reach the favela’s offline population. The newspaper’s name pays homage to the population of northeastern Brazilian origin in the favela. With advances in technology, Fala Roça was revamped and created a website. Although it went on to produce coverage in digital and video versions, it has not given up its print circulation. However, the production and distribution of the print newspaper is irregular due to difficulties with financial sustainability.

With a permanent five-person team, the newspaper managed to obtain a central office in 2021 and delivered a course on grassroots communication to train new community journalists. However, the eight-page full-color print version of the newspaper has not circulated in the favela since October of last year.

“We’ve had to cut costs, but we’re working on it coming back. We don’t think we can afford to have yet another source of critical information out of print in 2022, an election year. We’re experiencing a surge of disinformation. The print version reaches people beyond the Internet, inside their homes, as a trustworthy source that has maintained credibility over the years,” stressed Michele Silva, director of Fala Roça.

“We’ve had to cut costs, but we’re working on it coming back. We don’t think we can afford to have yet another source of critical information out of print in 2022, an election year. We’re experiencing a surge of disinformation. The print version reaches people beyond the Internet, inside their homes, as a trustworthy source that has maintained credibility over the years,” stressed Michele Silva, director of Fala Roça.

She added:

“It is crucial that local news outlets continue to exist, showing the view of grassroots journalists so they can continue to inform and oppose what the mainstream media says, and cover what the bigger publications refuse to.”

Fala Roça has a circulation of 10,000.

The costs to print a physical newspaper vary according to the prices charged by printers, and there has been an increase recently because “the price of paper is tied to the dollar,” as explained by Michel Silva, editor of Fala Roça. The high value of the dollar led to the closure of various printing businesses in Rio de Janeiro, which increased the costs required to print the newspaper even further.

According to Silva, “From an advertising standpoint, it’s not easy to monetize a newspaper made in the favela because brands and local commerce don’t understand the reach these types of media have within the favela.” This applies to both the costs of production in an online format and efforts to achieve financial sustainability in print. Still, according to Silva, the circulation of print news in the favelas “still has the important power of representation and dialogue with the favela.”

Fala Roça has a permanent crowdfunding campaign, with donations ranging from R$10 (US$2) to R$80 (US$16) and exclusive rewards for each level of support. This model for management and sustainability has been growing among independent media initiatives. In addition, the group applies for financial support through grants and sells advertising space.

However, the income generated is not enough to support the production costs of the print newspaper. Currently, the entire community media operation, including its online version, runs the risk of being paralyzed due to a lack of funding needed to pay the salaries of its five-person team.

Fala Roça is currently one of Rocinha‘s most important community media: it fought hunger and saved the lives of residents during the coronavirus pandemic, distributing hygiene kits and basic food parcels. The newspaper was also responsible for the 2020 scoop which exposed the installation of a CT scanner in the parking lot of the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, the religious congregation of former mayor of Rio de Janeiro, Marcello Crivella.

As a community news organization, Fala Roça is also the cultural voice of the favela, responsible for the Cultural Map of Rocinha. “If for Google, Microsoft, and the city we are merely green smudges that signal a forest, our local mapping reflects the reality of many local life stories,” said the newspaper’s editorial. An updated version of the cultural map is due to be launched shortly.

Print Newspapers in the Favelas

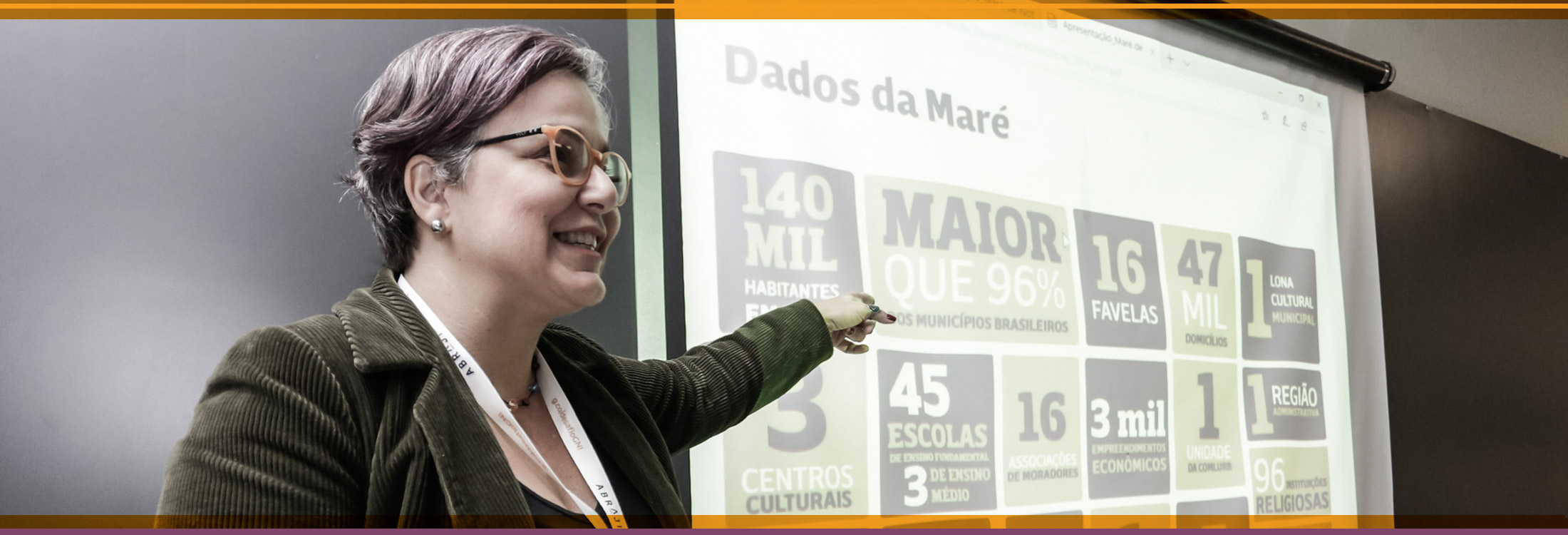

According to Dani Moura, editor of Maré de Notícias, from the Maré Complex of favelas in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone, print newspapers in the favelas “have a lot of relevance because they serve an audience that has no access to the Internet.” She said that the print version of Maré de Notícias, for example, is the “only source of quality, critical information for the elderly population throughout the favelas [that make up Maré].” Maré de Notícias celebrated its 13th anniversary in 2022.

Maré de Notícias, whose name was chosen by residents and literally translates as “tide of news,” has a mixed team made up of Maré residents and members of community NGO Redes da Maré. The newspaper is an initiative of the latter, an organization that has worked for over 20 years producing knowledge and developing projects to guarantee effective public policies which improve the lives of the residents of the 16 favelas that make up the complex.

The only time the newspaper hasn’t published a printed edition due to a lack of funds was for a period of seven months. During the pandemic, the production and circulation of the newspaper was suspended for three months in 2020 and two months in 2021, an editorial decision due to the high risk of exposure to coronavirus. The newspaper has a circulation of 50,000 according to the editor and includes a digital version that is available for download.

“We currently have several channels of sustainability: we have applied for many grants and have active donations campaigns. We also have various partners with whom we exchange content, information, and are investment sources. Our challenge today is to cover the 16 favelas with technical and efficient journalism, considering our size and budget. Still, we’re sure we’ll get there through the training center we have set up this year.” — Dani Moura

The distribution of the newspaper begins every first business day of the month and relies on twelve distributors. The team starts to develop grassroots story ideas during distribution. The newspaper is delivered from alley to alley, corner to corner and in the main streets of the favelas. During delivery, the team receives suggestions for what to cover next. The print newspaper in the favelas is a living, evolving process.

René Silva, founder of Rio de Janeiro’s most famous print and online favela newspaper, Voz das Comunidades, emphasizes that print has a different role from online publications and must continue. “A lot of people in the favelas still get their information from large news outlets that, unfortunately, are very biased.” To Silva, the circulation of print news in the favelas guarantees the democratization of access to information, as “there are many places in the favelas today that still do not have Internet, whether broadband or cell phone carriers.”

René Silva, founder of Rio de Janeiro’s most famous print and online favela newspaper, Voz das Comunidades, emphasizes that print has a different role from online publications and must continue. “A lot of people in the favelas still get their information from large news outlets that, unfortunately, are very biased.” To Silva, the circulation of print news in the favelas guarantees the democratization of access to information, as “there are many places in the favelas today that still do not have Internet, whether broadband or cell phone carriers.”

The newspaper began in 2005 with a circulation of 100 copies that Silva delivered door-to-door. Today, it has a circulation of 15,000 and is distributed free of charge in Complexo do Alemão and Penha, in Rio’s North Zone, and in Vidigal, in the city’s South Zone, where the newspaper’s second office is located.

The print version of the newspaper did not circulate on several occasions, due to lack of funds or editorial direction. This occurred between 2011 and 2014, with the military occupation of the Alemão favelas when the decision was made to use the newspaper’s websites and social media accounts as channels of communication about the occupation. Amid the media visibility during the military occupation, the online version of the newspaper denounced violations and a lack of effectively implemented public policy, achieving widespread visibility.

Day to day, Voz das Comunidades’s Twitter posts produce a significant impact on the demands for rights, responding quickly to the community’s problems due to the ability of social media to publicly expose authorities such as mayors, governors, and secretariats.

In 2015, the print version of the newspaper returned, financially supported by the sale of local advertising to retailers and large brands such as Coca-Cola. However, this did not last long, and the print newspaper stopped circulating again due to a lack of funding. Between closures and reopenings, the print version of Voz das Comunidades celebrated its 17th anniversary in August 2022.

In this new 15-page iteration of the newspaper, community journalists draw attention to information on the most important topics for favela residents. Subjects include health (with an emphasis on vaccination), education, security, a lack of public services (such as water shortages), politics, entertainment, and sports.

“We have returned to the print version of Voz das Comunidades so that more people can have access to it. In general, we need to bring these debates—the issues of politics, gender and race—to people in the favelas and to all localities within favelas. We work through these issues in the print version of Voz das Comunidades, as well as the social problems of our daily lives, of our day-to-day reality within the favela.” — René Silva

Voz das Comunidades continues to be one of the main news sources about the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. With a print version, a website, and now a news app for smartphones, it publishes daily stories on the day-to-day life of favelas.

For Gizele Martins, a grassroots journalist and Ph.D. student in Communication and Culture at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) with more than 20 years of experience in Maré, to speak of community media is to contemplate the development and quality of information for favela residents, as well as work and survival.

“When we talk about information, we’re talking about work that needs to be continued beyond the funding received for a certain project. Generally, social projects have a beginning, middle and end and a community publication does not. It needs to be continuous, not irregular, just like the big media outlets and newspapers that have been around forever.” — Gizele Martins

Martins worked for the O Cidadão—Mídia Comunitária newspaper for 15 years. The outlet was responsible for creating the term “mareense“ as an identity for the residents of the group of favelas that make up Maré. To Martins, the lack of public resources for community media is the main reason for them not existing in TV, radio, and print formats, as well as online. “We don’t have the public funds to finance this media. We don’t have the equipment or funding support to pay the bus fare so a journalist can travel around. We’re lacking on all fronts.”

Martins worked for the O Cidadão—Mídia Comunitária newspaper for 15 years. The outlet was responsible for creating the term “mareense“ as an identity for the residents of the group of favelas that make up Maré. To Martins, the lack of public resources for community media is the main reason for them not existing in TV, radio, and print formats, as well as online. “We don’t have the public funds to finance this media. We don’t have the equipment or funding support to pay the bus fare so a journalist can travel around. We’re lacking on all fronts.”

In addition, Martins says that: “We’ve had years and years of elections and I’ve never heard a single candidate propose a bill that guarantees sustainability for favela-based community media. There’s been nothing in support of our voice from the favelas.”

According to the Community Journalism Map, a georeferencing platform produced by DataLabe—the first data science laboratory in a favela—that compiles community journalism sources in Brazil, there are 40 community-based news outlets in Rio de Janeiro.

The platform is collaborative and any initiative that fits into the established criteria can register and participate, listing community journalism initiatives in peripheral territories. The first survey took place in 2016.

The starting point for DataLabe’s mapping process was the database published in 2014 by the Right to Communication and Racial Justice project. Conducted by Observatório de Favelas, the project mapped 118 alternative, community-based news sources in Rio’s metropolitan region.

One of the initiatives highlighted on the map was the print newspaper A Voz da Favela, which has been published by the Favela News Agency (ANF) for over 10 years. With a circulation of 100,000 copies per month, the initiative aims for the democratization of information based on freedom of expression and human rights. It is distributed by a team that promotes and delivers the newspapers throughout the city.

The Parliamentary Front for the Democratization of Communication

On June 22, 2021, the Rio de Janeiro Legislative Assembly (ALERJ) officially launched the Parliamentary Front for the Democratization of Communication (FPDC). The front was established by request on March 3, 2022, and consists of eight state deputies: Waldeck Carneiro, Carlos Minc, Eliomar Coelho, Flávio Serafini, Renata Souza, Mônica Francisco, Dani Monteiro and Enfermeira Rejane.

Politically active, the organized social movements in the front fight for the effective application of several state laws including 6892/2014, which guarantees 1% of the state’s public funds for the promotion of community-run radio and TV; 4849/2006, which calls for the creation of a State Council of Communications; 9251/2020, regarding 5G technology in Rio de Janeiro; the State Council for the Protection of Data; and the approval of Proposed Bills 2248/2013, which regulates official government advertising, and 1639/2016, which regulates sports games scheduling on television.

Alongside relevant movements, organizations, and community collectives, the front seeks to build strategies to enable improvements in this professional field and strengthen grassroots, alternative, and community-based, favela journalism.

“The FDPC works to strengthen the recognition given to community and alternative media, which perform an important job but have few opportunities to attract funding that the government and public institutions designate for institutional advertising, which is important to sustain the sector,” explained Deputy Waldeck Carneiro.

It is necessary and urgent to guarantee the existence of this media which not only reports but constructs the reality of their territories. The social function of community-based media should be recognized publicly as part of the city’s immaterial heritage. The transformational potential of community-based media is increasingly clear.