This is the first in a series of four articles about the “Degradation of the Pantanal Carioca,” as Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone wetlands were once known.

“To allow for its conservation and to enhance our species of fauna, this huge lagoon should be handed over to the Confederation of Brazilian Fishermen as a biological lagoon reserve. This institution’s leaders are true patriots for the moral and material assistance they dedicate to the legitimate cause of protecting nature.” — Magalhães Corrêa, 1936

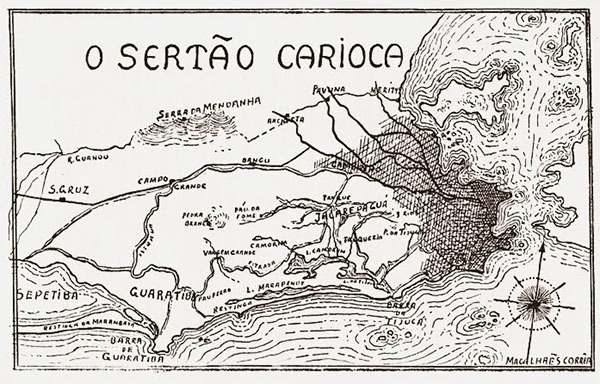

These words were written by Magalhães Corrêa in his 1936 book O Sertão Carioca (“Rio de Janeiro’s Hinterlands“). An artist and professor at the National Museum and at the School of Fine Arts—both of which are now part of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ)—as well as a journalist at the Correio da Manhã newspaper, he documented rivers, lagoons, sandbanks, fauna, and flora with great precision and detail, and also the local habits of the residents of the Jacarepaguá lowlands—a vast territory in Rio de Janeiro, between the Tijuca and Pedra Branca massifs.

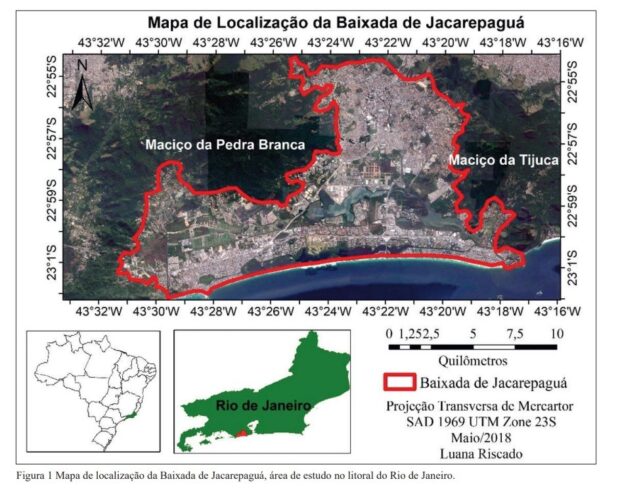

The word Jacarepaguá—yacaré-upá-quá in the indigenous Tupi-Guarani language—means “alligator valley” or “shallow alligator lagoon.” According to technical information by Rio de Janeiro’s State Environmental Institute (INEA), the Jacarepaguá Lagoon Complex in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone is formed by the Tijuca, Jacarepaguá, Marapendi and Camorim lagoons. Measuring around 280km2, the complex’s drainage basin is formed by numerous rivers that run down from the massifs and drain into the lagoons, connected to the ocean through the Joatinga Channel that allows for the exchange of fresh and sea water. The “Pantanal Carioca“, as this wetland region is known, is rich in biodiversity, with 51 amphibians, 24 reptiles, 384 birds, 91 mammals, and 89 fish species.

This region corresponds to Rio de Janeiro’s current municipal Planning Area 4 (AP4). According to the census, AP4 had a population of 909,955 in 2010 and an estimated 1,011,946 inhabitants in 2015.

Geography professor and member of the Baixada de Jacarepaguá Historic Institute (IHBAJA), Val Costa, explains that the word “sertão” used by Magalhães Corrêa to describe the region was once a generic denomination for hinterlands, wild places, inhospitable for mass occupation. This is how Jacarepaguá was viewed at the time. However, Magalhães Corrêa warned us of the area’s potential for environmental exploitation.

“The expression ‘Sertão Carioca’ was intentionally used to depict a Rio de Janeiro inhabited by fishermen, hunters, ax workers, coal workers, mat makers, basket weavers, clog makers, potters, banana plantation workers, dam workers and street vendors. A place with untouched nature, rich with forests, salt marshes and mangroves. However, Magalhães Corrêa warned that this ‘tropical paradise’ risked disappearing in the future and denounced the indiscriminate removal of Atlantic Forest firewood from the region.” — Val Costa

The risk signaled by the naturalist has now become a reality. INEA recognizes that the degradation process of the Jacarepaguá Lagoon Complex is well underway. This is attributed to pollutant dumping from numerous activities in the region. In his book, Magalhães Corrêa reported that the region was experiencing environmental deterioration caused by the uncontrolled exploitation of resources to sustain the growing population of Rio de Janeiro.

Pollution in the Jacarepaguá Lagoon Complex is linked to the lack of public sanitation policies and the demand for land in the region. This has resulted in numerous infill projects and disorganized growth of the AP4. It is therefore necessary to return to the past to understand how pollution in the region arrived at its current state.

From Pau-Brasil Extraction to Infill Sites in the Name of Progress

To understand how the region became populated, we must return to the 16th century when Baixada de Jacarepaguá was occupied by the Tamoios. This indigenous group possessed two great settlements in the region: Guará-Guassú-Mirim (on the banks of the Camorim Lagoon) and Takûarusutyba (in the current neighborhood of Taquara). Between the 17th and 18th centuries, Baixada de Jacarepaguá became known as the “Plain of Eleven Mills” after numerous sugar mills were built in the region. In the 19th century, the slopes of the Pedra Branca and Tijuca massifs were taken over by coffee plantations. From the beginning of the 20th century, the large rural properties were divided into smaller plots of land and the region started housing small and medium-scale polyculture farmers.

With this, the Atlantic Forest in the region underwent various human interventions such as Pau-Brasil extraction, sugarcane harvest, coffee plantation, animal breeding, charcoal production for Rio’s urbanization, and the construction of homes. Regarding the lagoon complex, Val Costa states that isolated anthropogenic interventions were already taking place: “in the 1930s, the region’s bodies of water already received oil from tourist boats visiting the Baixada de Jacarepaguá lagoons.”

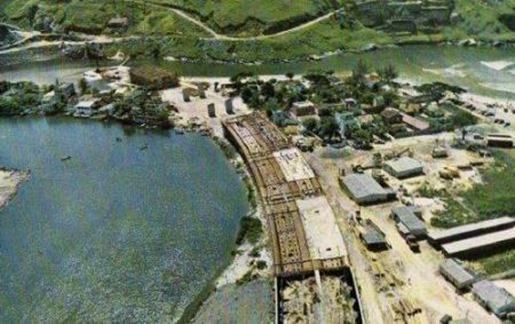

Rio’s South Zone expanded along the coastline throughout the 1960s and reached the West Zone by the end of the decade. As tourism also grew, automotive access to the region was granted. Both the Barra da Tijuca and Itanhangá neighborhoods started attracting people with high purchasing power, which went in accordance with the military dictatorship’s political interests. The decade also brought the new upgrading plan for Brazil’s former capital, known at the time as Guanabara State (which later became the city of Rio de Janeiro). Commissioned to architect and urbanist Lúcio Costa, co-creator of Brasília, the plan aimed for the organized occupation of the region.

The concept involved a big metropolitan axis to balance out built-up and green areas, and integrate the North, South and West zones of the city. In the 1970s, the first large real estate developments appeared in Barra da Tijuca: the Nova Ipanema (1975) and Novo Leblon (1976) apartment complexes, the Carrefour supermarket (1976) and, shortly after, the Barra Shopping Mall (1981). Living in Barra da Tijuca became characterized by large areas occupied by condominiums with residential units, shopping options, their own leisure areas and other exclusive buildings.

This new way of life consolidated the area as an elite destination, a stronghold for the middle and upper classes. People sought a specific lifestyle in the neighborhood. Meanwhile (or rather, as was intentionally part of this project), the scarcity of public housing policies left lower income populations—many of which helped build or worked in the region—in the margins, living in distant regions or by the streams and lagoons. This is how the first favelas, such as Rio das Pedras, were formed in the area. Diverging from what had been planned by Lúcio Costa, infill and drainage projects introduced in the region upset the balance of the local ecosystem.

According to geography professor Val Costa, population growth and disorderly occupation increased organic matter concentration in the lagoon complex. The rivers that flow into the four lagoons began carrying a volume of discharged material that far exceeded the complex’s capacity for purification and waste elimination.

“Numerous socio-environmental problems emerged following the occupation of river banks and lagoons in the area. The lack of adequate surveillance of urban growth in the region resulted in increased illegal activities such as the deforestation of the slopes of the Pedra Branca and Tijuca massifs, the removal of mangroves, the appearance of infilled river banks and lagoons for irregular land use.” — Val Costa

According to the article “Recent urban dynamics of the city of Rio de Janeiro: considerations following data analysis from the IBGE census and municipal urban licensing,” in the last few decades, no area in the capital has grown more than the AP4 in terms of population and housing. Population grew by 47% from 1980-1991, 25.29% from 1991-2000 and 33.33% from 2000-2010. Housing grew by 34.84% from 1991-2000 and 51.21% from 2000-2010.

In July 2022, the local government demolished an irregular building in the Muzema favela that had been constructed by a militia (off duty, vigilante police gang) and was valued at over R$3 million (USD580,00). According to the Technical Coordinator of Special Operations (COOPE), the building was erected on a slope and in a high geological risk area, without containment or a license. COOPE informed that the Muzema region is now continuously monitored and there are 60 lawsuits currently in progress. In the article, Secretary of Public Order Brenno Carnevale stated that 970 demolitions of irregular public space occupations were undertaken in 2021, especially in regions influenced by organized crime.

Despite the urbanization process initiated during the 1960s, it wasn’t until 2009 that the Barra da Tijuca Sewage Treatment Station began operations. State water utility CEDAE is responsible for the municipal sewage system in Rio. The region lacked an adequate sewage system for over five decades, which in turn polluted the lagoon system.

Published in 2001 by the State Secretariat for the Environment and Sustainable Development, studies from the PLANÁGUA project estimate that approximately 700,000 Barra da Tijuca, Jacarepaguá and Recreio dos Bandeirantes residents dumped approximately 40,000 kg of BOD (Biochemical Oxygen Demand) per day in 2000. BOD is a measure of the microbiological respiratory demands of a specific ecosystem to decompose untreated sewage in bodies of water. This compromises the water systems of the region that, nowadays, are bordering on environmentally unsustainable.

This is the first in a series of four articles about the “Degradation of the Pantanal Carioca,” as Baixada de Jacarepaguá, in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone, was once known.

About the Authors:

Felipe Migliani has a degree in journalism from Unicarioca with a focus on Investigative Journalism. Working as an independent journalist and freelance reporter at Meia Hora and Estadão newspapers, he collaborates with the Coletivo Engenhos de Histórias, which investigates and recovers history and memories from the Grande Méier region, and with PerifaConnection.

Fernanda Calé has a degree in journalism from Unicarioca with a focus on Popular Communication as a way of reaching a diverse public in a clear and simple manner. Two years ago, she helped found Agência Lume—a communication agency producing independent journalism in Jacarepaguá, focusing on Rio das Pedras, where she was born.