On November 6, Climate of Change coalition hosted a full-day event at the iconic Rio de Janeiro concert venue, Circo Voador, in Lapa, Central Rio. Four organizations hosted the event (DataLabe, LabJaca, Realengo Agenda 2030, Visão Coop and the CIPÓ Platform) to raise awareness about climate justice.

In the morning and early afternoon, 150 pre-registered participants engaged in various workshops. Then, at 4pm, the event opened its doors to the wider public for two panels focused on climate justice in Brazil.

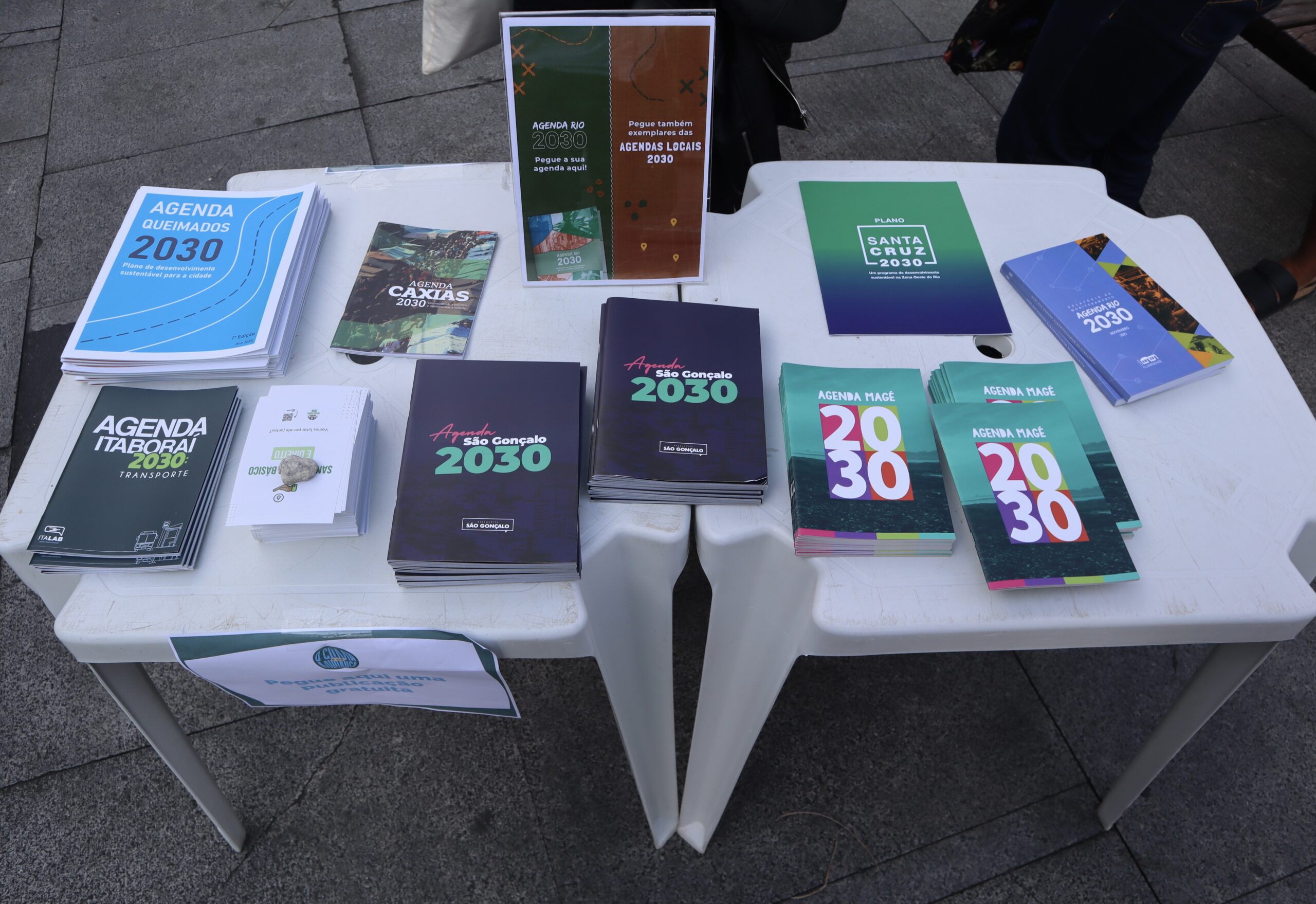

As the public made their way into the concert venue, they passed stalls hosted by the organizational hosts offering information related to climate justice. A Casa Fluminense stall handed out the 2030 sustainable development agendas for different regions located within the Rio de Janeiro metropolitan region.

After audience members took their seats, they were welcomed by Gabrielle Alves from the CIPÓ Platform, a women-led policy institute focusing on climate, governance and peace-building in Latin America and the Caribbean. Alves introduced the program and highlighted the importance of discussions around climate justice, particularly during this pivotal moment in Brazilian history with the recent election of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

Respecting Communities and Embracing Grassroots Solutions

Titled From Local to Global: The Role of the International for Local Solutions in Building Climate Justice, the first panel welcomed guest speakers Eloy Terena, an indigenous lawyer and Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB) representative from the state of Mato Grosso do Sul; Thais Santos, a board member of WWF Brazil; and Junior Aleixo, a researcher and climate justice specialist at ActionAid Brazil to discuss the topic.

From left to right, the panel included the moderator, Eloy Terena, Thais Santos and Junior Aleixo.

From left to right, the panel included the moderator, Eloy Terena, Thais Santos and Junior Aleixo.

As a representative of Brazil’s indigenous peoples, Terena stressed that guaranteeing the protection of indigenous human rights should be a priority in the fight against climate change. Indigenous communities are disproportionately affected by the climate crisis, suffering displacement due to an increase in the number of environmental disasters that result from climate change—such as forest fires—and also due to an increase in the incidence of threats to their territories from illegal loggers during the Bolsonaro regime. Terena highlighted the injustice in the situation, stating that “with their day-to-day life practices, indigenous peoples already conserve the environment” yet they are among those who most suffer the consequences of climate change. She also argued that the displacement or immigration of indigenous communities to urban areas does not alleviate the group’s struggle. The environmental racism that indigenous people face when confronted with the climate crisis should be treated as location independent, since those within the urban context are also a marginalized group who have been disproportionately affected.

“There are over 350,000 indigenous people [living] in the urban context. They didn’t stop being who they are because they moved, they didn’t stop practicing their culture because they moved. They are who they are everywhere they go: in the village, in the city, abroad, in the courts.”

After Terena, Thais Santos shed light on the issue of environmental racism. As co-founder of the Quilombaque Cultural Community—a movement which addresses the problems and dilemmas faced by residents of peripheral areas through art, culture and knowledge—much of Santos’ speech focused on the way that environmental racism disproportionately affects quilombolas, who often live in rural areas with little access to modern technology [quilombos are communities of descendants of enslaved people in Brazil who still live on their ancestral lands]. Much like indigenous groups, Santos describes how quilombolas in Brazil “are invisible when we’re talking about the environment.”

Santos placed emphasis upon the climate crisis being a silent killer of minority groups. Traditional and direct violence against minorities are not the only mediums through which discrimination can occur: the climate crisis is now also a medium that enables the genocide of these groups. The WWF board member stated: “There is a large movement behind this because we are dying. When we speak about the genocide of black people, of native peoples, a lot are being killed, and not only with a bullet in the forehead. We are killed through the contamination of our water, contamination of our air, [by] putting pesticides in our food.”

Finally, Santos argued that the strategies for solving the climate crisis—such as the UN’s Conference of the Parties (COP) meetings—do little to address the actual problems that emerge as a result of the crisis. Governments and international climate summits are detached from the reality that those most in danger experience on a daily basis.

“The climate crisis is already internationalized, everybody knows we are living a crisis. It’s a giant risk, but we need to be there to protest. To show that the quilombolas are not living in the past, that indigenous villages are not living in the past. They are our present and they are our strategies for the future. Because if someone is going to manage to mitigate and handle this crisis, it’s not going to be at a COP with these people sitting around with pens in their hands and making decisions, not if they don’t have the humility to get down to the ground and ask in the villages, in the quilombos, and in the favelas: ‘How do you guys manage? What do we need to do with this soil? How do you plant?‘”

Similar ideas about the inefficiency of current solutions were echoed by Junior Aleixo. The climate justice specialist from AidAction Brazil criticized the use of carbon credit markets as a solution to the climate crisis. Aleixo condemned market interventions hidden behind the guise of global warming solutions, arguing that internal solutions from social movements within Brazil are more appropriate: “We [Brazil] are not the solution to the carbon credit market. We are much better than that. Our solutions, our social technologies are much better than the carbon credit market.”

The first panel concluded after 80 minutes, and the audience watched a short film by the Jacarezinho favela research and audiovisual laboratory, LabJaca, and the CIPÓ Platform. The film focused on climate justice from the perspective of various communities, with particular focus on sanitation and water security.

Demanding Racial and Climate Justice

For the second panel, three new guests were welcomed as the large crowd returned to their seats. Brazilian rapper, actor, author and social activist MV Bill was joined by indigenous climate activist and communicator Lídia Guajajara, as well human rights activist Lúcia Xavier to discuss the lecture topic of Racial and Climate Justice.

In a similar vein to Eloy Terena in the first lecture, Lídia Guajajara emphasized the importance of acknowledging the struggles of Brazil’s indigenous population with regard to climate justice. The Mídia Índia and ANMIGA communicator argued that failing to recognize this is, itself, a reflection of climate injustice: “climate injustice is precisely that—not recognizing the struggle of the indigenous peoples.”

Guajajara added that environmental conversations about the Amazon must not overlook the struggles of indigenous communities because the two are not mutually exclusive, but rather intricately intertwined: “One cannot think of a living Amazon, a living environment, without thinking of the struggle of the indigenous peoples.” It is impracticable to have a conversation about the physical environment without the communities who live and are connected to that environment.

MV Bill—who grew up in the City of God favela in Rio’s West Zone—agreed with Guajajara that conversations about the environment must include the humans who live in those spaces:

“I could never think of disassociating human beings and the environment. I always thought that by having more educated, better prepared, better informed, more evolved people… of course we could have a population more involved in [preventing] the deterioration of the environment.”

The influential rapper who has over one million monthly Spotify listeners, discussed environmental racism and how it affects the majority black population in Brazil’s poorest and most marginalized communities. Many favelas have suffered from the climate crisis as a consequence of unequal access to resources, with polluted rivers, lack of sanitation and poor access to safe drinking water just a few examples of the environmental racism that favela residents face.

Recalling a visit to a quilombola community in Bahia, MV Bill highlighted how these communities suffer the effects of environmental racism at the hands of government officials who could help, but choose not to. He stated that “those who could help preserve, actually want to destroy and build.”

Lúcia Xavier questioned whether governments will ever deliver on their promises to protect the most vulnerable. Considering the exclusion of those threatened by decision-making processes, the human rights lawyer argued that changes are happening so slowly that the groups desperately fighting for improvements may not even be alive to see public promises fulfilled:

“I imagine that there won’t be visible changes if black people, if indigenous people, if other social groups can’t participate… can’t decide. Why discuss? We are already discussing, but if we cannot decide, we can forget it, understand? Half of us will be gone at some point. We won’t ever have access to that transportation, to live on the land [that they have promised].”

The event finished on a poignant note where—at a venue that has witnessed performances from many of the world’s most acclaimed musicians—MV Bill rose to his feet to deliver a poetic, a cappella rap that reflected the common experience shared by many Brazilians whose needs have too often been ignored by those in power. As Brazil prepares to embark on a new journey with a new leader at the helm, the Climate of Change event serves as a reminder that the issue of climate justice must rise to the forefront of the country’s attention, and be treated with the urgency that is required.