On June 17, 2023, Rio de Janeiro’s Sustainable Favela Network (SFN)* launched its Favela Climate Memory Exhibition, the culmination of five day-long climate memory circles held by favela community museums between January and March. This series of articles explores the dynamics of each memory circle which makes up the exhibition, with this article introducing the third discussion circle, held on February 11 by the Historic Orientation and Research Nucleus of Santa Cruz (NOPH) in Antares. Developed by the SFN’s Culture and Memory Working Group, the project was realized by community museums, technical allies, and community organizers from favelas across Greater Rio.

The Sustainable Favela Network’s Climate Memory Circles are community events aimed at recovering and recording the memories and stories of long-time residents of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas in relation to the environment so as to envision ways to prepare for climate changes to come. Though still rarely discussed, the memory circles showed that climate change is very much present in the daily lives and concerns of favela residents.

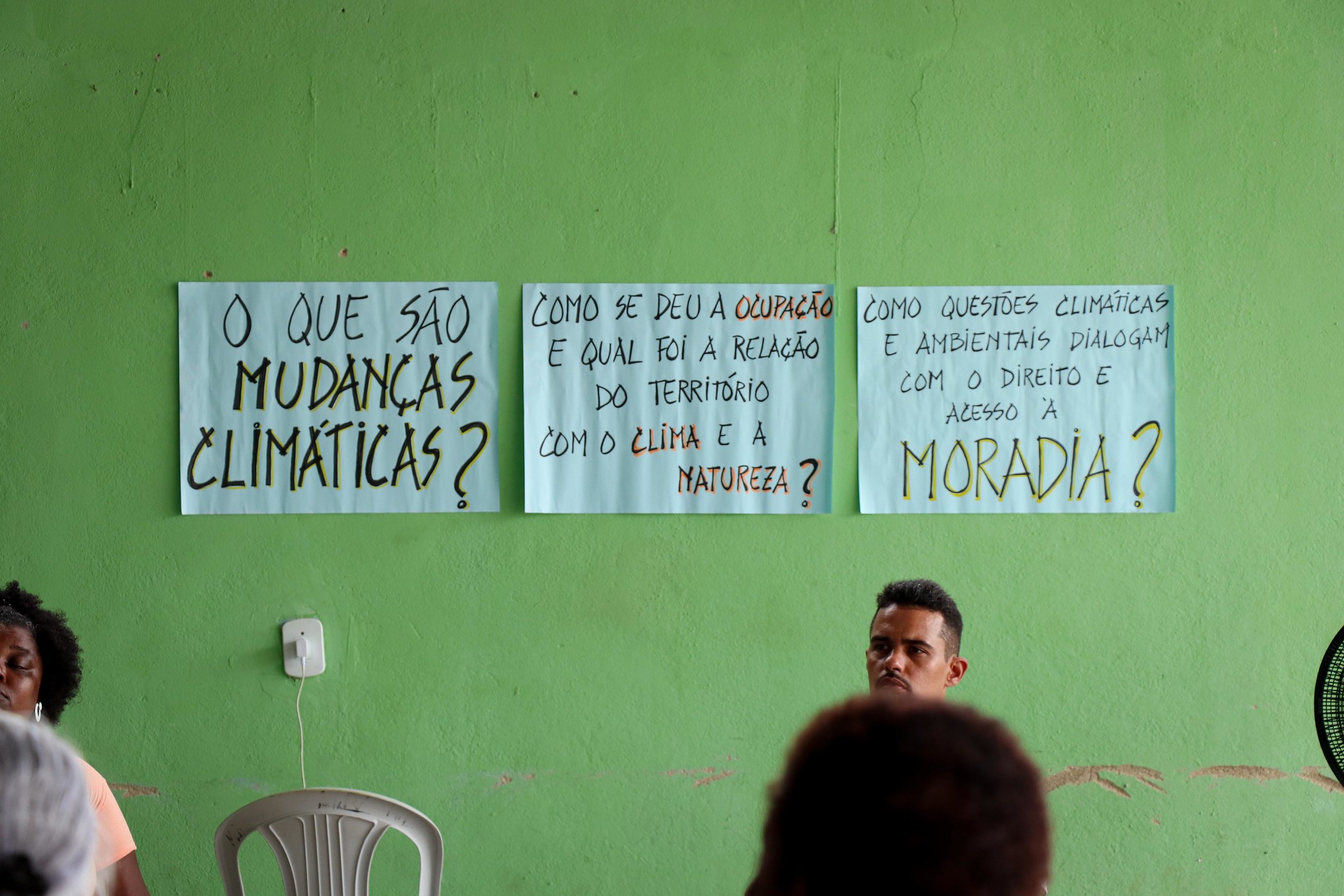

Each memory circle event took place over the course of a day, with residents invited by the museums to take part in a series of discussions designed to focus on and dig deeper into the climate change theme. Residents shared their views and experiences of climate change, recovered memories about the settling of their communities and the relationship of this settlement period with the surrounding environment, discussed the relationship between climate impacts and housing rights, and explored solutions and organizing by residents, highlighting the mistaken priorities of the State, which tends to see forced evictions as the solution.

The third Climate Memory Circle took place on February 11, 2023, organized by the Historic Orientation and Research Nucleus of Santa Cruz (NOPH) in Antares, in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone.

The discussion circles were held in a space that used to be a community daycare, Sonhar Conceição, and were attended by mostly older residents and community organizers. This gave a special quality to the way issues were discussed, as the main objective was to remember and record the relationship between the favela, its origins, and the natural environment, as well as socio-environmental changes that have occurred since the community was founded.

The event was hosted by Leonardo Ribeiro de Sousa, a member of NOPH, historian, and resident born in Antares. He opened the event with a short introduction and highlighted the long struggles over years in the community, be they through institutions or the children and grandchildren of residents, and that this was a day to present these and so many other questions, memories, and tensions.

What Does Climate Change Mean to You and to Your Community?

Opening the first discussion circle with the question “What is climate change to you?”, NOPH coordinator Bruno Almeida introduced himself and reflected on the importance of speaking about Santa Cruz’s history.

“Normally, we talk about other aspects of [Santa Cruz’s] history. A history connected to the presence of Jesuits, to the emperor’s summer homes, and sometimes we forget the stories of other places here in the Santa Cruz neighborhood [beyond the Imperial Way, a 17th and 18th century road connecting Rio to the surrounding countryside]. So, recently we have begun studying the origins of sub-neighborhoods and communities, João 23, Cesarão, etc. [It is important to] understand the place we inhabit, not only in order to overcome prejudices, but to propose improvements. If we know a place’s roots and the history that has brought us here today, we can better prepare ourselves so as to try out improvements. One such improvement is this discussion circle with residents of Antares, so that we can have a conversation centered on the issue of climate change.” — Bruno Almeida

Participants began their statements making clear that many of them have lived in the area for a long time and their lives have been marked by climate events. Sandra Regina de Oliveira, a resident of Travessa for 58 years, experienced a flood she has never forgotten in which she lost everything. Another resident, Vera Lucia Rodrigues, reported a similar and repeated experience. Her family arrived in Vila Verde, a precarious and swampy area, in 1985 and has lost everything more than once during floods in the region.

“I’ve suffered lots of floods, I lost everything. But here I am, on my feet, fighting again. Warriors don’t die… warriors live!” — Vera Lucia Rodrigues

The memory of destructive weather events permeated many subsequent talks, such as one given by Leny Martins, 61, who arrived in Antares when she was 16 years old. Despite the difficulties she has faced, she reaffirms her love for the community.

“I have suffered so much in this place. I lost everything in my home in a flood. There was no water, no electricity… but I love Antares very much.” — Leny Martins

Eufrosina Silva, known as Dona Flor, was one of the residents present who’s lived in Antares the longest. She was thankful for the opportunity to speak of her relationship with the community.

“I am 81 and have lived here for 45 years. The struggle was huge. I worked in the residents association. Then I studied at night to be a preschool teacher. Thank God I worked at the daycare for 25 years over in Santa Cruz. I would leave at midday and work with the elderly until five in the afternoon. I worked a lot and now I’m resting. But I’m alive. I am here among you all and I am present. And Antares has a lot to do.” — Eufrosina Silva

Dona Flor demonstrated the way in which the community takes action locally, describing how she and other residents resolved the lack of water in the region.

“I went hungry. We had no water. We had no water in the tap. We made our demands and managed to get water. We got electricity. We achieve things through our struggle. We won’t get anything if we just stand still!” — Eufrosina Silva

Resident Carmem Lúcia recounted how she first came to the community and fell in love with it.

“I came here in 1976 to work in the school… Antares was the star that changed my life. I am in love with Antares. It was here that I went back to studying. I liked the school and kept working. And when the religious community came, we built the first bridge between the communities. I’m retired, but I’ve come to help with whatever’s needed in the community.” — Carmem Lúcia

Another resident, Rosimar Paixão, recalled what it was like arriving in Antares in the 1970s when there was no infrastructure, and told the history of the community’s fight for improvements. For her, the locality was a pillar, a place that served as a guide and in which she made many friends over decades.

“I came to Antares very young, in 1975. Your friendship is essential in my life… Ours was a very tough childhood… There was no electricity, no water, we had dirt roads… I love my community and everything I can do for it I will do. I have built a very good coexistence with my community. I want the community by my side and, together, we will grow. Between 1975 and now, we have had many losses. No matter the [public] management, we residents always lose. We can only make it if we work together. We are a family! We have so much strength. We only need to know how to use it.” — Rosimar Paixão

How Did the Occupation of the Favela Happen and What is the Area’s Relationship With the Climate and Nature?

Climate events were a clear theme in many residents’ talks, with mentions of floods and their consequences in the history of the community and the relationship between this history and their own lives and families. In the second circle, those present were asked how the occupation of Antares came about and what was the area’s relationship to the climate and nature. Leonardo Ribeiro contextualized that Antares grew as a result of forced evictions in other parts of the city, mainly the South and North Zones—a common feature in the history of large favelas in the West Zone. Many older residents were not born in Antares, but helped found the community and are parents and grandparents to people born and raised there.

Ribeiro’s mother, Maria José, explained that she and her family used to live in Morro dos Macacos, in Tijuca. Evicted from Morro dos Macacos, they went to Complexo da Maré, where they were also removed and sent to Antares. Other residents present in the circle share a similar experience, including Iolanda da Silva, who arrived in Antares approximately 50 years ago from Rocinha.

“Pantanal [a neighborhood in Antares ] was abandoned, it was all forest and ditches. Today, everything there is paved. But I’ve seen a lot of change. I remember the flood that carried the bridge away with everything. But I believe there should be more improvements, more projects for the community. The youth have no prospects.” — Iolanda da Silva

As Ribeiro explained, the term “Pantanal,” or wetland, is not coincidental but is intimately bound to the local history of Santa Cruz.

“The Antares community is in an area which is historically a water basin and always flooded. Most of the canals in Santa Cruz today were built by Jesuit priests when they occupied the neighborhood. They made plantations, but would end up losing them to floods. Then, they built the canals with the labor of enslaved people. The priests made the plans and Black enslaved people built them.” — Leonardo Ribeiro

How do Climate and Environmental Issues Dialogue with Housing Rights and Access?

The explanation reminded Leny Martins of a dramatic situation during a flood in Antares, a situation that relates to another of the circle’s guiding questions: how climate change and environmental issues dialogue with housing rights and access. Like Martins, many residents have experienced the trauma associated with increasingly frequent extreme weather events.

“At the time, my grandson was eight years old. I grabbed him and took off, but the water was so intense, it really came in strong. He tripped and let go of my hand. I started screaming: ‘My grandson! My grandson!’ And then a young man came and grabbed him by the foot from inside a large hole they’d made in the street. Where I live, any light rain causes flooding. The house floods, everything floods. It’s horrible! There is no outflow, so when the river fills up, it overflows. Water comes in from the toilet, from the sewer, it comes in from everywhere. There is no way out. It takes over. I lost everything, fridge, television, sofa. Twice this flooding happened. I got scared. Guys, will it flood again? Will I lose everything again? My heart races when it starts raining, I get scared.” — Leny Martins

Carmem Lúcia told of how Santa Cruz, an essentially agricultural region, was urbanized. Sandra Regina de Oliveira recounted the occupation and Leny Martins specifically recalled the occupation along the railway line: “There by the train line was pure trash. Now that people have occupied [the area] there is no trash.” This complex relationship with waste emerged as one of the main discussion points. The region was occupied by way of the government evicting people in other regions and resettling them in Antares. In practice the resettlement occurred informally with little to no urban planning, including solid waste management. This abandonment reflects systematic government neglect in relation to the favelas.

“The garbage issue in the community is a problem. There was no construction at the time, there weren’t even trees. Where did sewage from the houses go? Everything [went] into the creek behind the hill. I used to go fishing back there. These days, you don’t fish anymore, there’s only trash. And this creates what? In summer, fires, wildfires… because all sorts of things get dumped there. I think the community needs to have more awareness around this. You want to build? Find the best way, the best project and [work out] where the sewage goes. If we don’t work on preservation, the government will come and say ‘they [residents] don’t care, so why should we ?’” — Rosimar Paixão

On the same theme, other residents and leaders felt there are other urgent issues to be resolved, such as the impact of cooking oil being disposed in the favela’s improvised and inadequate sewerage system.

“One of the problems I have identified is the oil in the sewerage. People fry things and throw [oil] down the sink. When it gets to the sewer, it’s cold. It turns [solid] in there and clogs the sewer… The biggest sewerage issue we have in the community of Antares is oil.” — Leonardo Ribeiro

Ribeiro also stated that Antares has lost its trees over time, an occurrence influenced by families’ need for housing.

Resident Vera Lúcia recalled that Antares was settled under the influence of City Hall, but it was supposed to be, at least in theory, only for the screening of families evicted from other places. “Antares was [supposed to be] temporary housing. They put people here in tiny little houses. There was a fence, you couldn’t do anything… No one was supposed to stay here. Forty years went by. They didn’t take action.”

“It’s very easy to blame the Antares community for floods. But people here are always focused on what’s best for the community. The issue here is education, leisure, sports. I know I’ve done my part… We need to make a greater effort here in the community for people to understand that they need to look toward tomorrow and for everyone.” — Sérgio Sodré

What Knowledge Has the Community Already Developed to Respond to the Challenges Posed by Nature and Climate Change?

Ribeiro closed the discussion circle commenting that there was a City Hall project in the early 1990s for community street-cleaners coming from the favelas themselves. “They were the ones who worked on raising awareness. But the residents associations started being stigmatized for involvement with parallel powers [drug trafficking gangs]. And they were harmed. And we suffered more during that time,” he remembered.

However, according to Ribeiro, conversations and sharing are indispensable, even if they only lead to victories many consider small. He recalled going to a Santa Cruz Security Council meeting with municipal and public security representatives to discuss the dangers of police operations during times when students arrive at and leave school. “It was a solution we really worked on and pushed hard. Dialogue between a favela and the local police station is a taboo subject. And do you know what the result was? The station became a community library. The space was donated based on the relationship established with the police,” he recounted. The dialogue helped ease tensions between the community and police—a lesson that could be applied to other issues.

Read the entire series of reports on the Favela Climate Memory project.

Don’t miss the album below (or click here to view on Flickr):

*The Sustainable Favela Network (SFN) and RioOnWatch are projects of Catalytic Communities (CatComm)