On June 17, 2023, Rio de Janeiro’s Sustainable Favela Network (SFN)* launched its Favela Climate Memory Exhibition, the culmination of five day-long climate memory circles held by favela community museums between January and March. This series of articles explores the dynamics of each memory circle which makes up the exhibition, with this article introducing the second discussion circle, held on February 4 by the Sankofa Museum in Rocinha. Developed by the SFN’s Culture and Memory Working Group, the project was realized by community museums, technical allies, and community organizers from favelas across Greater Rio.

The Sustainable Favela Network’s Climate Memory Circles are community events aimed at recovering and recording the memories and stories of long-time residents of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas in relation to the environment so as to envision ways to prepare for climate changes to come. Though still rarely discussed, the memory circles showed that climate change is very much present in the daily lives and concerns of favela residents.

Each memory circle event took place over the course of a day, with residents invited by the museums to take part in a series of discussions designed to focus on and dig deeper into the climate change theme. Residents shared their views and experiences of climate change, recovered memories about the settling of their communities and the relationship of this settlement period with the surrounding environment, discussed the relationship between climate impacts and housing rights, and explored solutions and organizing by residents, highlighting the mistaken priorities of the State, which tends to see forced evictions as the solution.

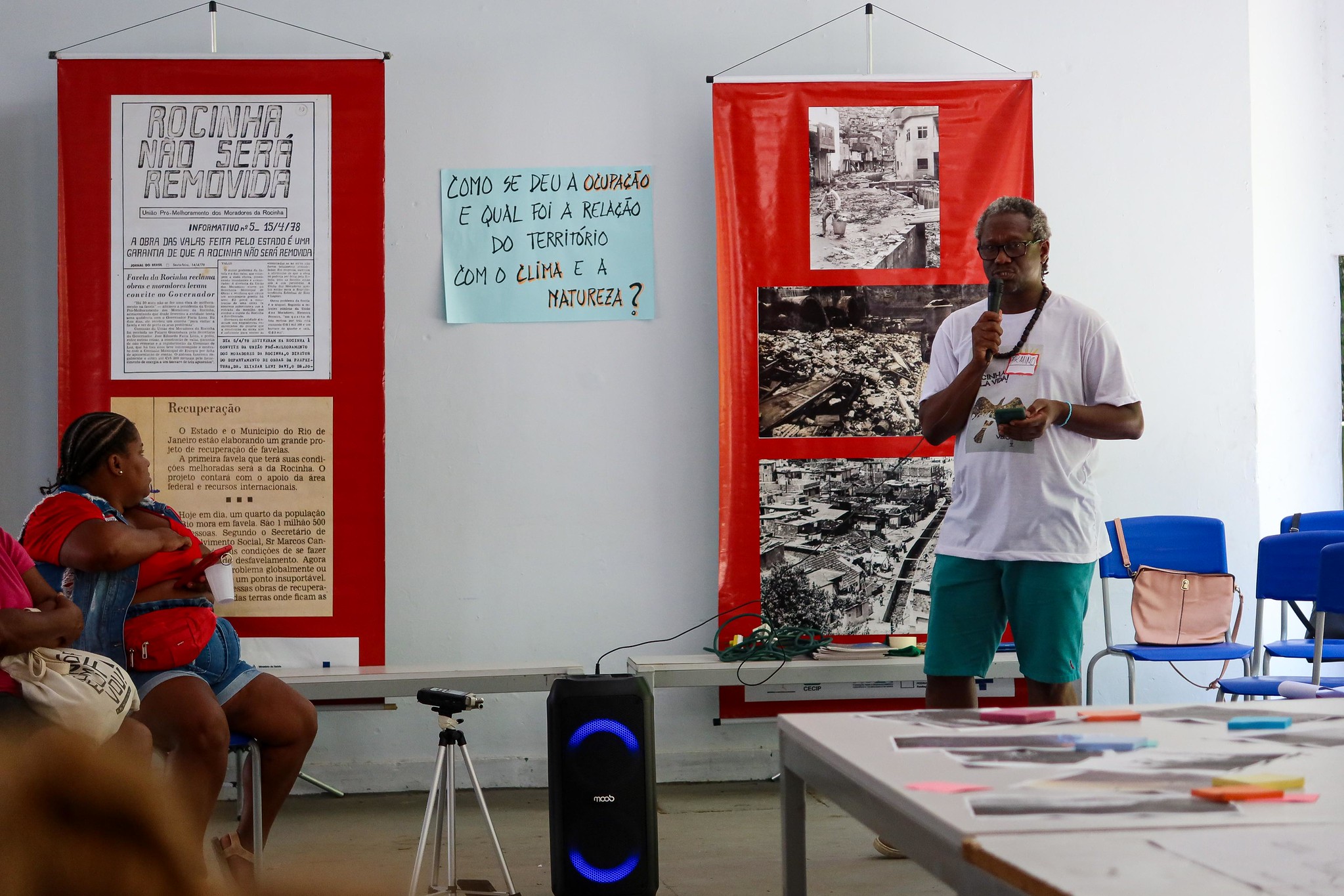

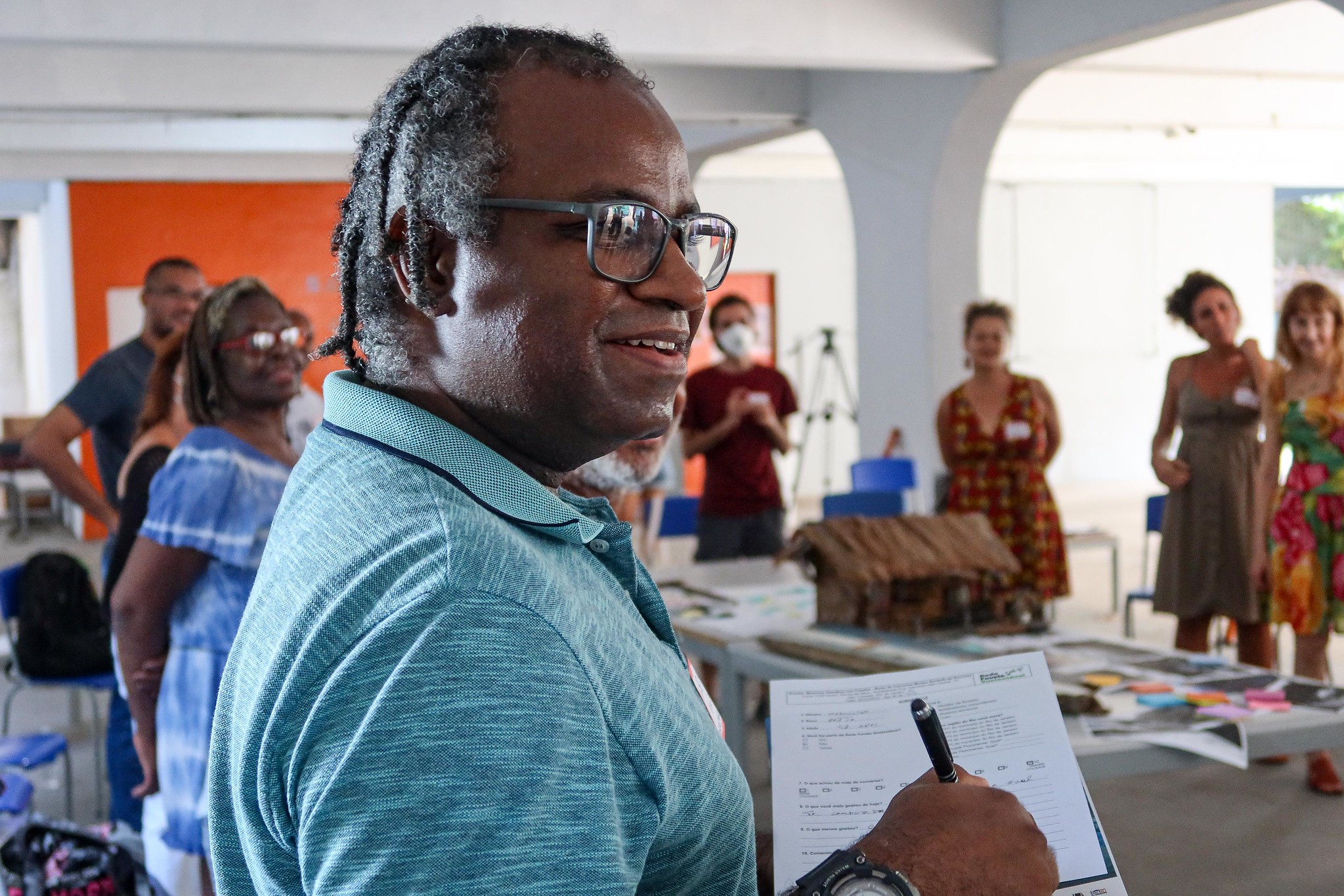

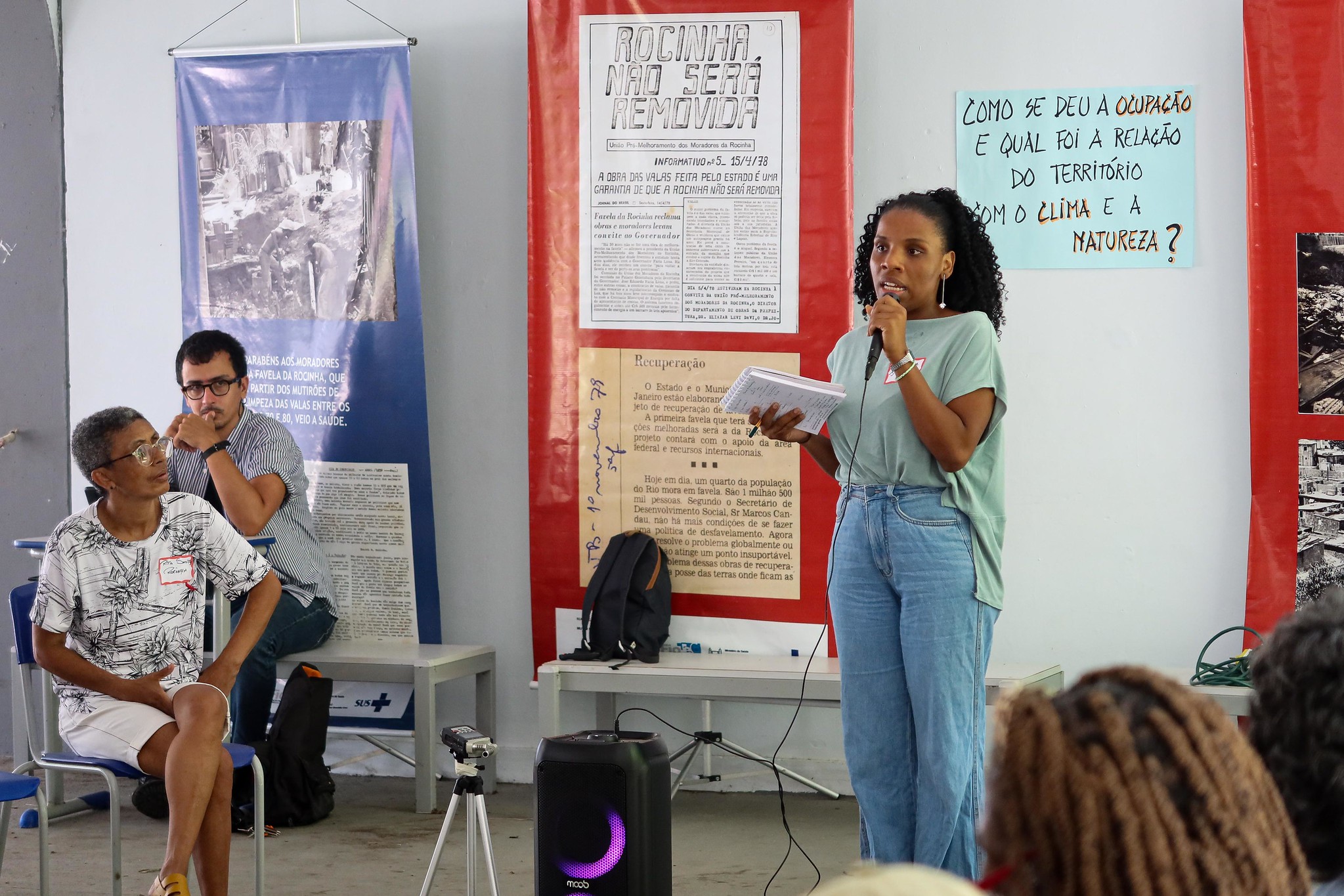

On February 4, 2023, the second circle of the series took place: the Rocinha Climate Memory Circle held by the Sankofa Museum at the CIEP Ayrton Senna state public school. Over a full Saturday, members of the museum led very rich discussions with 50 residents and activists from Rocinha, young and old, along with collaborators and friends from other participating museums.

First to speak was host and organizer of the meeting, co-founder of the Sankofa Museum, Antonio Firmino. A resident of Rocinha for 30 years, Firmino began the day by introducing the history and development of Rocinha, and the museum which was created in 2008. He described how the museum’s roots go back further, however, starting decades earlier with the work of Lygia Segala, an anthropologist who ran a literacy project in Rocinha in the 1970s. She encouraged students to collect stories and testimonials from residents, with help from Antônio Oliveira, president of the Union for the Improvement of Rocinha Residents (UPMMR), and Tânia Regina da Silva, another local leader.

What Is Climate Change?

The first discussion circle of the day explored the community’s relationship with climate change. Magda Gomes, 28, a resident of the Trampolim area in Rocinha, recalled the torrential rains of 2019 which caused a landslide in Laboriaux, an area high up in the favela. She shared that “we gathered like this in an emergency situation… Unfortunately we [always] gather to debate climate change and urgency from the perspective of loss and damage.” Gomes reported her sadness at the “absence of public policies that understand that discussing climate change and emergencies means above all discussing quality of life and future generations.”

Maria Helena Carneiro de Carvalho, a decades-long resident of the Rua Dois area, commented that she remembers her childhood in the forest with waterfalls throughout the community that are now hidden by buildings and alleys. She called for collective action from the community, including the involvement of nearby neighborhoods.

“Rocinha has yet another serious problem because it’s on the edge of the Tijuca Forest. We are destroying our city’s green lungs. Our lungs. We are totally destroying Rocinha. And so [it’s like] you haven’t breathed for a long time, the air hasn’t circulated for a long time, and it just gets worse and worse.” — Maria Helena Carneiro de Carvalho

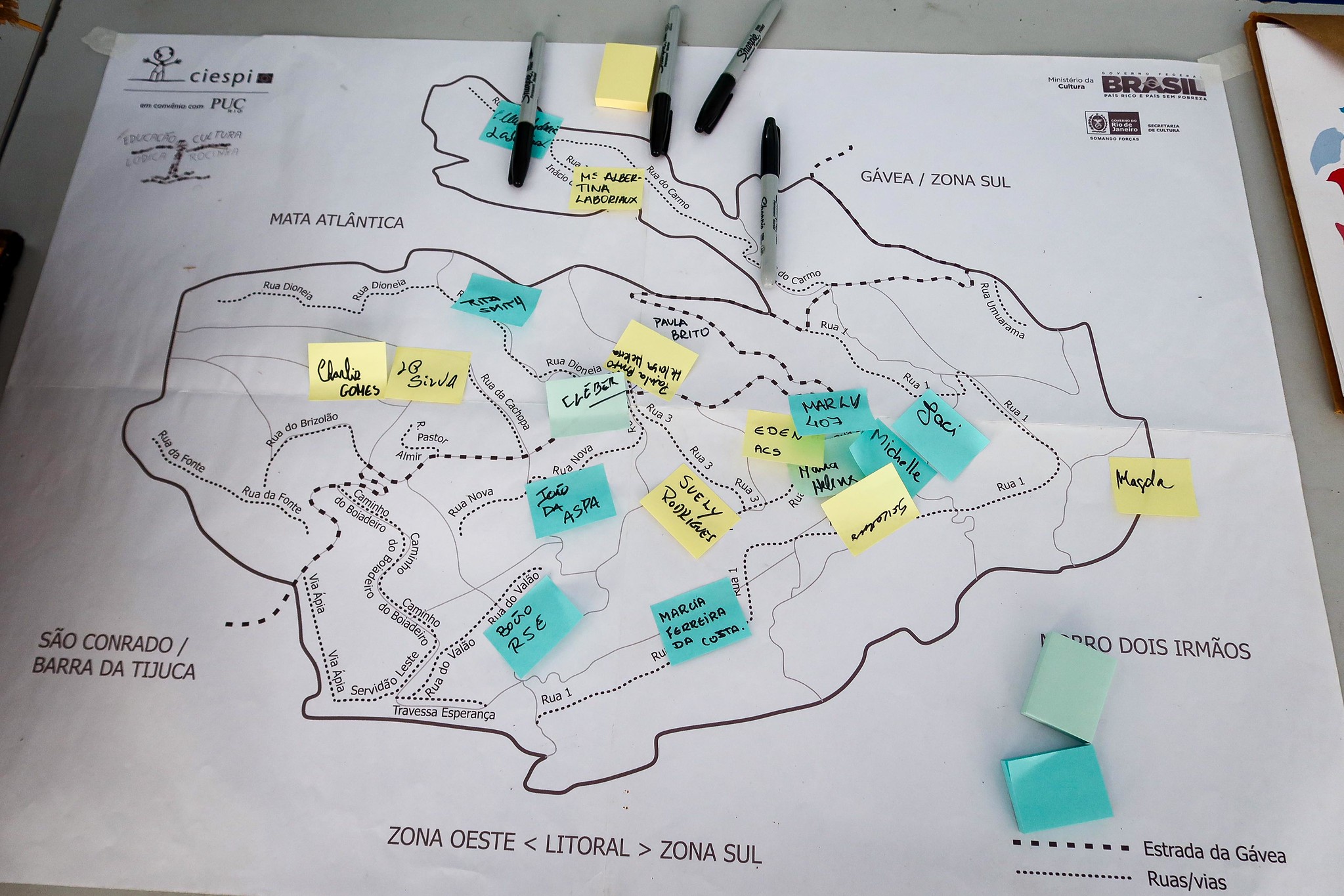

Rocinha is so large that some of those present proposed discussing and understanding the specific realities of each area, of each sub-neighborhood that makes up the favela, since they are very distinct.

“We don’t say ‘the Rocinha favela’ because it’s too big. I say ‘Rocinhas’ because both the occupation and public policies affect residents in different ways. Those living in Bairro Barcelos, a more upgraded area, have different living conditions to those living in Macega or Roupa Suja. It is important to specify and consider the reality of each neighborhood.” — Izabel Carvalho

Leandro de Castro, an activist from Rocinha Resists, shared his opinion that Rocinha is now at a limit, meaning that residents’ search for secure housing may have reached a situation which may cause imminent risks.

“We now live in a city where concrete has taken the place of the forest. Rocinha used to be a place for working-class people who wanted to live closer to work. But now Rocinha is at its limit… We already know what people [unaware of local struggles] would say. This movement [of the community trying to preserve itself] has a long history. Rocinha Without Borders does that, with community clean-ups and all that… [But] we’ve reached the density limit. Nature has given us and will continue to give us its response. During the summer, I get scared when the sky goes dark in the late afternoon. Really scared. I worry because we are witnessing a State that has created an exclusively reactive system [not preventative]. I don’t want them to only show up when Laboriaux collapses. Or Dionéia. This is the moment for us to make a statement that Rocinha is at its limit. When nature does respond, it will be chaos. I hope that we can organize ourselves before that happens.” — Leandro de Castro

Memories of heavy rains ended up being the main theme related to climate memory in the discussion. Some recalled the terror felt when hearing the siren warning of landslide risk. Others have experienced extensive material losses, and others reported learning from their parents that they were born in the middle of a flood.

How did the Occupation of the Favela Happen? What is the Area’s Relationship with the Climate and Nature? How do Climate and Environmental Issues Dialogue with Housing Rights and Access?

The introduction to the event’s second session, which was coupled with the third, dealt with how the community was originally occupied, its relationship with nature, and the connection with housing rights. Firmino highlighted that the session followed the same methodology that has always been used in the occupation of Rocinha: collectivity. He also took the opportunity to explain to those present why he defends the use of the terms favela and favelado (favela resident), rejecting euphemisms that he believes erase these spaces and their historic struggle for housing.

“I am a favela resident, a favelado. [The term] community was introduced at the same time as the [Pacifying Police Units] UPPs, coming in from the outside. All of us who live in favelas have always been communities because the fight for the common good is about being a community! Favelas continue! From my point of view I am a favela resident because it [favela] has a whole meaning of struggle and resistance. I was denied the right to housing!” — Antônio Firmino

Resident Rita Smith was visibly agitated when responding to the question of the community’s occupation and how it relates to housing rights.

“We forget one word. Life! How many people have we lost? We created access to housing without any guidance, often without even technical guidance.” — Rita Smith

Others emphasized land management issues and their relationship with identity and belonging as the foundation of Rocinha’s most pressing problems.

“What do we as favela residents want? Our house. And what is that? Our identity. And it has to be documented, doesn’t it? You can live on the asphalt [formal city], but what we want is our identity. And our identity is here. When we are born we come with an identity that becomes a certificate. And the certification we want is land titling.” — Maria Helena Carneiro de Carvalho

In the early 1980s, Rocinha residents organized to demand basic sanitation systems, urban intervention for adequate housing, especially for families who suffered with flooding, and to reject compulsory forced evictions. Long-time community leader, Antonio Xaolin, shared this story with participants.

“In the early 1980s, they wanted to remove Rocinha and Vidigal. We started a fight along with the Bento Rubião Foundation… And the Catholic Church joined the fight… From the moment the Pope went up to Vidigal, the specter of forced evictions diminished.” — Antonio Xaolin

Xaolin continued, expanding on the importance of residents’ continued and united struggle to secure their rights.

“What we are doing here is an exchange of knowledge. Internal political disputes exist. They will always exist. [But] when the collective decides to fight together, the collective wins. We stopped the removal of Rocinha. We succeeded in getting health services. We got the state public school and the subway through collective struggle. We practically had a class struggle. It was a finger in the face of the elite… Rocinha has collective wisdom.” — Antonio Xaolin

This perspective is needed since outside agents have a historically hostile view of the favelas, which persists to this day. Firmino pointed out that certain horizons never seem to widen.

“It seems like all of us favela residents live in another country. We’re always at war. Why does the Brazilian government say it is going to ‘reclaim territory’? The state always treats us like this… it’s like we’re a different country.” — Antônio Firmino

Returning to the theme of housing, one of the oldest residents in the circle testified to often ignored structural changes that have a huge impact on local resilience. Growth of the rental market means residents invest less in their homes and surrounding communities and lose a sense of belonging—a vital tool in caring for a space.

“Twenty years ago, growth was horizontal and deforested little. Now it’s horizontal and vertical. Lots of buildings have gone up and turned [Rocinha] into one of the places with the most renters… in our city.

How does this affect the climate? Before residents were homeowners and considered themselves caretakers of the space around their homes. Renting takes away this responsibility. A landlord who owns a lot of property isn’t going to be concerned with the area around that one house. He’s [only] bothered about the rent.” — Ulisses José da Silva

Civilian firefighter Ricardo Ramos went further into the current housing situation in the community.

“Someone [from outside the favela] comes with money and buys a two-story building and adds on four more. They don’t have to pay water and city taxes. And we, the people from here who have never done that kind of thing, are now here trying to solve this situation, which we have to do with tremendous caution… The reality is that they [government and outside landlords] don’t give a damn about us.” — Ricardo Ramos

Shortly after, community leader Mauricio Fagundes da Silva, known as “Soca,” reiterated that time is running out and conditions have changed with increasing climate vulnerabilities as Rocinha continues excessive consolidation.

“We can’t solve things in meetings like this anymore. Why? Because administrations come and go and they’re never bothered about us. If we don’t wake up and get our foot in the door to solve this impending tragedy, Cachopa and Dionéia [areas in Rocinha] will collapse. There’s a lot of weight in that area. People dig away, but never reach the rock. Nature’s time is not our time. Future generations will suffer. We have to take a stand.” — Mauricio Fagundes da Silva

What Knowledge Has the Community Already Developed to Respond to the Challenges Posed by Nature and Climate Change?

As Antônio Firmino told RioOnWatch in 2016, presenting historical documents to younger residents shows them that “what you have today is the result of past struggles.” The Sankofa Museum operates with the deliberate intention of building a bridge connecting the past to the present. The name Sankofa comes from the Adinkra symbol of the West African Akan people and means a return to the past to understand the present and transform the future.

Around the discussion circle, some Sankofa Museum posters showcased communal collective actions over time, such as the joint cleaning of ditches and gutters. Others captured the lived memories of participants who helped control some of Rocinha’s significant sanitary problems and were essential during discussions with public authorities coming into the neighborhood.

The images were ideal for illustrating the final circle discussion, which focused on remembering solutions developed historically by the community. Fernando C.F., a 63-year-old resident of Rua 3, shared his experience.

“Nowadays, I thank God I have my water. From the spring itself, potable. We started by laying down the pipes, and then we added concrete. In the old days we didn’t have that.” — Fernando C.F.

Rose Firmino, member of the Sankofa Museum and facilitator of the final circle discussion, questioned the conventional wisdom regarding where solutions for society at large might come from.

“I can have a sustainable house that adapts to climate change and yes, I can look for a support system and be happy [in the favela]. And I believe that we favela residents are not lesser than anyone else. On the contrary, our knowledge makes and has made all the difference. We Blacks and favela residents have lost touch with our sense of ourselves as creators of a community, of being a quilombo.” — Rose Firmino

Regarding the search for concrete, structural solutions, Magda Gomes spoke again.

“This is a social problem with a beginning, middle, and end. We need to exchange ideas, projects, and investments… We need an intersectional approach among all stakeholders and arrive at this place we are rehearsing here. To transform Rocinha into a healthy, dignified place, where a person can breathe. It’s the right to my life.” — Magda Gomes

Read the entire series of reports on the Favela Climate Memory project.

Don’t miss the album below (or click here to view on Flickr):

*The Sustainable Favela Network (SFN) and RioOnWatch are projects of Catalytic Communities (CatComm)