At the Firjan SESI Theater, located in downtown Rio de Janeiro, I had the opportunity to watch one of the final performances in the recent run of Monkeys, a monologue written and performed by multi-award-winning actor and playwright Clayton Nascimento. The play addresses the urgent fight for Black Brazilian lives against the normalization of police brutality, genocide of Black youth, and the agony of mothers who lose children to State violence. Prejudice against Black people sets the tone for the whole piece, starting with the play’s title; in line with the arguments of influential Brazilian anthropologist Lélia Gonzalez, Nascimento subverts the racist slur “monkey” to reclaim it based on the narrative and perspective of Black people. According to Gonzalez, beyond resistance there is subversion. She proposed a discursive battle to subvert language, one of the most effective colonial tools in the process of subjugating Black bodies. In this context, Nascimento places the subversion of structural racism right at the center of Monkeys, from the title through to the final curtain.

The audience at the performance was majority white. For the few Black people in attendance, the actor’s words recalled very familiar and intimately felt pain. I noticed that the play had already started for me even before the actor took the stage. The audience’s energy ran through me. As Nascimento stood on stage, he worked to organize and channel this energy, transforming it into art. And he does this exceptionally well.

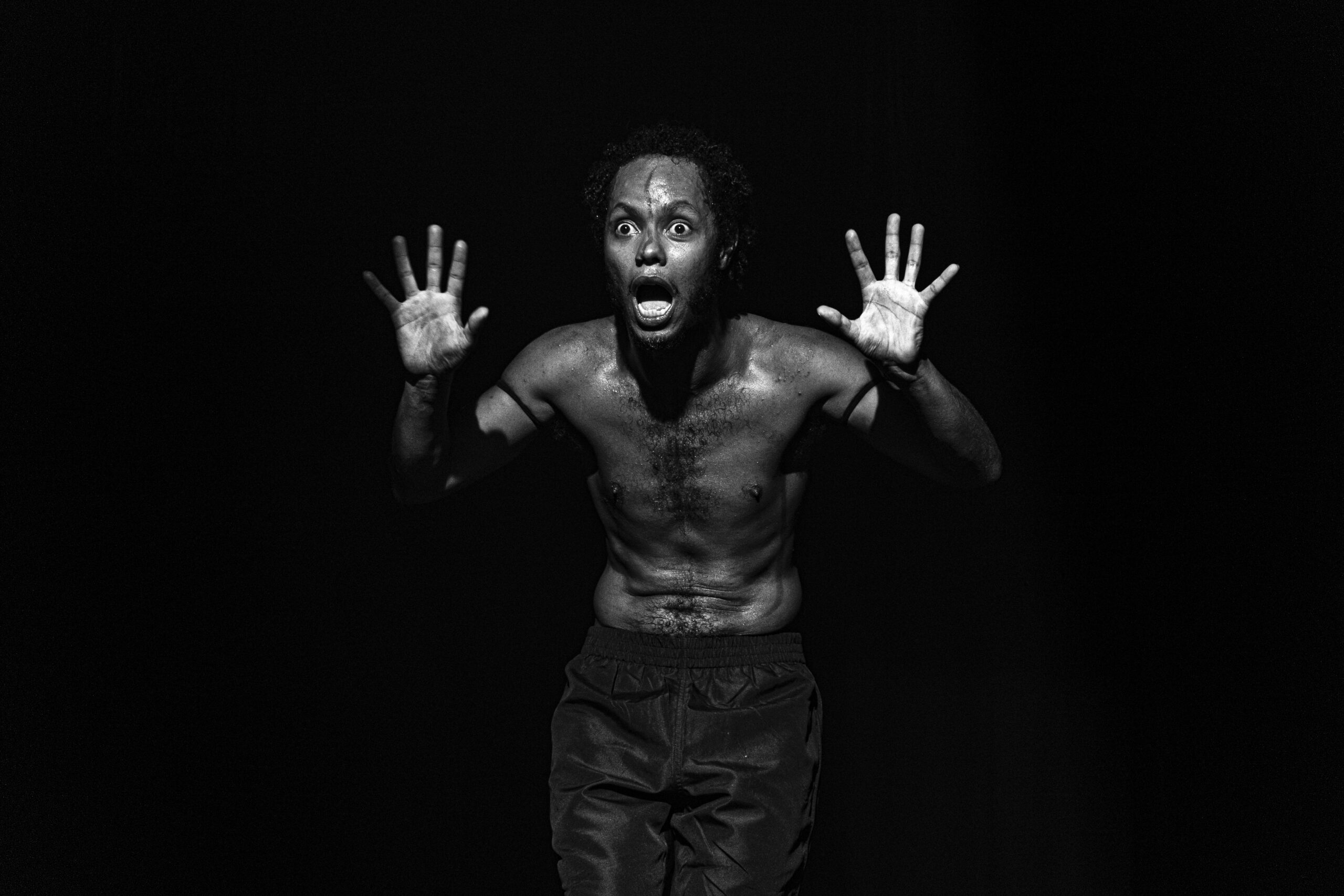

The bell sounds for the third time. The monologue begins with a powerful scream: “MON KEYS!” This instantly intensifies the atmosphere onstage. The actor goes on to yell repeatedly, “Monkeys! Monkeys!” filling the stage devoid of scenery or furniture. Alongside the screams and acting, the scene is enhanced by lighting effects and a subtle mist hovering over the theater. Nascimento performs in the same costume throughout the play: his Black body wearing black bermuda shorts with a red lipstick in his pocket. Incredibly, the lipstick is used in the second act to create a historical map explaining the colonization of Brazil.

I witnessed how Nascimento commits to and throws himself into the sensitive narrative that follows. It is a phenomenal monologue performed by an artist who is strong, prepared, and committed to the role. It is no surprise that Nascimento is one of the youngest actors to receive two best actor awards this year: the 2023 Shell Best Actor Award and the 2023 APCA Best Actor Award.

View this post on Instagram

Monkeys deals with intense and sensitive themes, expanding the audience’s perspective on the reality faced by mothers who lose children to police violence during police operations in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas. Nascimento has the skill of inhabiting various characters during the play, embracing the journey of different Black personas. By embodying diverse characters, he deepens the audience’s understanding of a cruel and delicate reality.

The narrative brings discomfort to the whole audience, and leaves the few Black people present in tears. We are on the edge of our seats from the very start. One of the characters Nascimento brings to life is Eduardo de Jesus Ferreira, a ten-year-old boy killed in Complexo do Alemão in Rio’s North Zone in 2015. On April 2, 2015, community media reported that the boy Eduardo was killed during a police operation. His mother was in the kitchen as her son played by the front door when she heard shots fired. She ran to him and found him dead from a shot to the head fired by the Military Police.

Focusing on the journeys of real characters, the play delves deeply into themes such as the genocide of the Black population, and deconstructs historical myths of Brazilian racism. The actor also employs satire to alleviate the play’s intensity. However, the work consistently points towards the necessity of discomfort and reflection on racial and social issues to one day overcome them.

The monologue provides a mature and uncompromising look at the situation of Black Brazilian theater. However, it is essential that Black people approach the narrative with caution as it can be triggering and cause much discomfort.

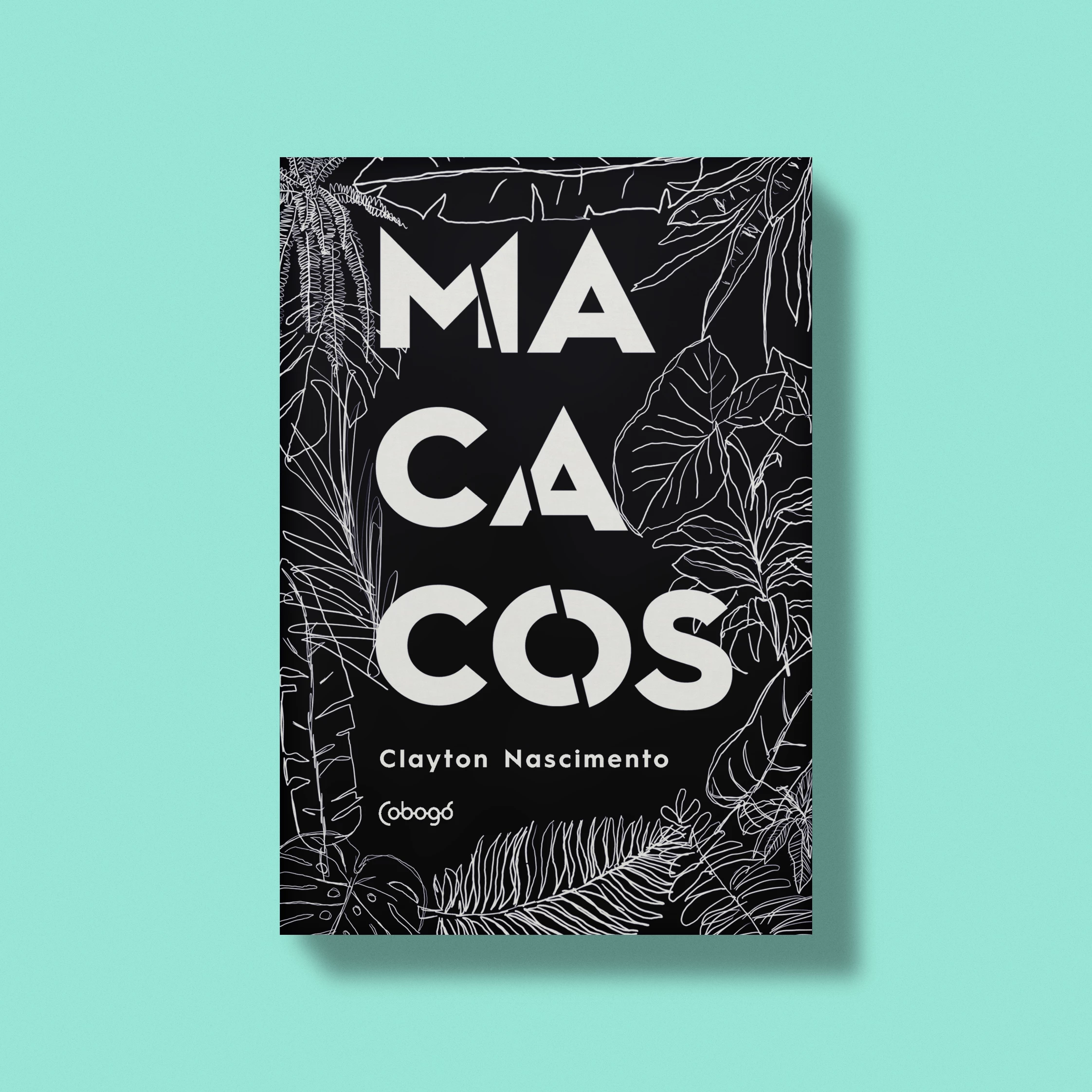

The current run of Macacos in Rio de Janeiro has ended for now, but the work is available in Nascimento’s book MONKEYS: Monologue in 9 episodes and 1 act, published by Cobogó.

Nascimento ends the performance with a flag bearing the faces of dozens of Black people, residents of favelas and urban peripheries, victims of a racist State violence. Children, parents, and siblings who never got justice. At this moment applause fills the theater. But the applause is not just for the actor and his work. It is, above all, for the victims of Black genocide and their families who have no alternative but to live with grief while they struggle.

The play does not end with the applause, however. At the Rio de Janeiro performances, Nascimento invited Eduardo’s mother, Theresinha Maria de Jesus, to the stage to share her experience of loss, grief, and struggle. Nascimento and de Jesus believe that art can also be a form of justice. Giving visibility to the murdered child is a way of bringing little Eduardo back to life, even if just for a few minutes, in a few scenes. The audience usually responds to de Jesus’ account with a resounding #JusticeforEduardo. She has stated in interviews that public pressure generated by the play may result in her son’s case being reopened after years of being closed by the courts. For de Jesus, Macacos has been, most of all, a source of hope.

View this post on Instagram

About the author: Cleyton Santanna holds degrees in journalism and screenwriting from Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ) and the CriaAtivo Film School. He uses his YouTube channel to address oddities, ancestry, and Afro-Brazilian culture. In 2017, he produced two documentaries: “Entre Negros” (Between Blacks) and “Tudo Vai Ficar Bem” (Everything is Gonna Be OK), and was recognized as a screenwriter in 2018 by the Creative Economy Network for the short “Vandinho.” He is currently a communicator for the Museum of Tomorrow and hosts the Influência Negra podcast.