Clique aqui para Português

On this World Water Day, March 22, 2024, this video-report with English subtitles brings testimonials from residents of various communities, showing that access to and the quality of water have been deteriorating among Rio’s favelas since the privatization of CEDAE and under the responsibility of private utility Águas do Rio. These are some of the many complaints that RioOnWatch has received and accompanied in various favelas across Rio de Janeiro over the past two years.

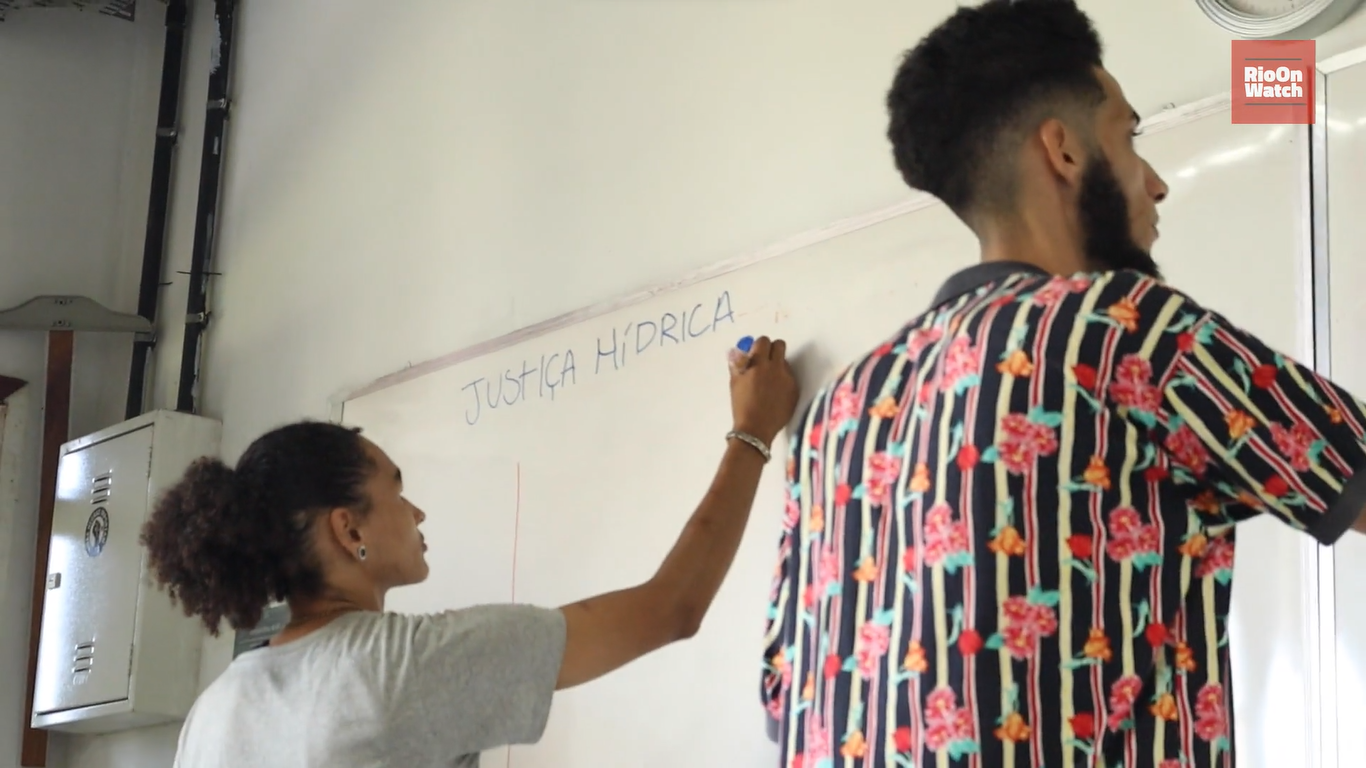

This video-report brings images from the latest local data launch from the report “Water and Energy Justice in the Favelas: Community Researchers Gather Data Revealing Inequalities and Calling for Action,” covering 15 favelas across Rio de Janeiro, held at Galeria Providência, and from the seminar “Access to Water in the State of Rio de Janeiro: Struggles and Experiences Against Commercialization.” On both occasions, residents denounced the worsening water supply following the privatization of CEDAE.

“When the process of potentially privatizing CEDAE started and Águas do Rio took over, I believe they did a fast food job to be able to claim that several communities were benefiting. They didn’t consult the residents, they made an agreement amongst themselves and started a top-down implementation.”

“For us to have access to water, people wake up at dawn to fill up every vessel. Then we get our children ready to go to school. There’s also no water at the school, on top of not having classes for our children. So, you have to find someone to take care of the children, so you can search for or go to work and do your daily errands. After the new company entered the market, we no longer have water, at least not on my street and at my daughters’ school… I work in the South Zone, I am a cleaner in the South Zone. It’s funny, all the time I wash and iron without problems in the South Zone. I want to know: why are the people from the South Zone better than me, living on Livramento? And the people who live in the Pavão-Pavãozinho/Cantagalo favela complex? Águas do Rio doesn’t knock on their doors to find out how many people live there, to charge them. And then, I, Letícia, don’t have any water. Why? Am I worse than them? Don’t I have a right to water? The problem is not [paying] the water meter. I have five girls, I’m a single mother. If they put a water meter at my house, and I had water all day long, I wouldn’t mind paying a fair price… It just feels like we’re asking for a favor, while I see the situation in the South Zone, where everyone has water. And me, waking up at dawn to get water. It’s neglect, you know?”

“There was a time when the water was very bad. It was giving us stomach aches. The water was a brownish, murky, clay-like color and with an unbearable smell. So much that to this day, at home, we buy mineral water to drink. Because you can’t drink water like that.”

Residents highlight that many of the advancements in the favelas regarding water were built by their own hands.

“We are not even permitted access to water. And if there is water, it’s because there is community organizing: ‘We break the ground, we lay pipes and we make the water arrive.’ And it’s thanks to these efforts that we have water, we have electricity, we have roads.”

Watch the Video-Report Here (with English subtitles).