Clique aqui para Português

On March 14, 2018, six years ago, a barbaric crime took the lives of Rio de Janeiro Councilwoman Marielle Franco and her driver Anderson Gomes. A date that will never be erased from Brazil’s and the world’s memory, a world that united in mourning and indignation, demanding justice. However, to this day, her political femicide remains unsolved. It is still unknown who ordered Marielle Franco’s killing, and why. Since then, there have been many allegations that authorities have been hindering investigations into this heinous crime. We now mark six years of continuous re-victimization of the families of these two favela natives: Marielle, from Complexo da Maré, and Anderson, from Complexo do Alemão.

Six Years and Still an Unresolved Political Crime

The lack of a solution to this political crime exposes how fragile and inconsistent public security is in the state of Rio de Janeiro. Not only for failing to protect an elected official in the exercise of her duty, but also for tolerating maneuvers to cover up for those responsible. Today, even though there are two men in prison for her execution, Ronnie Lessa and Élcio Queiroz, the authorities have not identified the mastermind behind the crime. The motivation also remains a mystery.

“The brutal execution of Marielle and Anderson is an affront to democracy. It is an affront to the lives of all Black women. It is an affront to the LGBTQIAP+ community. It is an affront to the favela. It is an affront to the poor. Marielle was executed in such a brutal manner that it terrorized the world.” — Camila Marins, journalist

The ease and sense of tranquility that the killers had in planning the attack, following the vehicle, setting up an ambush, and shooting an elected representative, near Rio de Janeiro’s downtown, only a few kilometers from City Hall, is testament to the vulnerability to which Black bodies are subjected.

Giniton Lages, the first investigator to delve into the crime and author of the book Who Killed Marielle?, stated early into the investigation, in an interview with Intercept Brasil, that “someone gave privileged information to the criminals.” At the time of the murder, Lages was not yet in charge of the Civil Police’s Homicide Division but became its supervising agent and took over the councilwoman’s case three days after her assassination. Under his leadership, almost a year later, Marielle’s killers were arrested. Lages was chosen due to his success in leading the investigation into Judge Patrícia Acioli’s assassination in 2011. However, a few days after the arrests, he was removed from the case in March 2019.

Both Élcio Queiroz and Ronnie Lessa remained silent for years, until Queiroz testified in 2023. His partner, Lessa, followed suit in 2024 and agreed to a plea bargain, where he implicated Domingos Brazão, an advisor for the Rio de Janeiro Auditory Court (TCE-RJ), as “possibly” ordering the crime. Brazão denies the allegations, leaving the case unresolved and under judicial secrecy.

Domingos Brazão, however, was not the first politician implicated as a “possible” orchestrator, highlighting the long-standing issues of inconsistency, irresponsibility, and political interference plaguing the investigative process.

Frequent changes in investigative leadership and direction, along with high staff turnover, underscore the lack of consistency and integrity in the Marielle Franco case. This pattern was evident not only within the Rio de Janeiro Civil Police (PCERJ) but also within the Rio de Janeiro State Prosecutor’s Office. In 2021, just a few months after Giniton Lages was removed from the case, prosecutors Letícia Petriz and Simone Sibilio sought to be relieved of their duties due to changes that hindered the progress toward solving the crime. With the departure of these three key figures from the investigative team, years have passed with minimal progress.

“This delay… is, indeed, so that we don’t find out who’s behind it… [but we press on] with heads held high and with all the competence to govern. Therefore, knowing who ordered Marielle to be killed also means understanding—not just for us who already know—but for the entire country, a city, a state… what institutional and structural racism does to our lives.” — Monica Cunha, founder of Movimento Moleque and city councilor for Rio de Janeiro

The ongoing perception of inefficiency and political interference in the state-level investigations led to much discussion, and even campaigns about whether or not the case should be federalized. However, in 2023, former Minister of Justice Flávio Dino decided that the case would not be federalized, but that the Federal Police (PF) would act in parallel and in support of the Civil Police and Public Prosecutor’s Office of the state of Rio de Janeiro. To this end, the former minister ordered the opening of an investigation by the PF into the councilwoman’s femicide. According to PF sources, the case is finally progressing, and a well-supported answer regarding who ordered the murder of Marielle Franco is expected by the end of 2024.

About Marielle Franco

But, after all, who was Marielle Franco? Today, her name echoes across the world. Marielle Francisco da Silva was a daughter, a sister, a mother, a wife, a parliamentarian and a favela-born activist committed to myriad causes. This was the figure that they tried to silence. She was the daughter of Marinete da Silva and Antônio Francisco da Silva Neto. She was the sister of Anielle Franco, now Minister of Racial Equality. She was the mother of young Luyara Franco. Black, female, queer, a daughter of poor migrants living in a favela, education was a way to reach unimaginable places.

Countering prevailing statistics, Marielle Franco forged her educational path through a community-based foundation. She began her journey at community-based organization Center for Studies and Solidarity Actions of Maré (CEASM), where she got support preparing for university entrance exams. From there, she enrolled in undergraduate studies at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio), majoring in Social Sciences with the support of a federal Prouni scholarship. Later, she earned her master’s degree in Public Administration from the Fluminense Federal University (UFF). For several years, she served as parliamentary advisor to Marcelo Freixo and as coordinator of the Human Rights Commission at the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly (ALERJ). In 2016, she was elected city councilor, ranking as fifth most popular candidate in that election.

“Marielle’s strength and courage continue to defiantly echo. Her legacy embodies the political style and unique identity of a Black woman activist and feminist who refused to be silenced.” — Edmeire Exaltação, sociologist and director of Casa das Pretas

According to Camila Marins, journalist and master’s student in Public Policy, specializing in Human Rights at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), this historic vote was no accident. Marielle succeeded because many people felt represented and saw themselves in her.

“Marielle represented many of us, Black women who dare to dream of a world with more justice and solidarity. She represents Black women who dare to challenge and destabilize structures, to engage in politics. When we enter these spaces of power, we do so in our own way: with our ethics, our aesthetics, our feminist quilombo ethics.” — Camila Marins

For social worker Ana Gilda Soares dos Santos, Marielle’s assassination was a message to Black women and a reinforcement of intimidation for Black and favela communities as a whole. However, for her, after this political crime, the battle cry is: “for each one of us who falls, ten will rise.”

Marielle was always on the move, always committed to her mission. And that is exactly what Edmeire Exaltação, who directs Casa das Pretas, the last place Marielle was in life, recalls when speaking of the parliamentarian and activist from Maré.

“She was a Black woman activist, a tireless leader, and an embodiment of the feminist movement, especially the Black women’s movement in Rio de Janeiro. Sadly, she was the victim of cowardly, misogynistic violence, reflecting the most inhumane aspects of Brazilian politics. As a young, Black councilwoman, she represented hope and determination for the voices of Black women to be heard, and she had a promising future that was tragically cut short. Her death was a devastating setback in the fight for social justice and equality for women, leaving an immense void.” — Edmeire Exaltação

About Anderson Gomes

And what about Anderson Gomes? Anderson Pedro Gomes was married to Agatha Arnaus and was the father of Arthur, who, at the time of the crime, was only one year old. Born and raised in a favela, like Marielle, he hailed from Morro da Fazendinha, in Complexo do Alemão. On the night of his murder, he was working as a substitute driver for the parliamentarian. While driving her home after an exhausting day of work on March 14, 2018, he was shot in the back alongside the councilwoman.

Just before the crime, Anderson called his wife and mentioned that he was looking forward to watching his soccer team, Flamengo, play in the Copa das Libertadores. Anderson was a worker, a 39-year-old favela native full of dreams, whose life was interrupted by the ambush of a political crime with which he had no real connection.

Black Women’s Insurgency

“Marielle Franco was born to be a compass, to determine that there could no longer be just one Black woman in parliament at a time: we go in as a group, period! The representation and legacy that Marielle left us tells us that we have to be everywhere that we want to be. That we, who were born Black, need to truly occupy our space within this city, within this State, within this country that is ours, that we built.” — Monica Cunha

Affirming their commitment to the legacy of Marielle Franco, many Black women emerged from mourning into action: Renata Souza, Monica Francisco, Camila Marins, Silvia de Mendonça, Thais Ferreira, Talíria Petrone, Tainá de Paula, Monica Cunha, Benny Briolly, Dani Monteiro, and many others who, even in the face of barbarity, refused to back down. They continue to make history and engage in the constant struggle to guarantee human rights for Black Brazilians.

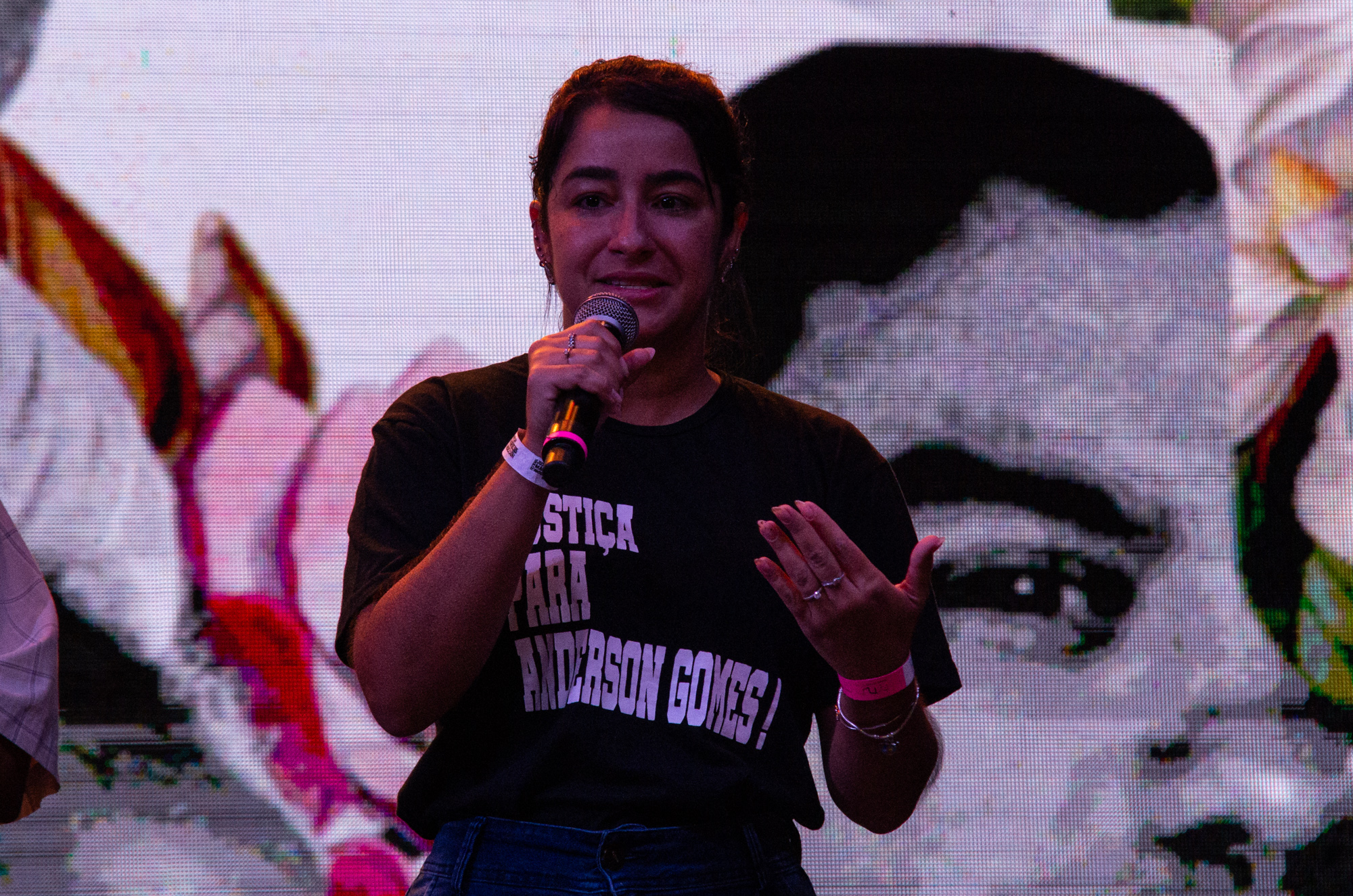

Similarly, the calls for justice will not relent. It is crucial to remember that the lack of answers regarding the case of Marielle Franco and Anderson Gomes is a disgrace of the Brazilian State, remaining unresolved six years later. Their unpunished murders cast doubt on Brazil’s very democracy. That is why, on Thursday, March 14, another edition of the Justice for Marielle and Anderson Festival took place at Praça Mauá, starting at 5pm in Rio. Free of charge, the event brought together various artists, some of whom hail from Complexo da Maré, Marielle’s birthplace.

About the author: Cynthia Rachel Pereira Lima, a native of Rio and a resident of the city’s North Zone, holds a master’s degree in Culture and Territorialities from the Fluminense Federal University (UFF). Currently, she is part of the Feminine Crossroads Collective, where she wrote and directs the play “Feminine Crossroads” (2018); “The Boy Omulu” (2019), “Until the End – Women, Memories, and the Like” (2020). She is also involved in the Black on Stage project, which documents the Black scene.