Clique aqui para Português

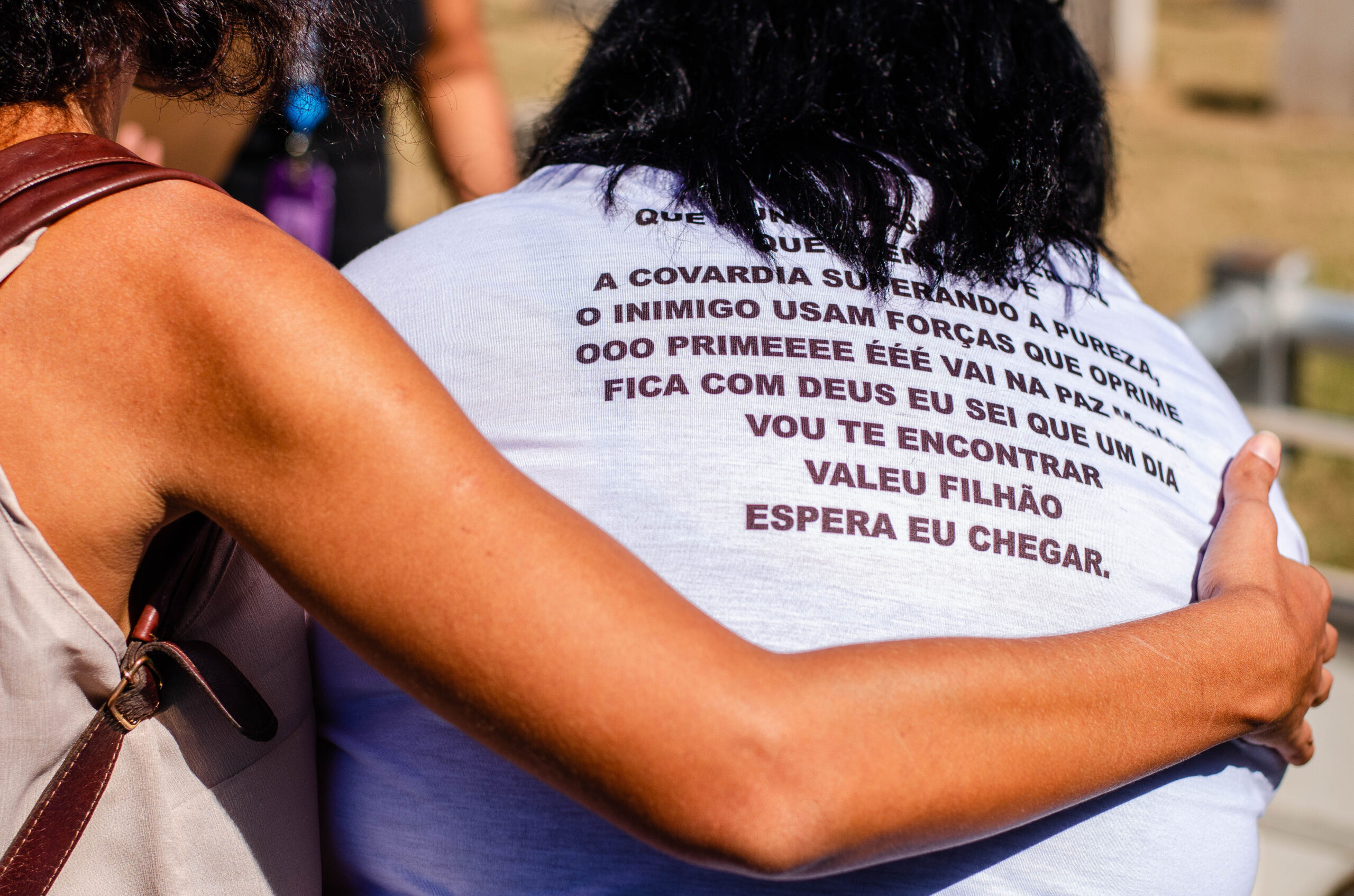

Three years have passed since the Jacarezinho Massacre, during which Rio de Janeiro’s Civil Police (PCERJ) killed 28 residents in the deadliest police operation in Rio state history, the pain still plagues the Jacarezinho favela, particularly on Mother’s Day. One day after the day that celebrates motherhood, Maria Conceição* and Solange Silva* were once again fighting to force authorities to reopen investigations and guarantee dignified funeral rights for their late children. They decided to exhume their sons’ bodies of their own accord. On their laps, they bore not gifts or flowers, but boxes with their sons’ remains. But these mothers do not want flowers: the Mother’s Day gift they ask for is justice for their children.

Victims’ Families’ Lives Must Go On

The Jacarezinho Massacre was a traumatic event that left a profound mark on the history of Rio de Janeiro and generated social outrage. And yet the families of the victims are still struggling to cope with their grief and with the impunity surrounding the case. Though painful, the exhumation of their children’s bodies is viewed as an opportunity to reopen investigations into the massacre and ensure that those responsible are punished.

For the families, the exhumation represents a crucial step in their search for justice and truth. By analyzing the bodies, the families hope to obtain more information about the circumstances of the deaths, thereby strengthening calls to hold agents of the State accountable. However, the exhumation prices charged by cemeteries are cost-prohibitive, once again rendering these families victims of the State.

“When [the end of] May comes around, [our children] will have to come out of that grave because the three-year deadline is coming up. And we have three options: cremation, which is R$4,000 (US$777); a columbarium, which is over R$7,000 (US$1,360); or a drawer, which is almost R$15,000 (US$2,915). These amounts are clearly out of reach for many mothers and families, because most are single mothers.” — Maria Conceição*

The statement above was given by Maria Conceição*, 52, one of the mothers still grieving the loss of her son during the 2021 Jacarezinho Massacre. In addition to Conceição, 27 other families are still racing against time to raise the necessary funds to guarantee the bare minimum: a worthy place for their children’s memory to rest and to remove their sons’ bodies from a nameless tomb.

“Just like me, many favela families and mothers do not have the means to pay to remove the identification number on the grave and cover it with our children’s names, a photo, their birth and death dates. My son has become just another number like the other boys.” — Maria Conceição*

She recounts that her whole family mobilized to raise the money. She also started a raffle to secure funds for the exhumation. Despite all her efforts, Conceição has been unable to raise all that’s needed. However, she continues to believe in the support that the Rio de Janeiro State Prosecutor’s Office and the Public Defenders’ Office have offered to the families, and in the possibility of obtaining free exhumation services. Like Maria Conceição, dozens of other families are unable to afford the exhumation and a final resting place for their children’s remains, and continue paying the price for the injustice that led to their deaths in the first place.

Despite the suffering of these families at the hands of the State, according to Guilherme Pimentel, former general ombudsman of the Rio de Janeiro Public Defenders’ Office and technical coordinator of the Network for Assistance to People Affected by State Violence (RAAVE), in Brazil, public policies guaranteeing the right to mourn for people living in poverty are very precarious. There are no legal provisions or defined parameters to grant free funeral services, including exhumation.

“The fact remains that Brazilian legislation is flawed and does not provide for the right to free exhumation. This is a problem that must be resolved, as the right to mourn is very precarious. All rights related to mourning, from cemetery services, removal of the deceased, clothes, coffin, wake, burial, grave, tombstone, etc. All of these services, including exhumation, are a set of rights, termed ‘the right to mourn,’ but they are very precarious in Brazil. In the case of exhumation, individuals do not have access to free services. There is no law, norm, or rule that defines this right. Free burials exist, but they are extremely precarious. Based on municipal decrees, they do not offer the right to a wake and the coffins are very low-quality… That sums up the precariousness of the right to mourn! In some cases, there is still some semblance of a free service, concerning the burial, for example, but it is still very low-quality, difficult to access… just awful quality… [The lack of] the right to mourn and this precariousness [cause] a pain that never truly goes away… Grief has a function in people’s lives, which is to turn the page… that’s when this pain will be able to go away… and that page never turns when you lack a guaranteed right to mourn.” — Guilherme Pimentel

Solange Silva*, 49, a single mother, told RioOnWatch about the loss of her son to State-sanctioned violence and shared a bit about the preparation to exhume her son’s body on May 13.

“I have to pay approximately R$9,000 (US$1,750) for my son’s exhumation… Apart from the box I need to place his remains, which costs a little over R$1,000 (US$195)… I sold clothes and sneakers on the street. I sold them in Uruguaiana, in Madureira, in São Cristóvão at all hours of the day and night. I did it so that I could have some money [saved] from January until now. I worked so much, I couldn’t remember anything. I only stopped to rest when I’d stop to have a sandwich and a soft drink at the end of the afternoon. By the end of April, beginning of May, I couldn’t take it anymore. I now rely on medication to sleep.” — Solange Silva*

Fabbi Silva, current ombudswoman of the Rio de Janeiro Public Defenders’ Office, explains how the Nucleus for the Defense of Human Rights (NUDEDH) and RAAVE have been working with the group of mothers from Jacarezinho to provide mental healthcare. “The main point of RAAVE and NUDEDH is to support families and enforce rights and public services, so that family members can escape the cycle of pain and mourn with dignity,” reiterates Silva.

For nearly a year, these mothers have been asking for support and looking for alternatives to obtain exhumation and a dignified funeral for their children. In addition to fighting for free services, there is hope in producing new evidence based on novel analyses of their children’s exhumed remains and interest in reopening the cases.

“In the case of burial, there are regulations that guarantee the service is free… However, there are several issues regarding the quality of the service… What is happening with the family members of the Jacarezinho Massacre victims is that, right now, they—the more than 20 mothers—are fighting for the exhumation process which, unlike burial, is not free. It is a very expensive service… For a year, they have been fighting and asking for support to find alternatives, bearing in mind that many of them hope to reopen the cases concerning their children. If the final arrangements are carried out in the usual way, with the incineration of the remains, these mothers fear losing evidence that may be requested by a judge if the cases are reopened.

Therefore, the push for exhumation is to ensure proper care with respect to evidence that may, perhaps, exist. And also to ensure that a proper resting place for the remains is provided, considering that this mother, this family member, does not want to say goodbye in this way, not knowing where their loved one is buried, whether in a box or in an urn… What the Public Defenders’ Office has been working on, through RAAVE, the Public Finance and Collective Protection Center and NUDEDH, is listening to this process… and considering less painful avenues during the exhumation phase, guaranteeing the families’ rights to custody over the remains for an indefinite period of time.” — Fabbi Silva

However, despite this fight for exhumation, many mothers decided to cremate the remains, because that way, at least they will know what happened to their children’s bodies and will have their ashes to perform their chosen end-of-life rituals. After three years and one month of their loved ones being buried in temporary graves or rented gravesites, if a family has no financial means or expresses no interest in the removal and destination of the remains, the cemetery itself will handle the process. In this case, the bones are sent to the cemetery’s general ossuary, where they will be mixed with those of other people for subsequent collective incineration. At that point, one’s remains can no longer be identified and these mothers would, once again, be left without the right to properly mourn.

Many mothers have decided to go the cremation route because they do not have the resources necessary—thousands of reais—to cover exhumation costs, nor do they want to see what is left of their children disappear forever. Therefore, one of NUDEDH’s current priorities has been filing lawsuits to obtain authorizations for cremating the remains of the victims of the Jacarezinho Massacre. However, according to the ombudsman, the deadline to resolve this issue is very tight: they only have until May 30 to file cremation requests. As of May 23, 16 mothers have already signed the documents.

‘Is This His Final Resting Place? Mother’s Day Is Done For Me.’

During the exhumation of her son’s remains on May 13, Silva* was accompanied by her partner and three employees from the Public Defenders’ Office: two psychologists and the ombudswoman.

“This week was very difficult for me. My son was killed on Thursday, May 6, and my birthday is on May 1… Three of my peers, who were part of our group, couldn’t handle it and slipped into deep depression. And now they are dead… I’ve also been experiencing horrible depression!” — Solange Silva*

At the time of the massacre, Silva* remembers how her son came up with the idea of celebrating her birthday on Mother’s Day, which fell on May 9 in 2021. However, by the time May 9 came around and they were meant to celebrate her birthday, she was lying atop his coffin.

“If only we could speak up about everything we witnessed, to mobilize an investigation that exposes all that the police did… but, unfortunately, many people also feel afraid and it is a horrible feeling. It’s like we no longer have a life because we live in a situation of perpetual neglect. If we can’t work with names, work with all the information we have on the police, we won’t get justice.” — Solange Silva*

Even with the psychological support provided by the Public Defenders’ Office, she says her days have been quite difficult. In addition to her son’s death, she remembers the disinformation spread by the State and fake news that still circulates on social media about her son, his murder and even about her, the mother of a victim of the State. Silva* laments she now needs to take over ten medications to control the health problems resulting from the three years she has lived following the massacre. Conceição* also experiences health issues as a consequence of the massacre: high blood pressure, diabetes, anxiety attacks, and depression.

“When we experience this type of situation of police violence, they forget that these young people have a family. The justice system just wants to know if they have any criminal record.” — Maria Conceição*

Police Operations That Kill and Bring Zero Justice

According to a study on police massacres, between 2016 and 2023, the Fogo Cruzado Institute documented 283 police operations in Rio de Janeiro that would be characterized as massacres, resulting in 1,137 civilian deaths. On average, there were three massacres per month.

The Institute reported that among the massacres mapped, 18 occurred after a police officer was killed or injured. These massacres, referred to by residents as Revenge Operations, are, on average, 71% more lethal than police massacres in which no public officer was shot or killed. Revenge Operations have resulted in 117 deaths in Greater Rio since 2016.

This was also the case with the Jacarezinho Massacre. The Civil Police conducted an operation that lasted about ten hours. At first, it was relatively calm. The massacre began after a police officer was shot and killed in a confrontation shortly after the operation started. In addition to the intense conflict that followed the death of the Civil Police officer, months later, police officers were accused of torture, as well as forging, defrauding, and lying to cover up executions. During the police action, due to the gunfire, train services on the Saracuruna and Belford Roxo lines, as well as on Rio de Janeiro Metro Line 2 were interrupted. A Family Health Clinic and Covid-19 vaccination centers were closed. Over 2,000 students missed class, and people were shot even outside the favela, including inside a subway car passing through Triagem Station, which serves the North Zone neighborhood of Rocha.

While police massacres take place across Greater Rio, their occurrence is not uniform throughout the region. In the city’s South Zone, nine massacres were recorded, with four of them occurring in the Rocinha favela. In the North Zone, there were 73 massacres that killed 373 people. In Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region, 72 massacres were mapped, resulting in 255 deaths. In the Leste Fluminense (Greater Rio’s Eastern Region), there were 70 massacres with 252 deaths.

Complexo do Salgueiro, a cluster of favelas in São Gonçalo—a city in Greater Rio’s Eastern Region, to the east of Guanabara Bay—recorded the most massacres during the study period. In Complexo do Salgueiro alone, 14 police massacres resulted in 66 deaths. To understand the magnitude of what happens there, here are the other four locations with the most police massacres: Complexo da Maré with 10 massacres and 51 deaths; Complexo da Penha with 8 massacres and 55 deaths; City of God with 8 massacres and 27 deaths; and Vila Kennedy with 8 massacres and 26 deaths.

The Fluminense Federal University’s Study Group on the New Illegalities (GENI/UFF) published a report with data from 2007 to 2022. During this period, 19,198 police operations were carried out in Rio de Janeiro. Of these, 629 resulted in massacres, totaling 2,554 deaths. In Greater Rio, massacres occurred in 3.3% of police operations but were responsible for 40% of deaths during police operations. Historically, the victims of State-sanctioned massacres are overwhelmingly Black and live in favelas—especially those in peripheral areas. This was also the case in the Jacarezinho Massacre: 28 young Black men were murdered in this North Zone favela.

RioOnWatch contacted the Rio de Janeiro state press office asking about possible support for the families presently exhuming the bodies of their family members who were victims of the State. At the time this article was written, we had not received a response.

*The interviewees’ names are fictional to protect their identities and privacy.

About the author: Ramon Vellasco is a freelance photojournalist and reporter, born and raised in Vila da Penha. He focuses on issues related to human rights, culture, education, diversity, and marginalized social groups, primarily working in peripheral, favela, areas.