Clique aqui para Português

This article is part of RioOnWatch‘s series on Memories of Favela Power, which documents and celebrates the history of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas through narratives and reports from residents’ collective memory, in their daily struggle to lead fulfilling lives.

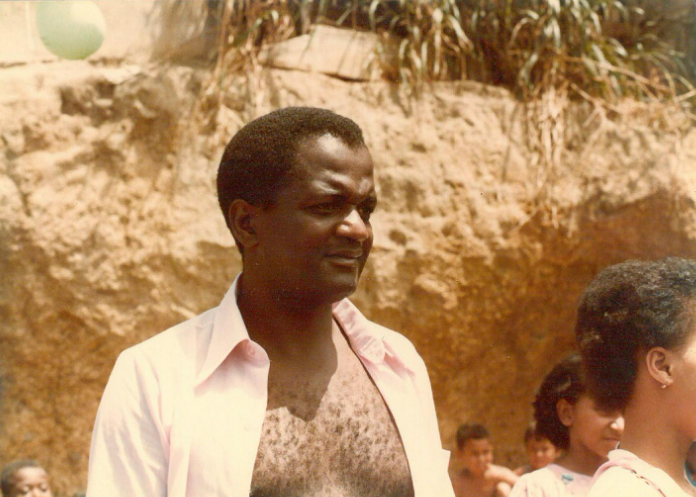

It is impossible to tell the story of Vidigal, the favela in Rio de Janeiro’s South Zone seen by every visiting tourist at the end of Leblon beach, without mentioning Carlos Raimundo Duque, an important local leader. Born on April 26, 1945, Duque moved with his family to Vidigal at the age of five.

“This was all bush. There were about 25 houses covering the entire area of the favela. Usually, someone had a little house here and fenced off the whole area as if it were a small farm. People used to raise cattle, pigs, goats… all of them roaming freely!” — Carlos Duque

Seu Duque and the Fight for Tenure Security in Vidigal

Seu Duque, as he is known by younger generations, participated in the founding of the Vidigal Residents’ Association (AMVV) in 1967. Even before the institution was established, he was always present at community meetings that took place in the 314 area, at the terreiro [a sacred space of Afro-Brazilian worship] of the babalorixá [Candomblé priest] known as Father Modesto.

The AMVV was founded to curb the removal attempts that Vidigal had been facing since the 1950s. However, the attempt to evict residents was most intense in 1977. There was interest in building luxury housing in the area of the hill called 314, where Seu Duque lived.

He and other leaders, such as Armando Almeida Lima, Carlos Pernambuco, and Mário Sérgio, who were part of the AMVV, led the residents’ resistance. At the time, it was proven that the imminent risk of landslides in the area was a ruse to replace favela residents with a wealthier public who intended to build mansions in the spot.

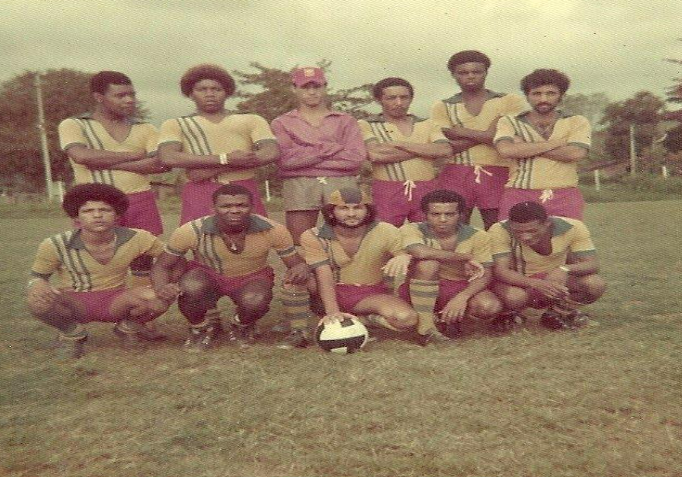

Carlos Duque was the mastermind behind various strategies used to build a sense of collective belonging. For example, in order to gain residents’ support for the community struggle being organized by the AMVV, Seu Duque appealed to Brazil’s national passion: soccer.

When the second leadership team for the AMVV was formed, Seu Duque held the position of vice-president and created a local soccer team, Niemeyer Futebol Clube, as a strategy for developing and strengthening Vidigal’s identity. Due to the red color of their shorts and the fact that most of the players were Black, the team became known as “Saci,” referring to the magical one-legged Black boy from Brazilian folklore who smokes a pipe and wears a red cap; thus the origin of the team’s nickname. Though it is said that the players did not have much skill with the ball, Seu Duque’s intention to create a sense of community was achieved.

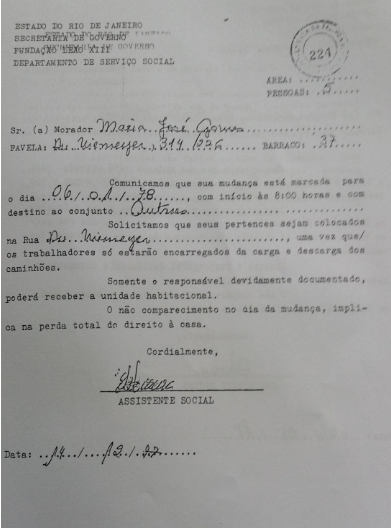

In October 1977, eight years before the end of Brazil’s Military Dictatorship, removal notices issued by the Leão XIII Foundation arrived in Vidigal. Trucks from the waste management utility, COMLURB, transported residents and their belongings from area 314 to Antares, some two hours away in the city’s extreme West Zone. The housing complex offered there by the Rio de Janeiro city government lacked public amenities and infrastructure, not to mention it was distant from job opportunities and the social bonds previously developed in the South Zone favela.

Seu Duque then came up with another resistance strategy. He contacted Eneida Brasil, principal of the Almirante Tamandaré Municipal School located in Vidigal, and requested support.

“We spoke to Principal Eneida Veloso Brasil [after whom a street was named in Largo do Santinho]. She agreed, and we put the children from Almirante Tamandaré right up front. When the COMLURB truck arrived, there were no belongings out on the street. This was in October, so we informed the mayor at the time, Marcos Tamoyo, that if we were to relocate to Antares, the children would risk being held back a grade at school.” — Carlos Duque

The attempts at forced eviction persisted. Duque was the driver for the Catholic school Stella Maris, located at the foot of Vidigal. Being a Catholic himself, and well-regarded as a professional at transporting the well-off students from the school, he gained support from the school’s nuns for the favela’s cause. Thus, at Carlos Duque’s request, the nuns declared a day off from classes and lent him school buses, allowing him to take the residents threatened with eviction to visit Antares. The strategy proved successful.

“They started convincing our women by saying that they would have a two-storey house in Antares, so they wouldn’t get attached to the view [from Vidigal]. I asked to borrow a bus from the mother superior at Stella Maris School and took people to see the houses. There were no classes at school that day. We got seven buses and took a whole bunch of women and children to Antares. It looked like a concentration camp. A sea of nothing. Not a single tree. The buildings looked like pigeon houses. A rusty water tank… We let the women loose there and I said: ‘You have one hour.’ There were already people there, coming from Praia do Pinto [a favela removed at the time which had been in the wealthy South Zone neighborhood of Leblon] and other [displaced] favelas. Coming back, the women were furious. We took about three hundred people. After that, we didn’t even need to campaign. They didn’t want to move there at all!” — Carlos Duque

This closeness between the leaders of Vidigal and the Church caught the attention of other Catholic sectors. Renowned law scholar Sobral Pinto, a Catholic and a personal friend of Archbishop Dom Eugênio Sales, appointed attorney Bento Rubião, a member of his law firm, to represent the favela’s cause. In 1980 the residents won the right to stay. According to residents, this was the first case in history where the eviction of favela residents was overturned through judicial means.

The context of struggle of Vidigal’s residents against forced eviction led to the founding of the Catholic Church’s Favelas Pastoral Committee in 1978. The successful experience of partnering with sectors of the Catholic Church was extended to other favelas, which also received legal support from renowned lawyers to ensure their right to remain in their home territories. The Pastoral Committee Notebooks (1979) report that, including Vidigal, the lawsuits benefited about 10,000 families living in various favelas: Conjunto Cardeal Câmara, Senador Camará, Cantagalo, Morro São Bento, Loteamento Santa Rosa, Morro dos Cabritos, Chácara do Céu, Vigário Geral, and Morro da Formiga.

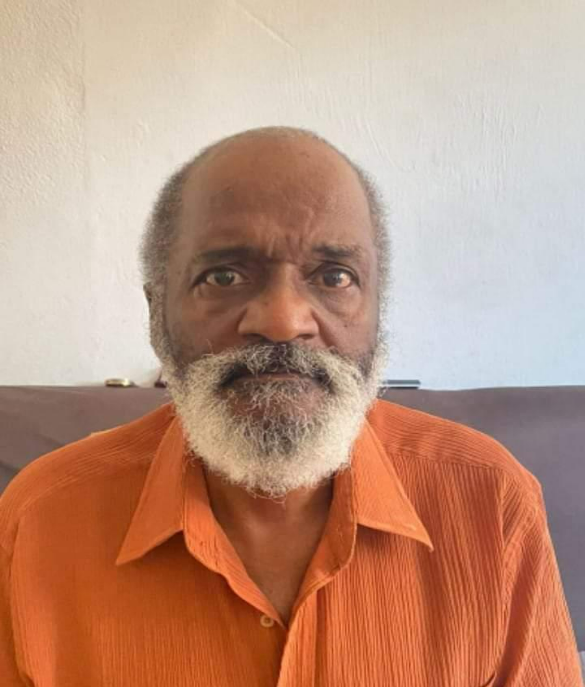

A Life Dedicated to the Right to Housing

Carlos Raimundo Duque is a key figure in Vidigal’s history and in the organization of Rio’s favelas more broadly. Besides being a leader against forced evictions, he served as president of the Vidigal Residents’ Association (AMVV) and director of the Federation of Favela Resident Associations of Rio de Janeiro (FAFERJ) from 1979 to 1988. Duque played a crucial role in restructuring the institution representing favelas when civil society organizations, which had previously been declared illegal by Brazil’s Military Dictatorship, were reinstated.

Although the dictatorial period lasted until 1985, militarization persists in the favelas to this day. To ensure that the Brazilian State recognizes and remedies the persecution suffered by favela leaders and members of FAFERJ during the Military Dictatorship, the institution recently submitted a document to current Minister of Human Rights and Citizenship Silvio Almeida requesting a Declaration of Collective Political Amnesty.

Seu Duque is part of this history, although he states that at that time he had no political inclination, that he was just “defending the right to housing.” At the end of the 1970s, FAFERJ was weakened due to persecution by the prevailing political regime. Duque, along with leaders like Irineu Guimarães from Jacarezinho (a favela known at the time for its political activism alongside the Brazilian Communist Party, PCB), broke away from the clientelistic politics then adopted by the institution and strengthened networked action, working with various sectors of society, including the Catholic Church.

However, his dedication to FAFERJ required time. He sought the collaboration of the youth of the time to continue the work carried out in Vidigal.

“When I went to FAFERJ, I saw that there was a youth group. I came here and told them to get organized, plan outings, and make proposals… I noticed that Paulinho [another historic local leader in Vidigal] stood out. So, I thought: great, now I can put together a board and dedicate myself solely to FAFERJ.” — Carlos Duque

Just like many others who fought against forced evictions, Seu Duque was honored with a street named after him in Vidigal. Ironically, Rua Carlos Duque, located in the upper part of the hill in the Bagulheiro area, today faces evictions and real estate speculation.

Access to several houses on the street has been prohibited since 2003. Despite this, with the implementation of the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) in Vidigal and the heightened interest from foreign investors, residents of Rua Carlos Duque have been receiving offers to sell their homes, which boast a breathtaking view of Avenida Niemeyer and São Conrado.

In February 2019, heavy rains hit Vidigal, resulting in one death and dozens of displaced individuals. In April of the same year, houses located on Rua Carlos Duque, which had never undergone containment works, collapsed, and residents of neighboring homes were relocated.

Rua Carlos Duque has sadly not repeated the history of the favela’s victory for the right to remain. It is thus all the more crucial that the history of our heroes be preserved and disseminated. These memories can recover paths of resistance from the past and adapt them to the present to envision a more dignified future for our favelas.

In parts of Africa, the griot holds knowledge and is tasked with transmitting it to future generations. According to the dictionary, “duque,” duke, is a title that designates leadership and nobility. We are proud to have this noble ancestral leader living in Vidigal. Here, in the favela, our duke is Black and a griot!

About the author: Bárbara Nascimento was born and raised in Vidigal. A Portuguese teacher in the Rio de Janeiro city and state public school systems, she holds an undergraduate degree in Modern Languages (from UFRJ in 2002) and a Master’s in Social Memory (from UNIRIO in 2019). She founded and directs the Vidigal Memories Nucleus, archiving and recording the collective memory of Vidigal.