This article summarizes some of the findings from the ongoing doctoral study ‘Collective Ownership and Housing Self-Management in Latin America: Contemporary Challenges and Horizons,’ by Pedro Lima, advised by Professor Raquel Rolnik, and funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) at the University of São Paulo (USP).

Is Collective Land Ownership a Reality in Latin America Today?

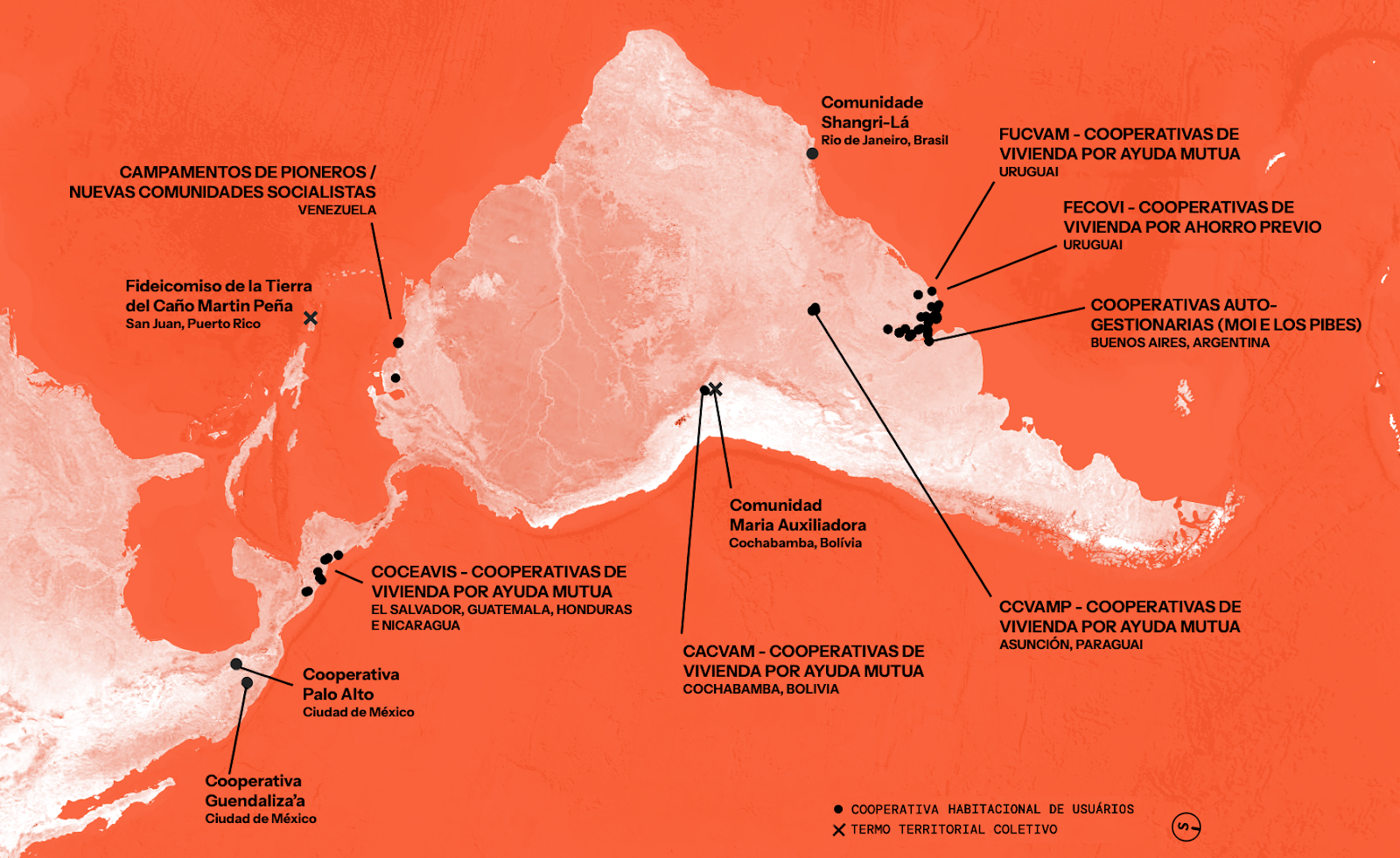

Currently, there are at least eleven countries in Latin America—plus Puerto Rico—that have communities or housing managed through collective ownership, either in the form of housing cooperatives or Community Land Trusts (CLTs). This article shares the results from a process to map and describe these areas, fruit of bibliographic research, review of materials produced by the communities themselves, or by researchers directly engaged in the projects, as well as visits and interviews with residents, leaders, and partners.

Uruguay offers the most expansive and noteworthy experience with housing cooperatives. The principles of the user system were largely developed there, influenced by Swedish practices as well as the traditions of peasant and indigenous communities in Latin America.

The cooperative is a collective organization of working families that together own the land and units, buildings, or houses. Each family is a member of the cooperative and occupies a housing unit. This means that all houses, buildings, and common spaces are collectively owned, and families can only use the units for living purposes—they cannot sell, rent, transfer, or speculate. If a family moves out, the cooperative share and the right to use the unit are not sold but transferred to another family without any increase in value, with the cooperative acting as mediator. Within families, the share can be inherited, and the right of use is for life.

The Uruguayan Federation of Mutual Aid Housing Cooperatives (FUCVAM) brings together over 500 mutual aid housing cooperatives (as well as those currently being established and under construction) in Uruguay, built through collective action. The Federation of Housing Cooperatives (FECOVI) represents cooperatives that use prior savings (ahorro previo in Spanish): they engage in self-management but hire companies or work cooperatives for construction. According to the survey conducted for this research, currently at least 85 of these housing cooperatives are inhabited.

Most of the cooperatives from both federations are located in the capital, Montevideo, as well as in cities throughout the country’s interior. Uruguayan cooperatives were able to develop thanks to public funding policies that were in place almost from the beginning of their history. Although there was a period of interruption in funding during the Uruguayan military dictatorship (1973-1985) and the early years of redemocratization, cooperatives regained a prominent position in Uruguayan housing policy in the 21st century.

Given the scale and significance of the Uruguayan experience, starting in the 1990s, FUCVAM began spreading its cooperative model throughout Latin America, focusing on mutual aid, self-management, and collective ownership. It participated in the creation of similar federations in other countries, combining its experience with the specific needs and knowledge of social movements and local organizations already working on housing issues.

The Paraguay Center of Mutual Aid Housing Cooperatives (CCVAMP) was formed in Paraguay, with at least four housing cooperatives and nearly 400 units in total. In Cochabamba, Bolivia, the Coordinating Committee of Mutual Aid Housing Cooperatives (CACVAM) was established, currently consisting of two housing complexes with a total of 42 units.

In Central America, the Central American Self-managing Coordination for Solidarity Housing (COCEAVIS) was created with four housing cooperatives in El Salvador (over 90 units), three in Nicaragua (about 70 units), two in Guatemala (about 20 units), and four in Honduras (over 400 units).

Although not an active participant, the Uruguayan experience influenced and maintains an open channel of communication with the Palo Alto (nearly 200 units) and Guendaliza’a (48 units) cooperatives in Mexico City, as well as with the six collective property cooperatives of the Occupants and Renters Movement (MOI) and the Los Pibes movement. There is also coordination with a total of 112 units in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and with the Pioneers’ Camps, a housing movement that occupies vacant land, mainly in the metropolitan region of Caracas, Venezuela, where it has built at least ten self-managed and collectively-owned housing complexes with about 1,000 units in total, which they named New Socialist Communities.

In addition to user cooperatives, another important form of collective ownership on the continent is Community Land Trusts (CLTs). In these contexts, land ownership is collective, held by an organization comprised of residents, while the ownership or leasing of units is individual. As with cooperatives, collective management of the land prevents speculation, keeping it accessible to low-income families and ensuring that the process of transferring units is mediated by the community. This approach aims to halt real estate speculation and gentrification.

According to the survey conducted throughout this research and beyond, there are at least two contexts with established and inhabited CLTs in Latin America: in Puerto Rico, where there are currently three CLTs, including the globally recognized Caño Martín Peña CLT, with over 2,000 participating families, and the Maria Auxiliadora Community in Cochabamba, Bolivia, with around 500 resident families.

There is also the prospective case of the Shangri-lá Community in Taquara, a locality in Jacarepaguá, a neighborhood in the West Zone of Rio de Janeiro. Originally established as a housing cooperative with 29 units, it is currently undergoing both legal and community organization processes to become a CLT.

Collective property ownership is recognized by local legislation in three Latin American countries: Uruguay, Paraguay, and Puerto Rico. In other countries, where this type of ownership is neither recognized nor regulated by the State, residents themselves characterize their form of ownership as collective and fight for its existence, maintenance, and recognition as such. These are, therefore, areas in struggle and dispute, seeking to sustain community organizing and their forms of collective property ownership amidst numerous threats, such as the lack of funding. CLTs enable collective land management in these contexts through a legal entity managed by residents.

Beyond the Individualization of Property

Transcending the hegemonic logic of property individualization following the construction of housing units, collective property serves as an important tool to prevent evictions and keep homes accessible for low-income and vulnerable groups. Moreover, in these areas, a variety of community-based socio-territorial practices are employed, extending beyond housing production to collectively address the numerous social and economic vulnerabilities faced by families.

These practices are made possible by collective property, or at the very least, are driven and strengthened by this form of ownership. They demonstrate that collective property, combined with self-management, can be much more than an abstract regulation; it becomes a living, dynamic exercise of the right to collective housing.

For many of the experiences that have collectively built housing complexes and the units where people live, collective property is synonymous with collective financing. This contrasts with the individualized housing financing we are accustomed to, where each family is responsible for paying their own installments and faces eviction in case of delay or non-payment. Collective financing means that the community secures a loan to build together, taking collective responsibility for paying all the installments. Thus, every month, families contribute their share of the financing but make payments to the bank collectively.

This mechanism provides families with greater security of tenure, as everyone is jointly an owner and beneficiary of the loan, so no single family can be evicted individually. Consequently, the responsibility for repaying the loan is not enforced by the threat of removal from an external agent, such as the government or a bank, but rather by the families’ commitment to the community.

In cases of default, collective property and self-management create space for alternative solutions to eviction that are more sensitive and supportive of the difficulties families face. For example, some large Uruguayan cooperatives with many residents have established an emergency fund system. This system collects a small monthly contribution from all residents to create a savings pool that can support families experiencing temporary financial hardships, such as unemployment or health issues. Additionally, as the number of smaller cooperatives in Uruguay grows and families face increasing economic challenges, the movement has successfully advocated for a state subsidy for loan payments. This subsidy helps prevent the poorest families from excessively compromising their income on housing and currently has a significant impact on the Uruguayan cooperative system.

In some territories, such as Palo Alto in Mexico and certain Uruguayan prior savings cooperatives, popular financing methods like credit cooperatives were tested in contexts where public financing was either cut or nonexistent. The Maria Auxiliadora community in Bolivia used pasanaku, an ancestral collective savings practice, to pay the technicians who contributed to project development.

If, on the one hand, these alternative financing methods emerge in contexts of limited State support and difficulties, on the other hand, they highlight the potential for financial autonomy within communities. While receiving funding can be beneficial, it can also act as a constraint, since, in many cases, the policies that provide communities with credit come with regulations and rules that can demobilize or hinder more creative community actions and political practices.

Over the years, the federations and movements behind these experiences, originally focused on housing as their primary goal, have also begun to develop practices in labor, consumption, and solidarity economy. Thus, the understanding of what can be built collectively to meet other needs continues to expand.

A community gardening project, focused on both consumption and sale, is being developed in Central American cooperatives. In some of these, productive cooperatives in various sectors have also been established, such as in Maria Auxiliadora (Bolivia) and in some of the Venezuelan New Socialist Communities. These initiatives aim to address the growing crisis in formal employment and the increasingly vulnerable conditions in informal work through the lens of the popular solidarity economy.

In 2020, the NGO We Effect (formerly the Swedish Cooperative Center), which supports most of the mapped territories, conducted a survey in various working-class areas around the world in partnership with UrbaMonde and the Cohabitat Network. The survey revealed that community-based and self-managed initiatives for producing, collectively purchasing, and sharing food and other essential resources were crucial for food security, sustenance, and health care during the Covid-19 pandemic. It also found that communities with collective property regimes, such as CLTs and cooperatives, were the ones that developed these types of actions most.

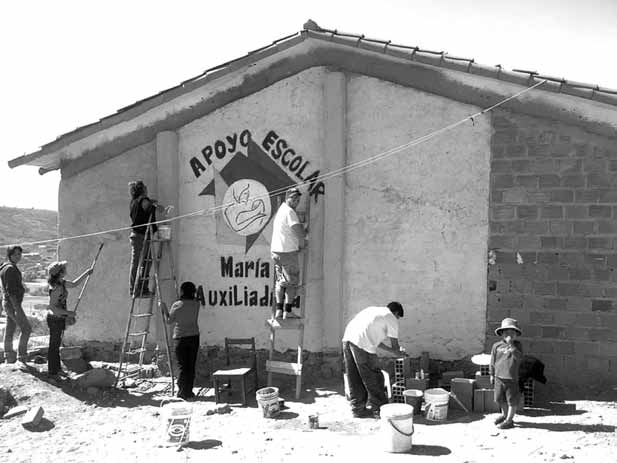

Various communities on collective property have built and manage social facilities open to the entire neighborhood. The vast majority of cooperatives in Uruguay, Mexico, Argentina, Paraguay, Venezuela, and Central America have salones comunales (community halls or centers), traditional spaces where assemblies are held, projects are developed, and parties and other community activities take place. These spaces are also made available to neighboring organizations or emerging cooperative groups. Many also include schools and daycare centers, such as the MOI cooperatives in Buenos Aires and the María Auxiliadora community in Cochabamba. They develop practices of shared care, bringing to the community sphere issues that were previously confined to the private sphere of families, often placing an additional burden on women.

María Auxiliadora also employs community-based methods to address violence, particularly gender-based, and domestic violence. This includes putting together committees for conflict mediation and using simple traditional tools, such as whistles, to alert the neighborhood to danger, in a context—shared by other areas—where the police are not a trusted institution. In El Salvador, there are instances where environmental and sanitation infrastructure has been built through mutual aid and is managed by the cooperatives themselves, benefiting not only their members but also their neighbors.

There are also low-cost health clinics, such as in Palo Alto, Mexico City. Guendaliza’a, in the same city, has a community restaurant. And Tebelpa, a historic FUCVAM cooperative in Montevideo, has a community market that sells products at cost to the entire neighborhood. These are among the remaining spaces from the 1970s and 1980s, when Uruguayan cooperative complexes developed several of these social facilities. They served as centers of resistance to the dictatorship and maintained the vitality of the working-class movement at a time when they were unable to build new housing complexes.

Today, with changes in the cooperative program, fewer resources, and the arrival of State and private sector facilities and services, new cooperatives face significant challenges in building these spaces. Most are only able to establish, at most, community halls.

This is a very important topic because, by building infrastructure and social facilities through self-management, communities do not merely create physical spaces or structures that mirror State-managed public facilities. Instead, they explore different management approaches, educational and health projects, and architectural designs, all grounded in local knowledge, popular needs, and the creative potential for alternative forms of collective care.

Additionally, there are movements that develop spaces for political and cooperative training: MOI’s guardías in Buenos Aires, which are spaces for welcoming and training new members; FUCVAM’s National Training School (ENFORMA), which chose a model of popular education inspired by Brazilian educator Paulo Freire and the active participation of cooperative members themselves in coordinating training activities; and COCEAVIS’ Regional School of Cooperative Training. These are essential spaces for ensuring that concepts such as collective property, self-management, and mutual aid are not only understood but embraced and renewed by new generations.

Many of these groups also participate in international networks, such as the International Habitat Coalition of Latin America (HIC-AL) and the Latin American Secretariat for Housing and Popular Habitat (SELVIHP), which promote the exchange of experiences, bring together forces in struggles, and disseminate these Latin American cases internationally. Throughout their journey, the movements aim to build awareness of the scope of their struggles: more collective and enduring than the individual fight for housing and much broader than the issue of housing itself, albeit stemming from it.

All the practices shared here represent ongoing attempts to address the diverse dimensions of vulnerability that families and communities face today. They embody a breath of hope from collective, working-class, and solidarity-based organization to resist, confront, and transform urban contexts increasingly dominated by individualism, authoritarianism, violence, and extractive logics. Thus, while powerful, they face numerous difficulties and contradictions in sustaining and developing themselves. It is therefore essential to celebrate and to learn from their experiences—as a way to inspire and inform new struggles. These experiences show that practicing alternative forms of property, away from the monoculture of private ownership, strengthens debates around alternative urban models.

Watch Pedro Lima’s Presentation (in Portuguese) on His Research:

About the Author: Pedro Lima is an urban designer, a Ph.D. candidate at the School of Architecture and Urbanism, and a researcher at LabCidade FAU/USP. His work includes topics on self-management and collective property, as well as critical cartography and collective processes of territorial reading and planning.