This is Part 2 of a two-part article on the achievements of representation for Black Brazilian women at the 2024 Olympics.

The Olympic achievements of Beatriz Souza, Rebeca Andrade, Ana Patrícia Ramos, and Duda Lisboa are even more significant when considering the social context of Black women, plus-size women, and women from favelas, peripheral areas, or the northeastern region of Brazil in sports. For these groups, community organizations and public programs, when available, play a fundamental role in the development of residents from favelas and peripheral areas, contributing to the reduction of inequalities, social inclusion, and the promotion of fundamental rights.

These initiatives often emerge as a response to the State’s negligence in these regions, offering community-based alternatives that have the power to transform lives. The positive impacts of investing in sports go far beyond the short term, leaving a lasting legacy that shapes the future of young people and families, enabling those residents of favelas and Brazil’s peripheries with potential to rise to the level of Olympic athletes. By investing in talent that would otherwise be overlooked, social projects transform lives and strengthen society as a whole.

These three are not isolated cases. There are a vast number of Olympic medalists from Brazil’s favelas and marginalized peripheries who were shaped by community sports programs. Another emblematic example of an Olympic champion raised through a social project is Rafaela Silva, a Brazilian judoka from City of God (CDD), a favela in the West Zone of Rio. She won a bronze medal in the mixed team competition in Paris and a gold medal in Rio in 2016. Her victorious journey began at a sports initiative in City of God. Silva began her judo journey at the age of seven when her parents, Luiz Carlos and Zenilda Silva, enrolled her and her sister Raquel in the “Geraldo Project.” Led by coach Geraldo Bernardes, this project later joined forces with the Reação Institute, founded by former athlete Flávio Canto in 2003.

Bernardes believed that the girls could become international-level athletes, capable of representing Brazil in major competitions. And he was right. Rafaela Silva’s journey from City of God to the Olympic podium is proof that well-structured social projects involving sports can be a powerful tool for social change.

View this post on Instagram

In the city of Rio de Janeiro, Olympic Villages represent a successful public policy that promotes sports and public health. Despite their misleading name, these villages do not house athletes waiting to compete. Instead, they are a municipal project that began in the early 1980s, providing quality infrastructure in favelas and peripheral neighborhoods, along with social programs and development opportunities. These initiatives help reduce violence, promote health, and strengthen community bonds. Olympic athletes have also been developed in these spaces, such as the Mangueira Olympic Village, located in Rio’s traditional North Zone favela.

The Mangueira Institute for the Future, which manages the Mangueira Sports Reference Center, focuses on both educational and competitive sports, with sponsorship from the Rio de Janeiro State Department of Sports and Brazil’s oil company Petrobras through the Petrobras Social and Environmental Program. This training ground has produced athletes like Isaac Souza, a diver on the Brazilian national team and an eleven-time Brazilian champion, who qualified for the 2024 Paris Olympics, which would have been his second Olympic appearance. However, the Mangueira athlete suffered a tendon rupture that forced him to withdraw from the Paris Games.

View this post on Instagram

Like Souza, other athletes trained and developed by Mangueira have reached the pinnacle of their careers. In her fourth Olympic appearance (Athens 2004, London 2012, Rio 2016, and Paris 2024), Érika de Souza, born and raised in Palmares, Campo Grande, in Rio’s West Zone, was also propelled to success by Mangueira’s Olympic Village.

At the 2016 Rio Olympics, track athlete Fabiana Moraes competed in the 100m hurdles, and she wasn’t the only Mangueira representative: the North Zone favela had hoped to have eight athletes competing for Brazil. At the Tokyo 2021 Olympics, alongside Isaac Souza, two other Mangueira athletes were present: Natasha Rosa in weightlifting and Gabriel Constantino in the 110m hurdles.

It is important to remember that beyond the Olympics, the programs in Mangueira have also produced leading figures in soccer. Midfielder Philippe Coutinho, who started with Vasco da Gama in Rio and has played for major clubs worldwide, such as Internazionale Milano in Italy, Liverpool and Aston Villa in England, Barcelona in Spain, Bayern Munich in Germany, and Al-Duhail in Qatar, started his sports journey at Mangueira. This highlights that Mangueira is a breeding ground not only for great samba masters but also for top-tier athletes.

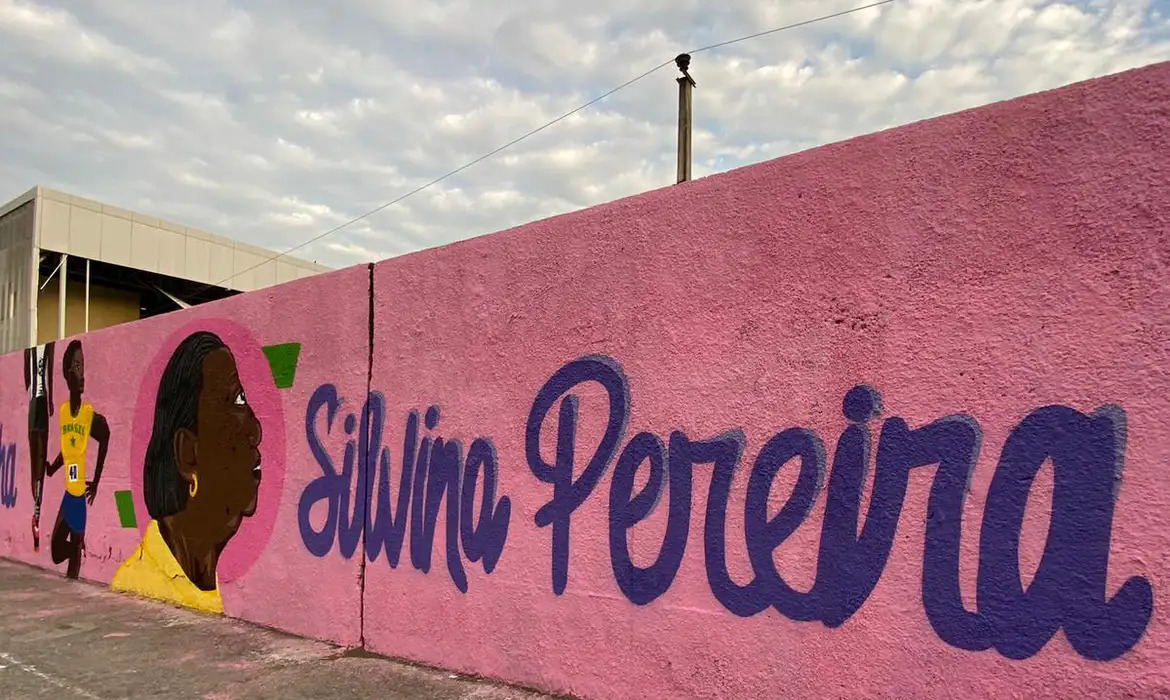

All of these success stories were only made possible because, in the 1970s, a Black woman from Mangueira blazed the trail to the Olympics. Silvina das Graças Pereira da Silva was part of the Brazilian team at the 1976 Montreal Olympics in Canada, competing in the long jump and 200-meter dash. Today, Pereira da Silva is immortalized alongside other Mangueira women in a graffiti mural in the community.

As we can see, sports in Mangueira have deep roots and have produced many champions. Among its rising stars for the future of Brazilian sports is Taiane Justino, a weightlifting athlete. Born and raised in Mangueira, she attended the 2024 Paris Olympics as part of the Brazilian Olympic Committee’s (COB) Olympic Experience Program, which brings young sports talents to the Games who may potentially compete for Brazil in the next Olympics.

In Paris 2024, many athletes from favelas and peripheral areas participated and brought pride to their communities, even without winning medals. In a viral video, Ygor Coelho, still a young boy dreaming of his Olympic participation in Paris, moved the Brazilian public. Despite competing in badminton, a sport with little tradition in Brazil, Coelho, born and raised in the favela of Chacrinha—situated in Rio’s West Zone between the neighborhoods of Praça Seca and Tanque, in Jacarepaguá—persisted and, for the third time, took part in the Olympic Games. His athletic training began at the age of three through the Miratus project, founded by his father, Sebastião Dias de Oliveira, in Chacrinha in 2000. Before France, he had already competed in Rio in 2016 and Tokyo in 2021.

View this post on Instagram

Like most of the athletes mentioned in this article, Gabriele Sousa dos Santos, a triple jump athlete from Santa Cruz, is the product of a community organization’s sports programs. However, after not qualifying and finishing 27th in the triple jump at the 2024 Paris Olympics, the athlete challenged the concept of defeat in an interview. For her, the very presence of favela-raised athletes in this competition is already a victory in itself.

“I’m so happy to be here, it’s my first Olympic Games! The girl who started running in the favela in Rio de Janeiro could never have imagined she’d be here, you know? It’s not just about winning or losing a medal, the Olympics… I’ve overcome a lot to be here. I’m already a winner just by being here. I’m representing an entire generation of girls, of children, who started in track with me, and many got lost along the way. I represent my family, my friends, I’m representing so many people, so, did I really lose?”

Another athlete supported by public policies was Laura Amaro, born and raised in Cascadura, a neighborhood in Rio’s North Zone. The “real Rio deal,” as she describes herself, began her athletic career early through a social project at the Almirante Adalberto Nunes Physical Education Center (CEFAN) in Penha, offered by the Brazilian Navy. At the age of 13, she joined the Forces in Sports Program (PROFESP), where she began high-level weightlifting training, which ultimately led her to the Paris Olympics.

It is worth highlighting the impact of this and other public policies by the Navy aimed at investing in sports. At the 2024 Paris Olympics, they comprised 30% of Brazil’s athletes.

A native of the Greater Rio metropolitan region, Mariane Fernandes, 28, is a left back for the Brazilian national handball team and is participating in her first Olympics. Born in Rio’s sister city across the Guanabara Bay, Niterói, and raised in a favela in the Anchieta neighborhood of Rio’s North Zone, she feels like she’s living a dream simply by representing Brazil.

“Every time I put on the Brazilian national team jersey, I feel like I’m living my dream… The 13-year-old Mariane, when she first started playing handball, never imagined how much of the world she would get to see… she dreamed, but it seemed like such a distant possibility, and yet, dreams do come true.”

Fernandes began her handball journey in the neighboring city of São João de Meriti, in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region, during her early teens. At 16, she received an invitation to play for the Methodist Sports and Cultural Association handball club, based in São Bernardo do Campo, in the interior of São Paulo.

Recently, a video of Fernandes, speaking emotionally and proudly of her journey and background, went viral on social media. The video was recorded as soon as she arrived at the Olympic Village in Paris. In it, she reflected on her life as an athlete from the favela and called on authorities to pay attention to favelas and favela talents, who have been historically neglected.

View this post on Instagram

DE ANCHIETA PARA O MUNDO!

A Mariane Fernandes, da seleção brasileira de handebol e cria de Anchieta, no Rio de Janeiro, mandou o papo: a comunidade exala talento!

Você é gigante, Mari! Do tamanho dos seus sonhos! #Paris2024 #JogosOlímpicos #TimeBrasil pic.twitter.com/RTpubxu27L

— Time Brasil (@timebrasil) July 24, 2024</a

Highly notable athletes at the 2024 Olympics, brothers Darlan and Alan Souza of the Brazilian volleyball team, hail from Nilópolis, a municipality in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region. Both play as opposites, a position responsible for scoring points and making key plays during the most crucial and tense moments of the game. Alan Souza, 29, is an inspiration to his younger brother, who has followed in his footsteps.

“My biggest role model in sports is my brother [Alan]… He went through certain situations… To be able to train, he had to collect soda cans. He needed the money to take the train and go to practice. So having someone who achieved their dream and comes from the same place as you is incredibly motivating… you know what he went through, you saw his journey, the obstacles he overcame. For me, there is no greater or bigger idol than my brother.” — Darlan Souza

Alan Souza began his volleyball journey at the age of 14, playing at the Maria da Conceição Cardoso Municipal School in Nilópolis. A thoughtful and intelligent student, his physical education teacher saw potential in him for volleyball. Teacher Xandão noted that forming a volleyball team at the school might interest the students, but he didn’t expect the team to be so competitive. The school went on to win third place in the Student Games—an inter-school state tournament.

With this, other coaches in the region began to recognize Alan Souza’s potential, and an opportunity arose for him to join the Nilópolis regional team in a championship against neighboring cities in the Baixada. Despite not playing his best game, a coach and scout from the Botafogo sports club—located in Rio de Janeiro’s South Zone—saw him play and invited him to join the team. As financial constraints and distance would be obstacles, the club provided him with a stipend to help cover costs.

In less than two years of playing volleyball, Souza was selected for the Rio de Janeiro state team, which would compete in a national championship. Shortly after, he was invited to join the Brazilian national team training at the Brazilian Volleyball Confederation’s (CBV) Saquarema Training Center. At 17, Alan Souza was signed by Cruzeiro and moved to Belo Horizonte, capital of the state of Minas Gerais. After leaving Cruzeiro, he played in states across Brazil, as well as in Russia and Poland.

Meanwhile, his younger brother, Darlan Souza, 21, is a substitute for his older brother on the national team and has had the opportunity to play due to Alan’s injury and subsequent rest. Darlan is a big fan of Naruto and gained fame on the Internet for his ‘jutsu’ celebrations, hand movements inspired by the Japanese anime. A key player on the national team, Darlan Souza played a major role in their successful pre-Olympic campaign and was crucial in the Brazilian men’s team’s Olympic journey. In his Olympic debut, despite a loss to Italy, he was the top scorer of the match, single-handedly contributing 25 points.

In an appearance on the Ubuntu Sports Club podcast, Darlan Souza spoke about his journey and the importance of his family’s support, especially his mother’s, and the bond with his brothers. He also highlighted the crucial role that the AN2 Volleyball School, run by instructor Miúdo in Nilópolis, played in his athletic development and that of his brothers. After months of training, his coach arranged a high-level training opportunity in another city and neighborhood far from his home. However, this opportunity came with numerous obstacles. He discussed the challenges he faced as a resident of the Baixada Fluminense and the foundations of his success.

“My coach arranged a tryout for me at the Banco do Brasil Athletic Association (AABB) on the Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon [in the heart of Rio’s wealthy South Zone]. I managed to pass, and my mom came along with me. That’s when my life started… From Nilópolis to Lagoa is quite a distance. Since I live in the Baixada, neither my family nor I knew how to navigate down there, as we say, around the South Zone. I remember that at first it was complicated, we weren’t sure how to get there. I live about 20 minutes from the Nilópolis train station, so I would walk there, take the train to the Central do Brasil station, and then catch a bus that went near AABB, but it went around in circles. It took about two hours to get to the club… Later, my coach taught me a different route. I’d take the train to São Cristóvão, then catch the 460 bus, which dropped me in front of [the] Flamengo [sports club] and AABB was right next to it… Before that, I wasted a lot of time. Training ended around 7 or 8pm, and I’d get home very late, but often at the beginning, my mom would go with me. That made me feel more at ease, it was comforting… When I left AABB, I played for Flamengo for a year. Then, I switched to Fluminense [sports club]… but I think one of the things that helped me a lot was my mom. Training started at 8pm at Fluminense and finished very late, around 9:30 or 10pm. I got home very late, midnight at the earliest. And every day my mom was there, sitting outside [the house], waiting for me… Every time I came back from training, she was there waiting. She would see me from the corner and then go make my dinner. It was surreal; my mom is one of the people who supported me the most. There were days when we didn’t have much, so often she would give me the meat and go without it. Many times, she didn’t have much to cook, but she would make a rice and egg dish with all the love in the world, and it was amazing to me. It’s these little things, which are not really little, that motivate you a lot, you know? A lot of who I am and what I have, I owe to my mom.” — Darlan Souza

Unfortunately, the Brazilian men’s volleyball team did not win a medal and was eliminated by the United States in the quarterfinals. Nonetheless, Darlan’s participation in the Olympics is a cause for celebration among all Brazilian volleyball fans.

https://www.tiktok.com/@sportv/video/7286268821348879621?is_from_webapp=1&sender_device=pc

Still on the outskirts of the metropolis, residents of Itaboraí, a municipality in Greater Rio‘s Eastern Region located on the other side of the Guanabara Bay, have been able to train in high-level Taekwondo since 2011. Thanks to the Diego Taekwondo Team social project, young athletes have been developed despite limited resources and have competed in various national and international championships. In 2024, the project excelled by qualifying three students for the Paris 2024 Olympics. One of them, fighter Edival Pontes, known as “Netinho,” who had previously competed in the Tokyo 2021 Olympics, won a bronze medal for Brazil in Paris. Born in the northeastern state of Paraíba, he moved to Rio de Janeiro to train with the Itaboraí team. He recalls that in his home state, there wasn’t even a mat available for training.

View this post on Instagram

On the same Brazilian team as the Olympic medalist, two other athletes from the social project also competed in France: Henrique Marques, from Vila Portuense, the more modest area of Porto das Caixas in Itaboraí, and Milena Titoneli, from São Paulo, who moved to Greater Rio’s Eastern Region to train for her second Olympic appearance. Neither of them won medals in Paris.

As seen, favelas are powerful in many ways, including in sports. The legacy of athletes like Bia Souza, Rebeca Andrade, Duda Lisboa, Ana Patrícia, and many other pioneering Black, favela, and peripheral athletes, has been remarkable. Brazil has witnessed Black excellence across various sports disciplines. This serves as a powerful reminder that, with the necessary support, Black individuals and favela residents are valuable assets to the entire country. By breaking barriers in sports historically dominated by white individuals—such as judo, skateboarding, beach volleyball, and gymnastics—these athletes demonstrate that, with or without medals, they are worthy of a space on Olympus.

This is the second part of a two-part article on the achievements of representation at the 2024 Olympics. Click here for Part 1.

About the author: Julio Santos Filho has a Bachelor’s in International Relations (UFF) and a Master’s in Sociology (IESP-UERJ). A Black man from Ilha do Governador, he has worked as editor of RioOnWatch since 2020. In 2021, he edited the series “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas”, a silver medalist in The Anthem Awards.