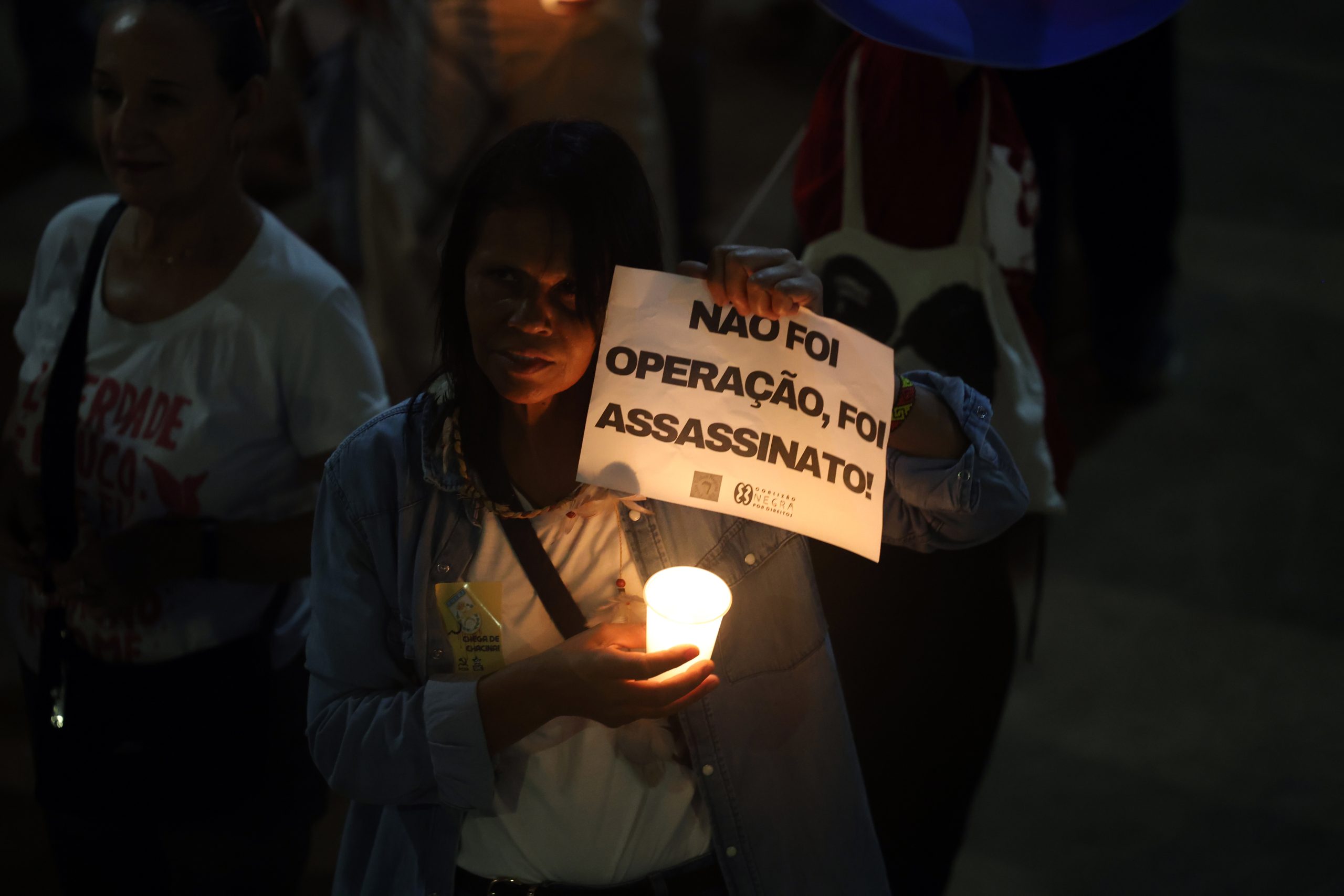

In the early morning of October 28, 2025, 2,500 Civil Police and Military Police officers entered the Penha and Alemão favela complexes for a mega-operation that became the deadliest in the history of Rio de Janeiro and Brazil. The next day, when State agents exited these favelas, they left behind at least 121 people dead. Here we share some of the feelings experienced by those who remain. Walking through the streets of the two favelas, tension remains in the air.

“The mood [here] is one of profound grief and heavy silence. There is sadness, there is anger and there is a very clear sense of injustice. The favela is experiencing collective mourning, but it’s also experiencing what it always experiences: the need to move on, even while wounded, because daily life doesn’t wait. Deep down, the feeling is that life here is never truly treated as life and that hurts more than anything.” — Raull Santiago from the Straight Talk Institute

According to residents like Fabrício Motta, who lives and works in Complexo do Alemão, once the noise from the helicopters and armored vehicles stopped, the State’s silence echoed.

“We haven’t seen any public services come in since last week. Once again, it’s the favela rebuilding what the State destroyed.” — Fabrício Motta, Complexo do Alemão resident

Businesses, schools, health centers and transportation are operating again in both favela complexes. However, no one speaks of a return to “normal life.”

“There’s no such thing as normal after a massacre. The streets function, but the hearts of the people remain heavy. The city returns, but the favela goes on with its body and soul scarred.” — Raull Santiago

Similarly, Beatriz Costa, a resident of Complexo da Penha, says nothing can feel right after 121 people were murdered in the streets and wooded areas of her neighborhood.

“We go back to doing [things], to working, to taking the kids to school, because there’s no other way. But things are not fine at all!” — Beatriz Costa

Amid this grief, fear, outrage and helplessness, support comes from the favela itself, from social organizations and social movements.

“The State comes in to kill, but it doesn’t come in to care, investigate, repair, or support. This needs to be said: those who experience State violence have to beg for attention afterwards… [but] I believe [in change] because I work towards it. Because the favela never gave up on Brazil, even when Brazil gives up on the favela. But change won’t come on its own. It comes with pressure, with real public policy, with respect for life, with education, with technology, with jobs, with opportunity, with listening to the favela and with the courage to break with this war-driven model. Public security isn’t an armored vehicle, it’s the future. And the favela has a future to offer, if they would just let us live.” — Raull Santiago

About the author: Felipe Lucena is a journalist, columnist and screenwriter. The son of migrants from Brazil’s Northeastern region and raised in Curicica, in Rio’s West Zone, he is currently a special reporter for online newspaper Diário do Rio and also contributes to other news outlets.