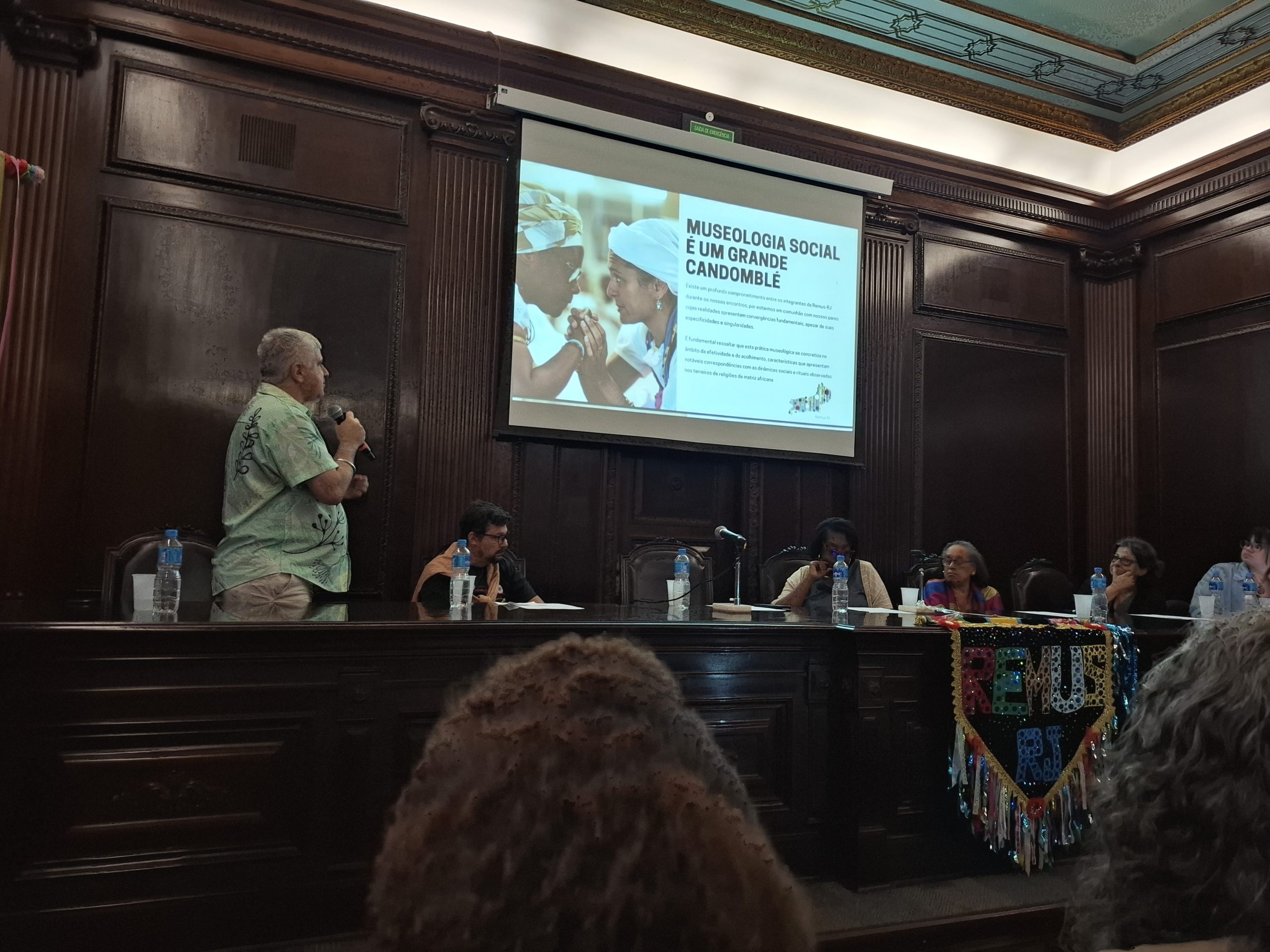

On Saturday, May 16, Rio de Janeiro’s renowned Banco do Brasil Cultural Center (CCBB) hosted several institutions involved with museology—including community museums, memory collectives, and projects focused on social memory—alongside researchers, for the 1st Social Museology Seminar of the Rio de Janeiro Social Museology Network (REMUS-RJ). The event’s primary objective was to foster discussions around “unconventional” museums.

This first-of-its-kind event was guided by the theme: “Solidarity and Affection Aligned with Life – A Meeting of Communities and Museums: Democracy and Museology that Serve Life Transform the World.” It was part of the Brazilian Institute of Museums’ (IBRAM) 23rd National Museum Week, held from May 12 to 18, whose overarching theme was “The Future of Museums in Rapidly Changing Communities.”

Sarah Braga, vice-president of the International Movement for a New Museology (MINOM), coordinator of REMUS-RJ, and museologist at CCBB-RJ, opened the seminar by outlining the goals of the Social Museology Network and the intentions behind the gathering, shaped by extensive discussions among member institutions about the themes to be presented.

“The State of Rio de Janeiro’s Social Museology Network aims to connect and promote the exchange of experiences and knowledge, cooperation, and collective actions among the various initiatives included within the range of social museology and spread throughout the state. By amplifying the voice and strength of each initiative within it, we share in the understanding that strengthening others is also a way of strengthening ourselves, and believe in memory and resistance as forms of liberation, change, and transformation of reality.” — Sarah Braga, International Movement for a New Museology

Next, the opening panel “Social Museology: The Ancestral Future of Museums” brought together influential voices in the field: Mário Chagas, professor at the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro (UNIRIO), the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), and the Lusófona University of Lisbon, former director of Rio’s Museum of the Republic, and coordinator of REMUS-RJ; Cláudia Rose, coordinator of the Maré Museum, member of the REMUS-RJ coordination group and the Advisory Board of Casa de Oswaldo Cruz (part of Brazil’s national public health foundation, Fiocruz); and Sandra Teixeira, co-founder and co-manager of the Evictions Museum in Vila Autódromo, in Rio’s West Zone. Together, they presented an overview of the development of Brazil’s national museum policy, the role of social museums within it, and the relationship between political discourse and current practices in the field of social museology, based on the actions and experiences of individuals working in spaces dedicated to memory preservation.

“The archive is the soul of the Maré Museum, and the exhibition is its heart. The entire museum is a living body—that beats and has its own will. We often want one thing, and the museum wants another. The soul of the museum is ancestral: it’s the archive of Dona Orosina, a Black woman, a migrant, who arrived poor at Rio’s Central [train] Station… She started going to Maré in the 1940s, taking her husband there to breathe fresh air. She fell in love with the place and built a shack using scraps of wood she found nearby. She was one of Maré’s first residents. That is why the Dona Orosina Archive is soul, ancestrality. We welcome each new activity, each group of visitors with open arms and with the vigor of a future rooted in ancestral knowledge.” — Cláudia Rose, Maré Museum

“When we thought about creating the Evictions Museum, we understood that this wasn’t the kind of museology we were used to. This is a museology of struggle—a museum that speaks of life and social change. It’s a museology rooted in resistance. A museology rooted in life.” — Sandra Teixeira, Evictions Museum

Lunch was followed by the first panel, “Discursive Democracy, Racism, and LGBTphobia: The New Face of Brazil’s National Museum Policy.” Once again, the discussion featured museums that are part of REMUS-RJ: Antonia Ferreira Soares, general director of the Favela Museum in the Pavão-Pavãozinho and Cantagalo favelas; Antônio Carlos Vieira, director of the Maré Museum in Complexo da Maré; Emília Maria de Souza, director and co-founder of the Horto Museum in the Horto community; Marco Antônio Teobaldo, curator of the Iyá Davina Memorial Museum in São João de Meriti, which is dedicated to the history of the Afro-Brazilian religion of Candomblé; Marlucia Santos de Souza, director of the São Bento Living Museum in Duque de Caxias; and Master Paulão Kikongo, a doctoral student in Social Memory at UNIRIO and director of the Iê Living Museum of Capoeira Art and Culture in Guapimirim. The last three museums are located in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region.

The panelists, all from community museums across the state’s favelas and peripheries, discussed the challenges of acquiring and maintaining the properties where these museums are located, the lack of support and investment from the City of Rio for cultural spaces in peripheral areas, and the violence present in some regions. They also addressed the impact of real estate speculation, which threatens memory and cultural centers. Lastly, they pointed to the need for a legal instrument that guarantees the right to preserve memory and sustain cultural initiatives developed by these museums, so they are not undermined by real estate interests or arbitrary policies.

“Public policies are defined by public officials inside offices and don’t consult those they like to call ‘needy.’ They implement policies without understanding the work the community is already doing for local development. We are a favela museum. Our collection is the people. So we need to take care of our people. We do not have the resources to carry out our activities. Everything we do comes at great sacrifice.” — Antonia Ferreira Soares, Favela Museum

Master Paulão Kikongo also emphasized the need for individuals involved in social museology to be included in discussions around public policy and decision-making. “We do everything in a circle: samba, capoeira, gira… The only thing that doesn’t circulate among us is money,” he added.

The second panel, “Social Museology in Movement: Grassroots Communities, Knowledge, and Ancestral Technologies in Confronting Contemporary Emergencies,” featured: Alexandre de Nadal Arantes, communications director at the Pretos Novos Institute, in Gamboa; Magali Cunha, professor and journalist; Candomblé Priestess Flávia da Silva Pinto, religious minister of Umbanda and Candomblé Ketu and founder of the Olga do Alaketu Living Museum in Greater Rio’s Seropédica; Jandira Rocha de Oliveira, coordinator of the Agroecology Living Museum; and Candomblé Priest Paulo José dos Reis, from the Bongaba Quilombo. The last two panelists are from Magé, in the Baixada Fluminense.

During this session, participants reflected on the role of social museology and its various expressions in combating misinformation and promoting what was referred to as “cognitive freedom.” These museum spaces work to preserve the areas and cultures of people who have long been excluded from hegemonic narratives—especially Black and indigenous populations. Magali Cunha described this as a form of cognitive shielding that misinforms, stigmatizes, and devalues expressions of grassroots and peripheral culture, preventing broader recognition of the importance of preserving these practices. Mother Flávia called for greater dialogue between social museology and conventional museums as a way to dismantle the colonization of knowledge and memory. Father Paulo emphasized the agency of traditional communities, which develop strategies to confront structural racism while safeguarding their memory.

“Traditional communities—both quilombola [settlements that can trace their occupation by Black Brazilians dating back to slavery] and of African religious origin—carry an added burden on top of what we call prejudice and structural racism. To combat this prejudice and racism, we have built the deconstruction of the hegemonic and negative view of our deities and of the quilombola system. To do this, we break through the cognitive shielding that once determined where we would be and who we would be—so that we can instead embrace cognitive freedom, which tells us that our place is wherever we want to be.” — Father Paulo, Bongaba Quilombo

Several statements took a stand on the importance of social museology in tackling issues such as food insecurity, gender violence, racism and environmental disasters.

“Most people who seek out the terreiros [Afro-Brazilian places of religious worship] are women. Most people who seek out religion are women. I belong to one of the few religions in the world where women are the authority. It was one of the few that preserved this sacred, ancestral feminine. Today, people speak of ancestrality as something mythical, but ancestrality used to be political. It was matriarchal leadership that decided questions of justice, food distribution, food security. By keeping this vision of matriarchy alive, the museum will tell many stories: it will speak of the genocide of the Black population, of food sovereignty, and of the orixás’ [Candomblé deities] worldview as a process of healing. It will also tell how the creation of the terreiros is what ensured the survival of the Black population. It is what made it possible for us to be here today, speaking.” — Mother Flávia, Olga do Alaketu Living Museum

The seminar came to a poetic close. Carrying banners with slogans like “Only Poetry Can Save Us,” members of the State of Rio de Janeiro’s Social Museology Network and audience members descended the steps of the CCBB singing one of singer-songwriter Gonzaguinha’s most iconic songs. Mário Chagas led the chorus:

“To live and not be ashamed of being happy,

To sing and sing and sing about the beauty of being an eternal learner,

I know that life should be much better… and it will be!

But that doesn’t stop me from repeating:

Life is beautiful, it is beautiful, it’s beautiful!”

The singing and banners caught the attention of those at the CCBB, a key cultural space in Rio’s downtown. From time to time, the chorus was interrupted by powerful slogans. And then, the phrase heard again and again throughout the seminar finally echoed through the entire Banco do Brasil Cultural Center: “A Museology That Doesn’t Serve Life Serves No Purpose.”

On the ground floor, a jongo circle led by the Bongaba Quilombo awaited the procession. The event ended with a shared sense among those present: that social museology serves the lives of those who defend memory, grounded in the certainty of a better future.

“I represented the Indiana favela in Tijuca and the Memories Museum of the Indiana Favela of Tijuca (MEMOCIT). I had a very good experience at the seminar because it dealt with social museums. We don’t have full access to museums that have an official seal and all that structure. So, by holding this seminar, REMUS-RJ gave social museology the opportunity to be inside a renowned space, the Banco do Brasil Cultural Center. We were treated well and felt welcomed. We were able to talk about our anxieties, victories, and outlooks regarding the future of our projects. It was great! I felt invigorated—and I say that with confidence. If I had any difficulty trying to move MEMOCIT forward, I don’t anymore. Because now I know it’s possible for us to occupy these spaces and have a voice, our turn, and participation.”

— Marcello Deodoro, Memories Museum of the Indiana Favela of Tijuca

About the author: Bárbara Nascimento was born and raised in Vidigal. A Portuguese teacher in the Rio de Janeiro city and state public school systems, she holds an undergraduate degree in Modern Languages (from UFRJ in 2002) and a Master’s in Social Memory (from UNIRIO in 2019). She founded and directs the Vidigal Memories Nucleus, archiving and recording the collective memory of Vidigal.