Clique aqui para Português

This article is part of a series created in partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University, to produce articles for the Digital Brazil Project on environmental justice in the favelas for RioOnWatch.

This article is part of a series created in partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University, to produce articles for the Digital Brazil Project on environmental justice in the favelas for RioOnWatch.

In the Rio de Janeiro metropolitan region, residents of favelas and peripheral areas in the municipality of São Gonçalo—located in the Leste Fluminense region, across Guanabara Bay from Rio proper—face precarious and challenging living conditions. Seeking to transform this reality, a group of women from Jardim Catarina, Itaoca, and Complexo do Salgueiro have been developing initiatives to promote environmental and climate justice, gender literacy, women’s empowerment, and the creation of job and income opportunities for women in these favelas and surrounding areas.

Founder and executive director of the organization, Laura Torres shared that Gaia Space currently supports 110 children and 80 women—15 of whom are pregnant. Laura is from the favela of Jardim Catarina, but has been working in neighboring Complexo do Salgueiro since 2022.

“Gaia Space is a place for empowerment and emancipation within Complexo do Salgueiro. It’s an organization made up of women from São Gonçalo.” — Laura Torres

Among the initiatives already developed by Gaia Space are actions aimed at promoting women’s participation in society, fostering gender literacy, ensuring food security through a community garden and an agroforestry course, generating income opportunities with courses on braiding and ceramics, and producing data on environmental racism and the impacts of climate change. One of Gaia Space’s efforts involves monitoring flood-prone areas within Complexo do Salgueiro and informing residents through a messaging app group.

“We define ourselves as a civil society organization working with gender and climate. These are our two main causes. Within them, we understand it’s essential to talk about race and class—because we’re inside a favela, in a sacrifice zone, near what used to be a garbage dump. Most of the residents are women and, obviously, they are Black, brown, and have had little access to education. And that also ends up affecting how much income they are able to generate.” — Laura Torres

According to Torres, 50 of the women participating in Gaia Space’s projects live in the Itaoca favela, near the former garbage dump—located between a road, Estrada de Itaoca, and the Fazenda dos Mineiros neighborhood, cutting through Complexo do Salgueiro. When the Itaoca dump was shut down in 2012, in accordance with the solid waste law, the women from the area who worked as recyclable material collectors were left with nowhere to go—and no way to make a living.

“They didn’t receive any compensation, unlike [the recyclable material collectors from] the Jardim Gramacho landfill. There was no such compensation given, here in São Gonçalo. These people never saw a penny. And that ends up affecting everything that followed after the closing of the old dump—there are social and economic consequences.” — Laura Torres

Many women from the Itaoca favela who are supported by Gaia Space were directly affected by the closure of the dump. One of them is Flaviele Souza Cruz, 32, a mother of four who lives with her family in Complexo do Salgueiro. She has been participating in Gaia Space projects since 2023.

“It was the only income we had. When the dump shut down, just like that, without [the government] offering any support to the people who worked there, we were left with no options. Nothing to rely on. So, to this day, many women still collect recyclable materials, try to get some cleaning work… But it’s also hard to find a job these days, because the women who hire them don’t want to register domestic workers formally.” — Flaviele Cruz

She mentioned that the closure of the Itaoca informal landfill also affected the health and food security of the former waste pickers.

“A lot of people used the money they made from the dump to buy medicine and food—on top of what we actually got from there. I’m not gonna lie and say we didn’t eat things that came from the dump, because we did. We made use of a lot of food that was still good to eat.” — Flaviele Cruz

Gaia Space was created, initially, to offer obstetric violence awareness training to the local population. According to Torres, it was the first community project to work towards emancipation and break away from welfare assistance devoid of a grassroots approach. With time, its founders identified other community needs that had to be discussed and addressed.

“I’d lay out a sarong under a tree and gather with people to talk about obstetric violence. A friend of mine had a few stools and we’d sit in a circle to talk. After a year, more or less, we were able to establish our headquarters. We deal with everything, from domestic violence cases to people who have nothing to eat.” — Laura Torres

In pursuit of its mission to promote rights in the community, the organization created the Keeping an Eye on Itaoca Observatory. With support from local residents, the Observatory conducts research to map community needs, aiming to influence public policies.

“Last year, we published a report on socioenvironmental monitoring. Fighting for public policies is much more tangible when you have data to back you up.” — Laura Torres

Of the 42 households surveyed, 32 interviews were successfully recorded. Among the interviewees, 75% are women and 81.3% of them are Black. When it comes to sanitation, 78.1% of those interviewed do not have access to piped sewage, and 92.9% of those without sewage treatment are Black. In addition, 28.1% of households do not have a toilet. As for water access, 75% of households either lack running water or the water available is not potable, and 78.1% rely on communal taps. With regard to waste, 90.6% of households burn their garbage due to the absence of municipal garbage collection services.

Additionally, the organization is developing a study on the care economy and environmental racism with 100 women—including residents supported by Gaia Space and others living near the former Itaoca landfill—in partnership with La Poderosa, a civil society organization from Argentina. The idea for this monitoring effort came out of conversations with the pregnant women in the project.

“We did a study to understand what life is like for the women who live in Complexo do Salgueiro, particularly when it comes to what we call the care economy—those day to day tasks like looking after the house, the kids, the elderly, all of the responsibilities that almost always fall on women. We wanted to understand how the basic lack of infrastructure in the community—like lack of water, trouble getting a spot in daycare, bad transportation, or transport that never even shows up—upends their routines and messes with their mental and emotional health.” — Laura Torres

One of the findings from this new study reveals the difficulty of accessing public transportation, which can, in turn, make it harder for women to access health centers or for their children to get to daycare. According to Torres, 65% of the women interviewed said it takes them over 15 minutes on foot to reach the bus stop. Regarding transportation costs, fares can consume up to 25% of the income of those living in the area. Another problem is access to water: over half of the population faces water shortages and, of those affected, 80% are women. Among these women, almost 43% said they go out alone to fetch water.

In addition to this initiative, Gaia Space is developing the Agenda to Resurrect São Gonçalo. As a response to the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda—which sets goals to ensure social and environmental justice for the global population by 2030—the Agenda is part of a broader movement of 2030 Community Agendas that, according to Gaia Space, “collect each area’s real priorities, showing what needs to be done there, based on the lived experiences of those who build the everyday life of that place.”

Developed in conjunction with other movements and collectives from São Gonçalo, the Agenda to Resurrect São Gonçalo brings together demands from the seven favelas that make up Complexo do Salgueiro—ranging from sanitation and transportation to health, education, and climate justice—to be delivered to the São Gonçalo City Council and City Hall in July of this year. The goal is to identify the gaps in access to basic rights and to propose new strategies to ensure those rights are fulfilled.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

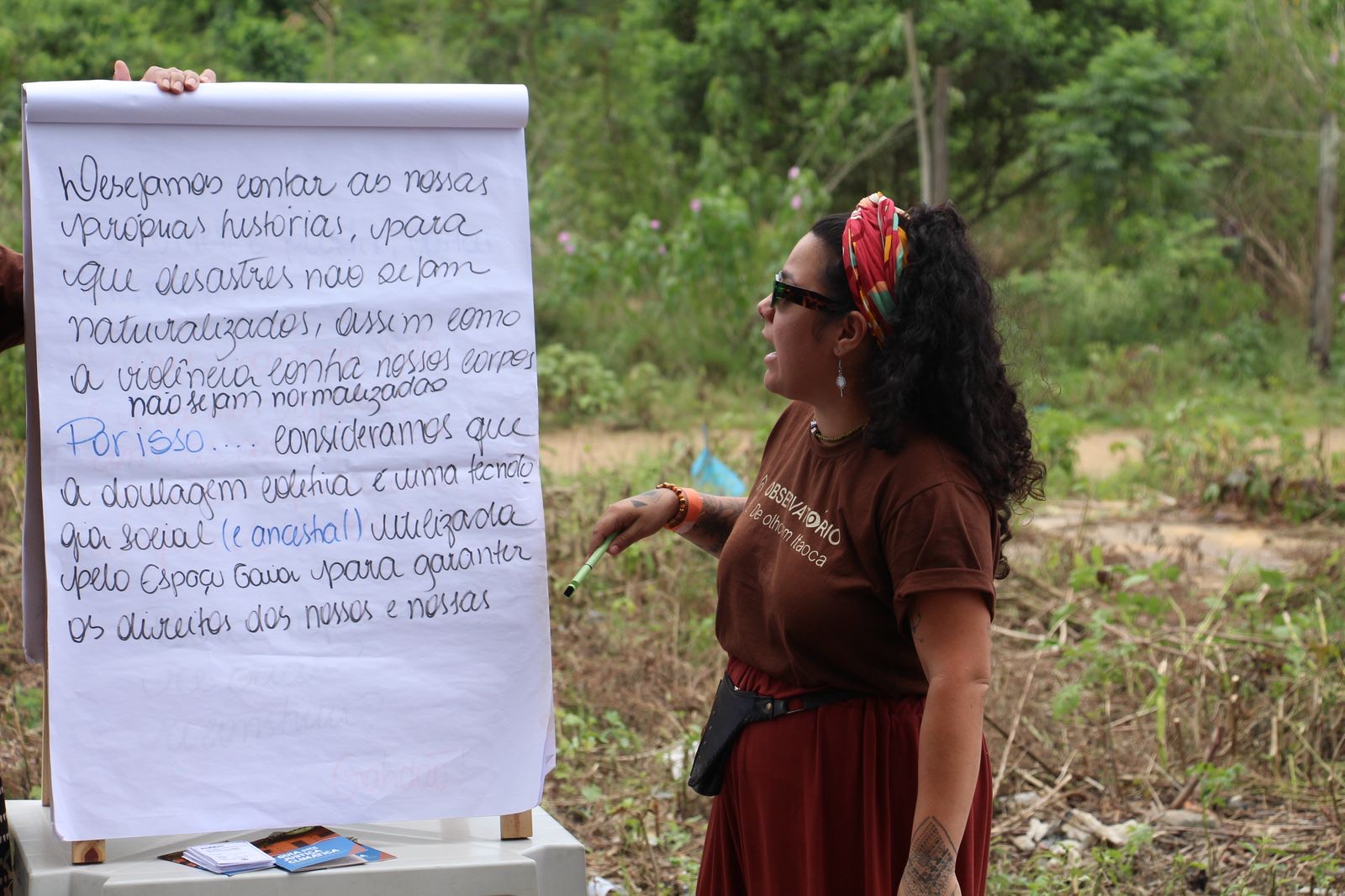

“In this monitoring report, we discuss, for example, some social and ancestral strategies created by residents to survive in the community,” said Torres, who mentioned collective doula care as one of these strategies—used to support pregnant women in the community, both before and after childbirth.

Bruna Oliveira, 33, is a self-employed mother of three and a resident of Complexo do Salgueiro. She became aware of the importance of environmental issues during her brief participation in the collective doulas project.

“There [at Gaia Space], there was a course I didn’t take part in, but from the little I saw, it was really great. The girls planted, harvested, and brought the food home for their daily meals. It was really good—even for the kids who went with their moms—because they learned how to eat healthy, they learned what it means to grow your own food.” — Bruna Oliveira

Gaia Space also offered agroforestry training to women in the community, who learned how to grow parsley, basil, tomatoes, sugarcane, and other vegetables and greens. The need for this initiative emerged after the organization identified nutritional deficiencies among children in Complexo do Salgueiro. Although the project is key to promoting healthier living in the community, it has been on hold since Gaia Space relocated in December 2024. Despite the challenges, project members hope to resume the community gardens soon. They are currently seeking funding opportunities and have launched a crowdfunding campaign to purchase a new space where they can carry out their work.

“[Agroforestry training] serves as nutritional support. We understand the need to think about fruits and vegetables, which are expensive. The course was meant to give women access to healthier fruits, vegetables, and greens—without pesticides. And the idea behind the course was to promote environmental awareness among them. So we talked about environmental racism, we talked about the mangroves in the area.” — Laura Torres

With the goal of broadening the discussion and influencing safety policies for pregnant women, Gaia Space runs the Cycles Program—a discussion circle held every six months, offering collective doula care for expectant mothers. It also promotes the Circle for Pregnant Women, which fosters the exchange of knowledge about motherhood among women in the group of favelas, including guidance on childbirth.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

“We used to get a lot of obstetric violence cases—cases where a partner wasn’t allowed in because hospital staff wouldn’t let him. Cases of pushing on the belly and cutting. I’d take all these complaints, send them to the government, and they’d carry out inspections at the maternity hospital. That’s how we managed to get some really important things [for the hospital], like a mortuary chamber and an autoclave.” — Laura Torres

Torres stated that some of the organization’s initiatives have already prompted responses from the government regarding what they classify as obstetric violence. According to her, following a complaint filed with São Gonçalo’s City Council, equipment was installed at the Mário Niajar Municipal Maternity Hospital.

For Cruz, Gaia Space is, more than anything, a place for knowledge exchange.

“The project has been a big help to me and to many other mothers here in Salgueiro. It teaches us a lot—how to handle situations that used to make us panic. But these days, we take a deep breath and talk things through. It’s not just for food [that the organization is here], it’s about helping us understand our rights, talk, and open up about what we’re feeling.” — Flaviele Cruz

Oliveira also recalled when she first came across the project, and how important these women were in supporting her through a period of depression during her pregnancy.

“I was six months pregnant, going through a period of depression because I had just lost my mother and had been fired [from work] while pregnant. I didn’t know my rights. Thanks to Gaia, I know them now.” — Bruna Oliveira

According to Torres, the goal is to replicate the strategies imagined and practiced by Gaia Space in other favelas across Rio de Janeiro, since “we understand that [the initiatives carried out by Gaia Space] are not a need exclusive to Complexo do Salgueiro.” The members’ wish is that, in all favelas, mothers can count on a support network as diverse, flexible, and resilient as the one Gaia Space provides to mothers in Itaoca, Jardim Catarina, and Complexo do Salgueiro.

About the author: Igor Soares was born and raised in Morro do Borel and has a journalism degree from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). He currently contributes to #Colabora and works as a freelancer. He has experience covering topics related to cities, human rights, and public security, having previously worked at Estadão, Portal iG, and produced reports for Folha de São Paulo.