“There’s a total lack of transparency on the part of the authorities with Colônia and its residents. We want answers,” asserts Juliana Moura Marques, resident of Colônia Juliano Moreira in Jacarepaguá and member of the community’s E-Colônia movement.

For the last few months, the group has been calling for explanations from the City government over the change in route of the TransOlímpica BRT highway to pass through the neighborhood, abandoned public works and the proposed use of the community’s historic psychiatric hospital for the compulsory treatment of crack addicts. They organized a meeting for this purpose on Friday March 22nd, yet no one from the City attended or informed to say they wouldn’t attend, leaving the 150 frustrated residents in attendance still without answers.

Above all, residents want to know definitively whether rumors of dramatic government interventions in their community are really what the future holds for this hidden and little understood corner of the city.

History of Colônia Juliano Moreira

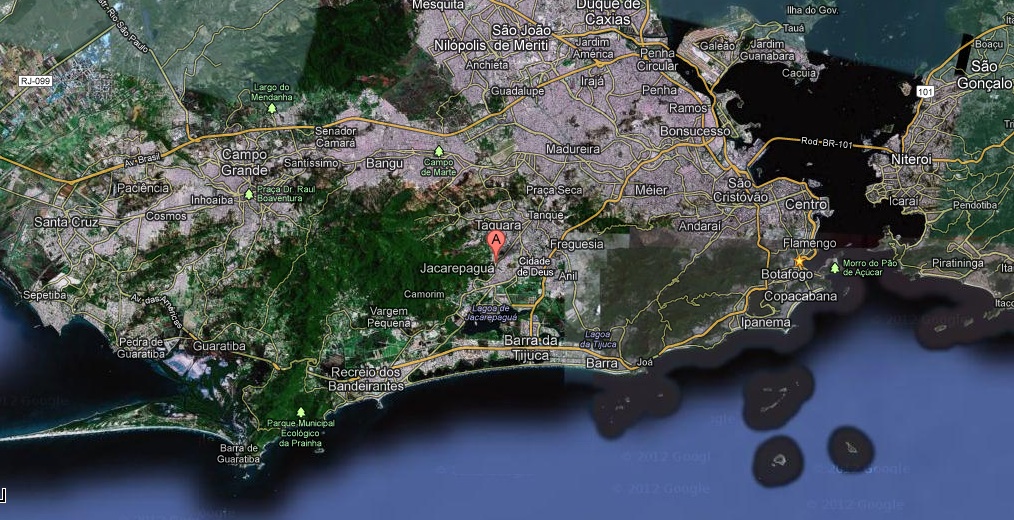

Colônia Juliano Moreira is a unique place. Set on the fringes of the Pedra Branca State Park, the vast 78km2 area is most famous for the psychiatric hospital around which the neighborhood has grown (see map below). Formerly a sugar mill, the area was disappropriated by the federal government in 1912 and the psychiatric insitition established in the following decade to which patients from the existing facility in Ilha do Governador were transferred. The West Zone location was chosen for it’s isolation from Rio’s urban center and lush forest and green areas, as the medical thinking of the time was that psychiatric patients should have contact with nature. The institution built houses for workers on the enormous grounds, which was renamed Colônia Juliano Moreira in 1935 after the recently deceased doctor known for his humanized treatment of patients.

Colônia Juliano Moreira is a unique place. Set on the fringes of the Pedra Branca State Park, the vast 78km2 area is most famous for the psychiatric hospital around which the neighborhood has grown (see map below). Formerly a sugar mill, the area was disappropriated by the federal government in 1912 and the psychiatric insitition established in the following decade to which patients from the existing facility in Ilha do Governador were transferred. The West Zone location was chosen for it’s isolation from Rio’s urban center and lush forest and green areas, as the medical thinking of the time was that psychiatric patients should have contact with nature. The institution built houses for workers on the enormous grounds, which was renamed Colônia Juliano Moreira in 1935 after the recently deceased doctor known for his humanized treatment of patients.

Famed throughout the mid-20th century for its mental health facilities, the institution then went into decline. In the 1980s, communities started growing around the traditional workers’ houses and the area’s first favelas were established. Today, Colônia Juliano Moreira is home to 11 communities, around 30,000 people, and the institution–which along with the land, was handed over to the City to manage in 1996–operates in a significantly reduced capacity.

Recent years have brought a series of confusing government interventions to the area. Though federal Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) works were programmed for 2007-2010 with a budget of over R$105 million, they were stalled and have now been assigned as part of the municipal Morar Carioca favela upgrading program. Mayor Eduardo Paes declared the area officially a neighborhood in 2011, dividing it into four “sectors.” These divisions have been repeatedly revised and updated, the latest in January this year dividing the region into ten “areas.” E-Colônia members believe the divisions are to impose specific policies in specific areas, for example construction rules, and fragment the collective mobilization of the neighborhood.

TransOlímpica to pass through Colônia

E-Colônia is primarily concerned with preserving the Colônia’s Atlantic Forest environmental characteristics. They have however become a spokespeople for the neighborhood’s broader concerns since discovering the planned change in the TranOlímpica BRT highway’s route. They found out that it is now to pass through Colônia from topographers conducting research in the area. The highway will pass through Jacarepaguá to connect the Olympic Park in Barra da Tijuca with another Olympic site in Deodoro, North Zone. The change in route is supposedly to reduce the number of evictions necessary. However, it is set to pass over communities in Colônia and the area’s semi-protected forest areas. The projected new route also passes 100 meters away from the new Elderly Village of public sheltered accommodation for elderly psychiatric patients.

E-Colônia is primarily concerned with preserving the Colônia’s Atlantic Forest environmental characteristics. They have however become a spokespeople for the neighborhood’s broader concerns since discovering the planned change in the TranOlímpica BRT highway’s route. They found out that it is now to pass through Colônia from topographers conducting research in the area. The highway will pass through Jacarepaguá to connect the Olympic Park in Barra da Tijuca with another Olympic site in Deodoro, North Zone. The change in route is supposedly to reduce the number of evictions necessary. However, it is set to pass over communities in Colônia and the area’s semi-protected forest areas. The projected new route also passes 100 meters away from the new Elderly Village of public sheltered accommodation for elderly psychiatric patients.

Residents, many of which can trace their families back to the psychiatric institution’s beginnings, are concerned for their history and homes, but principally for the ecological damage the expressway would cause. Catia Loreira, 33, born and raised in Colônia, says: “We want to tell people about the environmental area we have here and the damage the highway would cause.”

Abandoned Public Works

On January 25th, 2010, then President Lula, Rio’s state Governer Sérgio Cabral and Mayor Eduardo Paes inaugurated the first completed works of the PAC in Colônia Juliano Moreira. These included paved streets, playground and football pitch, plus the announcement of a Child Development Space to be built. The City’s official announcement outlined the continuation of the project in Colônia to include the upgrading of all the favelas, paving of roads, drainage of rivers, construction of an Elderly Village, restoration of the historic area, new museum, land titling, social projects and the construction of 600 public housing units: “These interventions aim to transform Colônia Juliano Moreira into a new neighborhood, preserving its green space.”

On January 25th, 2010, then President Lula, Rio’s state Governer Sérgio Cabral and Mayor Eduardo Paes inaugurated the first completed works of the PAC in Colônia Juliano Moreira. These included paved streets, playground and football pitch, plus the announcement of a Child Development Space to be built. The City’s official announcement outlined the continuation of the project in Colônia to include the upgrading of all the favelas, paving of roads, drainage of rivers, construction of an Elderly Village, restoration of the historic area, new museum, land titling, social projects and the construction of 600 public housing units: “These interventions aim to transform Colônia Juliano Moreira into a new neighborhood, preserving its green space.”

The Child Development Space was inaugurated on November 7th, 2011 by Mayor Eduardo Paes alongside the Municipal secretaries of education, housing, civil office and chief of staff. Paes highlighted how the family education and activity center for 250 children and other works in Colônia were being made possible through the municipal favela upgrading program Morar Carioca. He said: “With this work in Colônia Juliano Moreira, we are recovering and preserving this fantastic historic heritage of the city and at the same time bringing dignity to people with well done, quality and sustainable works.”

In Colônia, people refer to the PAC, not Morar Carioca, which in design is a program based on community participation, yet is being used as a catch-all term for municipality-administrated works in favelas.

In Colônia, people refer to the PAC, not Morar Carioca, which in design is a program based on community participation, yet is being used as a catch-all term for municipality-administrated works in favelas.

Residents complain of abandoned and poor quality works. Juliana says: “Waste, garbage, insects and Dengue mosquitos are accumulating in all the locations where the City has done work or set up a building site. The streets are full of holes that they’ve made. For example, they throw rubbish in an area destined to be garden. What was supposed to be a garden project, they now leave waste and stagnant water.” She also cites works on the drains system from Rua Sampaia Correo and the year-old Elderly Village directs sewage into the Colônia river.

Paes claims that the works are sustainable and bring dignity to Colônia residents can most clearly, and sadly, be refuted with the case of Dona Rita Maria Barbosa, a 57-year-old community agro-ecologist who was forcibly evicted by City representatives and her home and organic fruit and vegetable garden destroyed in August of last year. Today the site is boarded up.

Compulsory Treatment of Crack Addicts in Colônia

In March 2011, the Paes administration passed a statute allowing the forced internment of children and teenagers for drug treatment. The controversial program, an attempt to deal with Rio’s growing crack and child homelessness problems, introduced operations rounding up young addicts in the city’s cracolândias (areas occupied by crack users) and taking them to drug treatment centers.

Then, in October of last year, Mayor Eduardo Paes revealed the planned extension of the policy to include forced internment of adult drug addicts, and plans to create a further 600 drug treatment spaces at a yet-to-be decided location. The first operation took place on February 19th on the edge of Avenida Brasil in Complexo da Maré with 29 addicts involuntarily hospitalized for treatment.

Meanwhile in Colônia, residents report that the City has ordered the suspension of three of the psychiatric insitution’s clinics’ activities, leaving patients without service or explanation. Workers at the clinics report that they’ve been told to stop services, relaying that the locale will be used to incorporate the compulsory treatment of drug addicts.

Meanwhile in Colônia, residents report that the City has ordered the suspension of three of the psychiatric insitution’s clinics’ activities, leaving patients without service or explanation. Workers at the clinics report that they’ve been told to stop services, relaying that the locale will be used to incorporate the compulsory treatment of drug addicts.

Residents argue that with crumbling, open plan buildings at the old heart of neighborhood, the psychiatric institution doesn’t have the necessary structure to provide secure treatment for drug addicts who have been brought against their will.

Speaking at the public debate on compulsory internment of drug addicts held by councilman Renato Cinco, who is pushing for a parlimentary inquiry into the policy, E-Colônia leader and Colônia resident of 22 years, Aline Santos called for an investigation into the situation. “When we push, when the media pushes, for an answer, he denies it. There’s a lack of transparency. It reinforces the idea that they are removing drug users from Avenida Brasil ahead of the mega-events and putting them in areas hidden from society. Colônia really is an area that’s hidden from society.”

The Future of Colônia Juliano Moreira

“This place is very beautiful, close the Pedra Branca forest,” enthused then Municipal Housing Secretary, Jorge Bittar, at the 2011 inauguration of the Child Development Space in Colônia. Speaking of future works in the community, he said, “We will value the historic and environmental aspects and above all, the quality of life of all that reside in or visit Colônia.”

This is not how the authorities’ intentions in Colônia are currently being interpreted on the ground. Juliana, who cannot finish the already constructed second floor of her home because of a construction ban, says: “It’s as if [Colônia] is a big hole and they’re chucking everything in to hide it from the city.”

This is not how the authorities’ intentions in Colônia are currently being interpreted on the ground. Juliana, who cannot finish the already constructed second floor of her home because of a construction ban, says: “It’s as if [Colônia] is a big hole and they’re chucking everything in to hide it from the city.”

As well as organizing the meeting on March 22nd, E-Colônia has been active holding a protest march in the community, have called on local media, and forged solidarity partnerships with other social movements. Their demands are quite simply information and the opportunity to participate in decisions about their unique neighborhood.

Aline, the most vocal and impassioned member of the group, says: “The community has to be informed and what we are demanding is in the law: share the information before it’s implemented. At the moment they’re planning something, they need to take this information and share it with not just the community but society as a whole.”