On Thursday night, June 20, at least 300,000 Cariocas (Rio residents) filled Avenida Presidente Vargas and walked from Candelária to the Prefeitura (the city government building), while at least 700,000 other Brazilians across the country demonstrated on the streets of 75 different cities. Put another way, roughly one in every 200 Brazilians came to the streets to express their indignation.

The protests, which continue to grow and spread across Brazil, have long ceased being about a 20 cent bus fare rise. As 23-year-old student Rodnei Pascoal, a resident of Taquara, said, “I think it was time for the people to demonstrate against the injustices that we have suffered […] it’s not only about 20 cents, the 20 cents was the last straw.”

Although their presence has been underreported, Rio de Janeiro’s favela residents have been participating actively in the demonstrations.

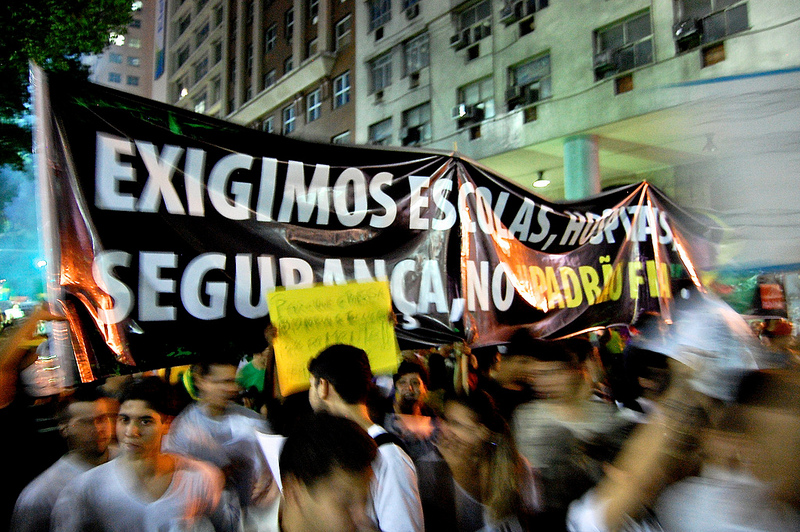

Wirson, a 61-year-old resident of Cantagalo, said, “We are going to fight for us, for what we want. The city we want. The country we want…[for] work, our rights, and real citizenship rights.” Wirson’s words reflect the general sentiment of Thursday’s demonstration. People held signs covering a multitude of social issues plaguing Brazil: health, education, PEC 37–a bill that would make it illegal to conduct criminal investigations into Brazilian officials–forced evictions, exorbitant World Cup spending, low salaries and a rising cost of living. Marching with the 300,000 in Rio, one sensed the strong indignation–a feeling that underlies all the demonstrations across Brazil, the feeling that despite the nation’s recent economic success, people are suffering from the government’s failure to provide for their most basic needs.

Thursday afternoon, before the main demonstration at 5pm, thousands gathered in Saint Francisco de Paula Square in downtown Rio. There was a festive feeling throughout–live music playing, and people chanting and making posters–creating an atmosphere of hope. A large group of favela-based community leaders met together to prepare for the protest. Everyone I spoke with that afternoon expressed one consistent demand: a government that works for its people.

Maurício Braga, a 60-year-old member of the Movimento Nacional de Luta pela Moradia (National Movement for the Struggle for Housing), said, “I can say with some certainty, if [the government of Brazil] had heard the voices of the Brazilian population, we would not have the World Cup in Brazil because it is clear today that these projects are going to cost Brazilian society a lot.” Projects such as the Bus Rapid Transit lines, Porto Maravilha and the Olympic Park are costing Brazilian society a lot more than just money, displacing thousands of families in Rio’s favela communities.

When asked about the favelas and the protests, Maurício said, “This movement, which actually was initiated by young people fighting for free transport, ended up awakening and articulating all the segments and social organizations that are also fighting (for basic rights).” While many are describing the demonstrations as a student or middle class movement, many other organizations and parts of Brazilian society have been in the fight against injustice, including the residents of Rio’s favela communities, for a long time. And they have embraced the recent protests as their own.

Moreover, the indignation manifesting in the streets of Rio is one that also expresses a general mistrust in the Brazilian government to resolve the most pressing issues facing Cariocas today, and a sense of being together. As Lenilda Rodrigues, a resident of Indiana, said, “We are all in the same fight. All of us here are from various communities, various cities, various states […] we have the right to live well, and to a good life, and this is what we work for. One helps the other; one adopts the cause of the other. The people see inequality where they should have support [from the government].” Lenilda distrusts the government to the point of insisting she will never to vote again, even passing along this sentiment to her 18 year old daughter, as well as her passion for direct civic engagement.

Maria do Socorro, a member of the Indiana Residents’ Association fighting the evictions, said, “I think it’s very important that the [favelas] are here, like Morro da Providência and Santa Marta, because our fight cannot stay only within the community.” She went on, “My fight is not only about the community. [It’s about] buses, health, education, racism, everything.”

The protests express a general indignation on the part of Brazilians–of all walks of life–towards the current state of their country. And the overwhelming message of Thursday night’s demonstration was that many of Rio’s social movements, which include the movement against forced evictions, are now working together to fight for a better Brazil.