Students occupying public high schools across Rio state have faced increasing levels of violence and harassment since May 6 from groups of students against the movement.

The occupation at the Mendes de Moraes school in Ilha do Governador, the first school to be occupied in the current wave of student protests taking place across Brazil, has been forced to disband. Students there were subject to consecutive attacks beginning on May 6 and occurring daily between May 9 and 13.

Alan, an 18 year-old alumnus of Mendes, said the students occupying the school building had felt increasingly intimidated by the “de-occupy” group’s efforts to enter the premises. Describing the attacks occurring on May 10, Alan said students “jumped over the walls and broke our padlocks.”

“We barricaded ourselves in our security room, but they were very strong and they wanted to reach us at any cost,” he said. “Part of the door broke and cut one student. In all the confusion, people only knew how to cry, how to keep trying to barricade the door.

“Punches were thrown and we really didn’t know what was going to happen. We decided for our own safety to de-occupy, for all we knew they could have lynched us in that moment.”

Teachers and students report that longer and more violent attacks occurred on May 13, claiming the “de-occupy” group threw bricks, glass bottles and bombs into the school.

“Every time we re-occupied, the threat of violence became greater,” said Alan. Students from Mendes reached a final decision to de-occupy and instead support other threatened schools on the evening of May 16.

Students reported that Military Police stood by outside the school while the attacks were carried out, and rather than protecting them, the police used their presence to prevent protesting students from re-entering the empty school. Teachers at Mendes were appalled by the lack of police intervention to prevent students from physical harm.

“The situation in Mendes had become unsustainable,” said Adno Soares Ferreira Jr, a teacher at the school who witnessed the attacks on May 13.

“The Department of Education was terrorizing pupils and parents, saying they would miss the whole school year and instructing police not to intervene during increasingly violent attacks on the students,” he said.

Threats from “de-occupy” groups

Mendes is one of many schools to be recently threatened by de-occupy groups. Between May 9 and 13, there were also calls on social media for support for occupied schools in Bangu in the West Zone and Centro that were facing threats from de-occupy groups.

Leonardo, a student at Amaro Cavalcante school in Largo do Machado in the South Zone, said he wasn’t surprised that schools outside the South Zone were facing more violent threats than his own.

“Mendes was always going to receive more threats purely by being the first to occupy,” Leonardo argued. “It’s a school facing very precarious conditions and with a huge lack of materials. But it’s also a school in the outskirts of Rio, with comparatively little visibility which makes it much easier to attack.”

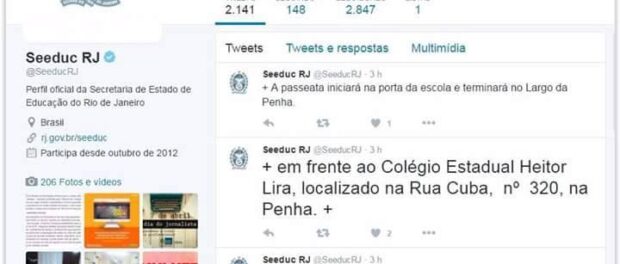

Amaro Cavalcante is one of many other schools to face opposition, with organized Facebook groups against the occupation. De-occupy groups have begun formally organizing and gathering steam since Rio’s State Education Secretariat (SEEDUC) sent a tweet encouraging students to organize their own actions several weeks ago.

The de-occupy movement is proving less popular: Desocupa Mendes’ Facebook page has 2,500 “likes” while Ocupa Mendes has 14,000. Nonetheless, some students have attributed an increase in threats and violence to SEEDUC’s deleted tweet (pictured above).

Students at Amaro Cavalcante have opened dialogue with those against the occupations, who claim that the conditions students are protesting against do not apply to their school.

“The occupation isn’t just something for me,” said Leonardo, who is in his final year at Amaro Cavalcante. “Every time we speak to students against the movement, they leave on our side. They understand that we are all fighting for the same thing, for better quality education.”

Government negotiations

Despite the breakdown in dialogue between students for and against the occupations, Rio’s state government announced results from the first successful negotiations with occupying students.

High school students will receive a mock college entrance exam (Enem) and parents and teachers will have more say over electing a school director. The recently introduced evaluation system, SAERJ, will finish at the end of this school year to align with budget cuts, and students will be able to top up their free bus cards on a monthly basis rather than weekly.

Leonardo voiced skepticism regarding the announcement, calling SAERJ a “fictitious measure used to produce statistics rather than a quality education.” He felt the changes to the bus card would make little difference to students’ lives, and questioned how any state government could produce an accurate replica of the national, federal Enem examination.

He also said that the directors chosen and imposed by governments are frequently absent. “I’ve never seen the guy,” he said. “I couldn’t tell you if he’s black or white, yet he’s my school director. This was an important point for students and for teachers.”

Negotiations have not yet touched on initial points raised by students first occupying: lack of infrastructure and repairs plus cuts to existing infrastructure, lack of access to resources, arbitrary firings of personnel making school functionality more difficult.

“If they think they can resolve these smaller problems and then we’ll leave, it’s not going to happen,” said Leonardo, smirking. “These occupations exist because real change needs to come. We want the government to know that we will closely monitor what’s going on.”