Since 2016, 710 children and adolescents have been shot in Greater Rio—an average of nearly two young victims per week. According to a February 2025 report by the Fogo Cruzado Institute, which collects data on armed violence, this figure reflects the increase in police operations involving children and adolescents as victims. State security agents were involved in 36% of shootings, up from 28% in 2017. It is no coincidence that a record number of children were hit by stray bullets last year: 26 cases.

Of the 268 children who died violently since 2016, 59% were killed by stray bullets, 26% during police operations, and 10% in clashes between criminal gangs. Despite the gravity of these incidents, 60% of the cases remain without a concluded investigation, according to another report by the Rio de Janeiro Public Defender’s Office.

The stories behind these statistics reveal the urgent need for policies that protect the lives of children like Kamila Vitória, a 12-year-old killed in 2024 while playing in Del Castilho, in Rio’s North Zone, and Diego, a four-year-old shot that same year alongside his parents in Paty do Alferes, in the state’s interior. The city government’s removal of the memorial at Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon—built in honor of children killed by armed violence—symbolizes the tension between erasing pain and confronting it.

Fogo Cruzado Institute’s 2024 Annual Report reveals the paradox of armed violence in Rio de Janeiro. While the total number of shootings fell to 2,535—the lowest in eight years—public security actions have become increasingly linked to armed confrontations in the city. In 2024, 36% of all shootings occurred during police operations, compared to 28% in 2017.

In 2024, 26 cases of children shot by firearms were recorded in the Metropolitan Region—16 of them hit by stray bullets. Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region had the highest number of such cases (13), followed by the city’s West Zone (6) and North Zone (5). That same year, of the total number of people hit by stray bullets in the city of Rio, the North Zone accounted for 48% (51 cases), surpassing the Baixada Fluminense (24) and the West Zone (20). The main causes of shootings included clashes between gangs and militias (11 cases), targeted attacks on civilians (7), homicides (5), and police operations (4).

Despite 2024 recording the lowest incidence of shootings in the last eight years, the Greater Rio Metropolitan Region saw 32 people shot in just the first two months of 2025. This was the highest number for that period since 2021—72% of the cases occurred during police operations.

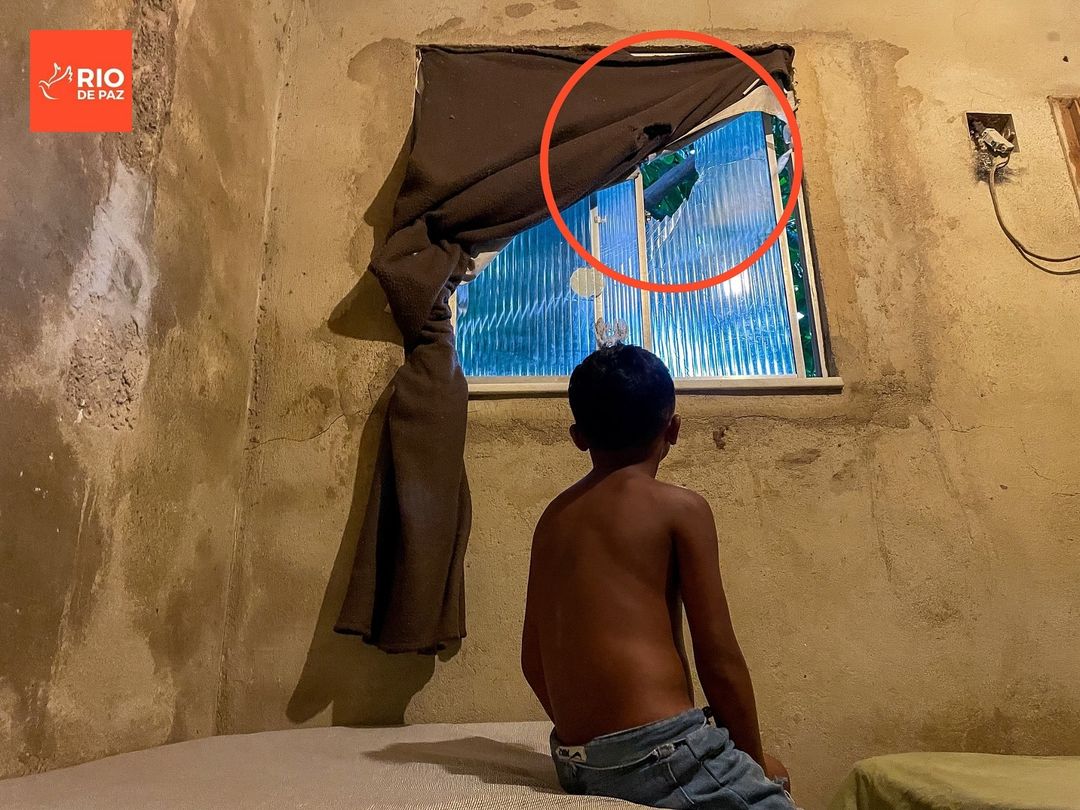

Furthermore, in early 2025, incidents involving stray bullets increased by 58% compared to the same period in 2024. Among the victims were a 17-year-old shot inside his home in the North Zone’s Complexo do Chapadão; ten-year-old José Murilo, hit in Complexo do Salgueiro, in São Gonçalo; and eleven-year-old Pedro Henrique, shot in the West Zone neighborhood of Realengo. This ongoing social tragedy reveals the persistent risk of violent death for children and youth in Rio’s favelas and peripheral areas. According to Antônio Carlos Costa, founder of the NGO Rio de Paz (Peaceful Rio), the solution is far from simple.

“No single measure will solve the problem of violence in the state of Rio. We need a package. And this package involves tackling social inequality, implementing public policies in the favelas, reforming and valuing the police, rethinking the war on drugs. In other words, we need that [kind of] State that enters the favelas truly committed—bringing leisure spaces, quality public education, healthcare, employment opportunities, which today do not exist. We’ve been doing the same things for decades and expecting different results.” — Antônio Carlos Costa

For 18 years, Rio de Paz has worked to defend human rights: denouncing violations, promoting justice, and strengthening solidarity. Its trajectory has been marked by actions in defense of democracy, remembrance of victims of State violence, support for vulnerable communities, and advocacy for victims of police violence.

“Our movement began in 2007 when we saw homicide rates were extremely high and felt we had to do something, because it was outrageous. Reducing homicides is one of the pillars of our organization. Since then, we’ve been demanding that the state and federal governments create a public security plan for Rio, with clear protocols for police operations in favelas, concrete goals, and timelines to reduce homicides and combat the trafficking of guns and ammunition in Rio de Janeiro—since the state doesn’t manufacture them, but knows there’s an arsenal in the hands of criminals.” — Antônio Carlos Costa

‘Police Operations Need to Account for School Hours and Spare Areas Around Educational Spaces’

In 2020, the Brazilian Supreme Court (STF) began hearing ADPF 635 (Claim of Non-Compliance with a Fundamental Precept No. 635), better known as the ADPF of the Favelas. The case seeks to rein in the rise in police violence, which skyrocketed during the pandemic, aiming to guarantee the lives of favela residents who were required to stay home during coronavirus lockdowns but were, by staying home, placed directly in the line of fire during violent police operations.

The Court’s ruling required that police operations in favelas be duly justified, planned and monitored by the Public Prosecutor’s Office. In the first few months, the results were positive—there was a 23% reduction in shootings and a 26% reduction in the number of gunshot victims. Additionally, the number of people shot decreased by 45% and the number of police violence victims decreased by 57%.

Data from the Fogo Cruzado Institute proves the effectiveness of the ruling. Before the ADPF ruling was implemented, 2,881 people were shot in the Greater Rio Metropolitan Region in 2023. After the ruling’s implementation, in 2024, this figure fell by 45%, down to 1,566 cases. In addition, the number of victims struck by stray bullets during police operations fell by half, from 62 to 31 persons, and the number of State security apparatus agents shot while on duty fell by 60%, from 40 to 16 officers.

However, in 2025, the Brazilian Supreme Court relaxed some aspects of the ADPF ruling, reigniting fears of setbacks. This relaxation extended the deadline for installing cameras in police vehicles to 180 days and lifted restrictions on the use of helicopters and police operations near schools and hospitals—except in circumstances deemed disproportionate.

According to Carlos Nhanga, an analyst at the Fogo Cruzado Institute, while Rio Governor Cláudio Castro celebrated the changes, human rights organizations warned of the risk of increased police abuse and especially criticized the lack of clear criteria for removing officers involved in extrajudicial killings.

“Many child victims are hit during poorly planned police operations, often carried out at particularly sensitive times and locations—like near schools, during drop-off or pick-up times. Police planning needs to account for school hours and spare areas around educational spaces. The police also need proper resources to improve investigation rates. Most cases involving children being shot end in complete impunity.” — Carlos Nhanga

Moreover, decisions at both the state and city level are moving in the opposite direction of addressing armed violence against children. While the state government presented Decree No. 48,138, its public security plan, with no specific measures to protect children and adolescents, the Rio de Janeiro City Council approved, in a first-round vote (43 to 7), Bill 23-A/2018, which authorizes the arming of the Municipal Guard.

The Federal Prosecutor’s Office and the Rio de Janeiro Public Defender’s Office were critical of the bill, warning of the risks of increased violence and a repetition of well-known failures.

“As long as lethality is seen as a measure of police efficiency, investigations will continue to take a backseat. A security policy that prioritizes investigation and intelligence must be implemented, including investment in technical training for investigative teams, strengthening internal affairs departments, and increasing transparency in investigative procedures. Without qualified and systematized information, planning effective actions will remain compromised.” — Carlos Nhanga

For this article, RioOnWatch contacted the Governor’s Office and the Secretariat of Public Security to inquire about the existence of other public policies aimed at protecting children, since Decree No. 48,138 includes no specific provisions for this purpose. As of publication, no response has been received.

Organizing Efforts Achieved Symbolic Victory, Yet Construction Lags on Official Memorial for Victims

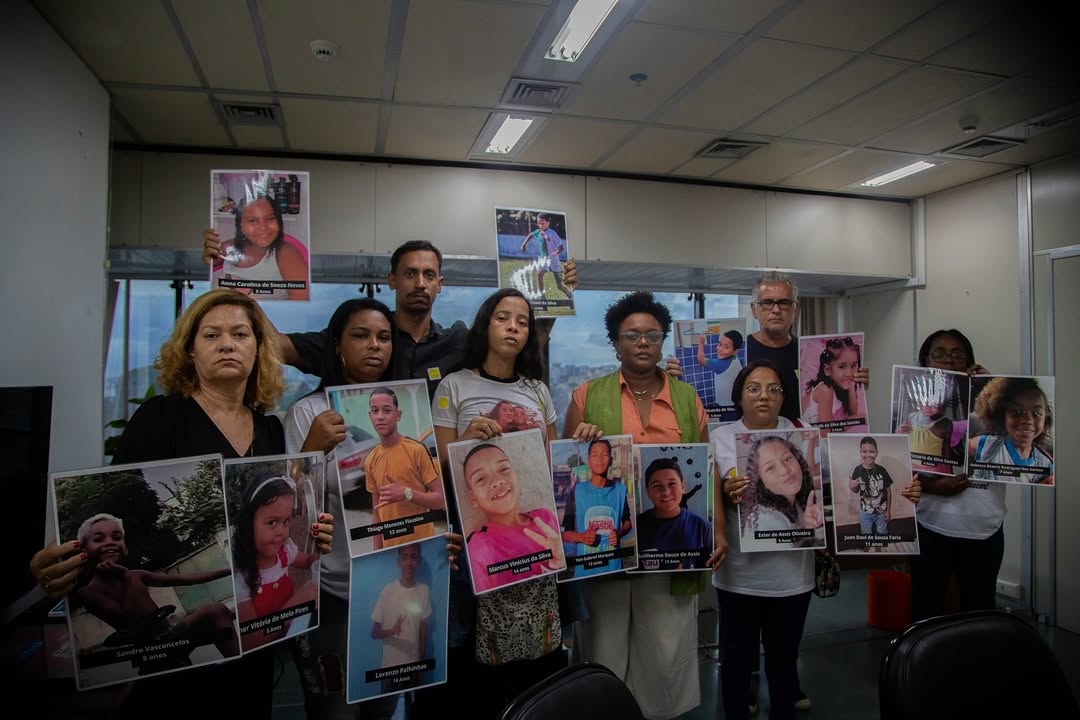

On December 28, 2024, Rio de Paz held a protest at the Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon against the killing of children by stray bullets, replacing the plaques of a local memorial with 49 photos of victims. The action sought to pressure public officials and raise societal awareness.

The following day, however, Rio Mayor Eduardo Paes ordered the removal of the photos, claiming that Rio de Paz had not obtained official authorization—despite tributes to fallen police officers remaining in the same location. Paes had previously criticized the memorial to the children in the 2022 documentary The Aesthetic of the Struggle, despite claiming to recognize its relevance.

The mayor’s decision outraged victims’ family members and activists, as the memorial had existed since 2015 without issue from City Hall. In response, Rio de Paz organized a new event on January 4, 2025, bringing together family members and volunteers who displayed photos of the children at the former memorial site.

Following mobilization efforts, a January 9 meeting with the City’s Secretary of Environment and Climate, Tainá de Paula, discussed the creation of an official memorial, allowing for the temporary display of the images.

The pressure led to a new meeting on January 13, which officially authorized the reinstallation of the photos and promised the future construction of a permanent memorial. The mayor apologized for the suffering caused and acknowledged the importance of the tribute to the victims’ families. The images were returned to the site on January 15, marking a symbolic victory in the fight for memory and justice.

“We had a meeting with the mayor on February 13. He acknowledged his mistake, apologized, and promised to create a memorial. On February 15—two days later—we returned with the children’s families to the mural, where we reinstalled the photos. It was agreed at the meeting that professionals from the City’s heritage department would present project proposals for us and the mothers to review. Everything would be done jointly. However, we have yet to receive any updates. We keep following up, but the information we’ve been given is that the projects are still being developed. The location is also yet to be determined. Our condition is that the photos will only be removed once the memorial is built—something the mayor agreed to. It’s important to note that the entire process with City Hall has been coordinated by Councilwoman Tainá de Paula, with whom we remain in constant contact.” — Antônio Carlos Costa

RioOnWatch reached out to the Mayor’s Office and the Secretariat of Public Security to request information about the construction of the memorial—including its location, timeline, and design—as well as the municipal public security plan and the positions of both the mayor and the secretary on arming the Municipal Guard. However, no response has been received to date.

“There is no way to predict the future, but the trend is that, with an additional armed force, we will have more shootings. The city government plays an essential role in urban planning, which is part of a broader public security plan. It also has the potential to generate data about the city that, if public security were jointly planned by all government entities with civil society participation, could be of great value. Unfortunately, this is not our reality today.” — Carlos Nhanga

About the author: Felipe Migliani has a degree in journalism from Unicarioca with a focus on investigative journalism. Working as an independent freelance reporter at Meia Hora and Estadão newspapers, he also collaborates with the Coletivo Engenhos de Histórias, which investigates and recovers history and memories from the Grande Méier region, and with PerifaConnection.